Greening as a pathway to resilience in urban areas

Edited on

03 June 2022Leafy places in cities can greatly improve health and happiness. But here’s the thing: green isn’t always good for everyone.

Most people now agree that green is good for health and resilience. Greening urban areas and connecting them to water, or ’blue’ areas, is high on the agenda in most towns and cities. Yet, says URBACT Programme Expert Iván Tosics, even this seemingly self-evident issue is not without contradictions. In this article, he looks beyond the general “green is good” statement and finds a more nuanced picture.

It has been said many times, almost to the point of banality, that during Covid times, the demand for outdoor activites grew dramatically, leading to a marked increase in the use of parks and outdoor spaces. We all saw this in our cities in Europe. However, this did not necessarily happen to the same extent everywhere in the world. There is an interesting website, based on Google data, showing how the number of visitors to parks and outdoor spaces(link is external) has changed compared to the selected baseline period, January 2020. Although it is not easy to interpret the data due to factors such as seasonal differences between North and South, we can hypothesise that in Europe and the global North, green areas were able to meet the increase in demand more easily, being generally more secure and better maintained than those in many parts of the global South.

There are many good summaries about the immediate, easy-to-reach interventions by cities as a reaction to Covid – see for example my article on temporary interventions(link is external) in the use of public spaces, such as closing streets and creating pop-up bike lanes, or encouraging street play. Key questions discussed in this article are: what kind of tactical interventions into greening are observable? And how can these be turned into long-term, strategic programmes, avoiding potential pitfalls?

Many people think that all greening efforts are good for the wellbeing of citizens in general, and their health in particular. However, it is necessary to go beyond this cliché, understanding the different ways to implement the greening of cities, highlighting the efforts made to achieve synergy with other aspects of sustainable and resilient development, and calling attention to potential unwanted externalities of greening projects – among which the most important is the potential increase in socio-spatial differentiation through gentrification.

Types and benefits of green places

Owen Douglas, of the Eastern and Midland Regional Assembly in Ireland, listed the benefits of green spaces(link is external) in his presentation at the URBACT Health&Greenspace Academy in December 2020. These include: enabling physical activities; improving mental well-being; supporting social interactions; and reducing environmental risks of air pollution and extreme weather events.

Green infrastructure planning can do a lot to mitigate stressful city life in compact cities, with strategically planned networks of natural and semi-natural areas, and creating new green and ‘blue’ spaces – areas of water. To achieve that, green infrastructure planning has to be multifunctional, including a diversity of green elements, such as: large natural areas as hubs; forests and parks as green parcels; smaller private gardens, playgrounds, roadside greenery, or green roofs as individual elements; corridors connecting the hubs, parcels and elements; and finally land use buffers, as transition areas, separating dense urban spaces from the suburbs.

In another presentation at the December 2020 URBACT Health&Greenspace Academy, Eduarda Marques da Costa, of the University of London, listed different types of green space interventions(link is external), from overarching development of new neighbourhoods through regeneration of residential areas and brownfield areas, including smaller-scale improvements to public spaces and support for urban gardening.

Innovative greening examples

Let us see now a few examples of the different types of greening interventions and their potential consequences.

Certain European cities have conducted large projects of strategic importance to improve sustainability and resilience.

|

Barcelona, Parc de les Glories (photo by Iván Tosics, November 2021) |

Barcelona (ES) provides an excellent example, with its efforts to renaturalise the densely built-up city. One of the emblematic projects is the rebuilding of the Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes: besides the demolition of the elevated roundabout for cars and the building of a new High Speed Train station, a large new park is being erected under the motto of renaturalisation(link is external).

Utrecht (NL) has put re-canalisation(link is external) into the core of its urban development strategy. Forty years after the historic mistake of converting the canal that encircled Utrecht’s old town into a 12-lane motorway, in 2020, the city opened the canal back up again. The restoration of the waterway was the central piece of the 2002 referendum in which residents voted for a city-centre master plan with the aim to replace roads with water. With the reopening of the Catharijnesingel, Utrecht’s inner city is again surrounded by water and greenery rather than asphalt and car traffic.

Paris (FR) has undergone large changes since the election of Mayor Anne Hidalgo in 2014. One of the key elements of the changes towards more sustainable urban development is the permanent pedestrianisation(link is external) of roads along the river Seine and certain canals, which made the access to waterfront areas much easier.

Another pathway towards more sustainability is to renovate, animate, and improve the safety of existing green areas. A prime example of this is the case of Bryant park in New York(link is external) (US). This was one of the no-go areas of the city, getting the nickname 'Needle Park' in the 1970s because of the large number of drug addicts who frequented it. Changes started in 1988 with an extensive renovation of the park, including radical physical restructuring of the area, making the green space attractive, transparent and lively, clearing areas to let in light, installing many moveable chairs, and creating coffee places. The park has been transformed from an insecure to a lovely space.

|

Breda, Valkenberg Park |

A similar story is the redesign of the Valkenberg Park in Breda(link is external) (NL) to improve safety, presented at the URBACT Health&Greenspace Academy in October 2021 by David Louwerse, project manager, Municipality of Tilburg.

The most common greening interventions in European cities are smaller interventions, such as creating urban gardens, or greening streets and rooftops. An article by Tamás Kállay, Lead Expert of the URBACT Health&Greenspace network, gives a good overview of such initiatives. He mentiones Tartu (EE), where “meadow boxes were placed on the road. A beach bar was opened, and the street section accommodated also an outdoor reading room, a market, picnic tables, an outdoor cinema, and various programs”. Another example from the Health&Greenspace network is Poznań (PL), where “as part of a pilot activity natural playgrounds were created in the yards of several kindergartens providing direct contact with nature and supporting creative play”.

Such examples demonstrate that “… small green space interventions, both physical changes and social activities can trigger a massive change and lead to larger actions promoting positive health outcomes.” This conclusion is further supported by another URBACT article, arguing for the importance of walking, not only in shopping streets, but also across all neighbourhoods – including ‘consumption-free’ areas.

Besides punctual interventions, many cities aim to ensure fair distribution of green across the whole city and to connect green areas into networks. Poznań is good example for the latter, aiming to protect the green belt(link is external) around the city from real estate development and urban sprawl, while also increasing forest cover within the city boundaries and preserving and improving existing parks and green spaces.

Changing people's mindset and reorganising the structure of local government

Hegyvidék, district 12 of Budapest, Lead Partner of Health&Greenspace, provides innovative examples of public spaces being improved and used more frequently thanks to new ideas, rather than concrete physical greening interventions. In order to change people's mindset, the “…municipality identified ‘green prescription’ as an appropriate tool for linking cardiac rehabilitation with the Active Hegyvidék program. Green prescription is a written advice of a health professional to a patient to participate in some sort of nature-based activity.”

Hegyvidék is also pioneering an institutional restructuring of the the municipality, creating a so-called Green office. Changes can also be achieved without reorganising the municipality. For example, the URBACT network UrbSecurity presents an Urban Planning Game where Leiria’s municipal technicians develop step-by-step new approaches to increase the security of public spaces in the city. Cities can also use nudging techniques to influence behaviour, as many of the publications of Pieter Raymaekers(link is external) (Leuven) show.

The positive effects of greening and their link to urban planning

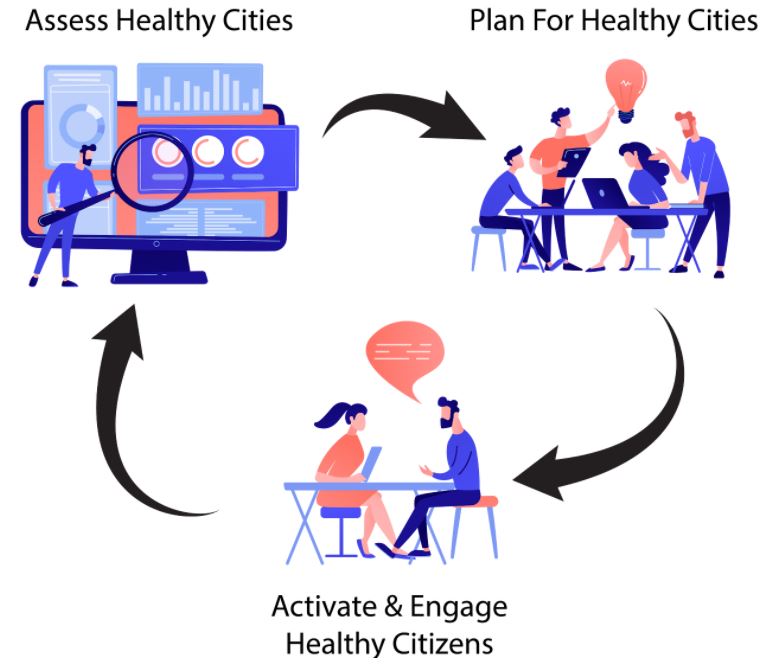

Another URBACT network, Healthy Cities, focuses on including health considerations systematically into urban planning. To make this easier, a new tool has been developed, enabling users to quickly assess the health impact of their whole urban plan, and see how small adjustments could make a big difference to the lives of local people. This Healthy Cities Generator(link is external) is a practical planning tool designed to give actionable indicators for anyone looking to integrate health into planning. It is based on a systematic review of scientific peer-reviewed publications linking urban determinants and their impact on health, through which the tool automatically calculates the health impact of urban planning actions.

Another URBACT network, Healthy Cities, focuses on including health considerations systematically into urban planning. To make this easier, a new tool has been developed, enabling users to quickly assess the health impact of their whole urban plan, and see how small adjustments could make a big difference to the lives of local people. This Healthy Cities Generator(link is external) is a practical planning tool designed to give actionable indicators for anyone looking to integrate health into planning. It is based on a systematic review of scientific peer-reviewed publications linking urban determinants and their impact on health, through which the tool automatically calculates the health impact of urban planning actions.

The integration of green considerations into planning can best be achieved by regulating the access to green areas at metropolitan level – this proved to be very useful during the Covid pandemic in those urban areas, where metropolitan coordination was strong enough.

A word of caution: potential dangers of greening interventions

Against all good will, greening interventions can also have negative effects, if not applied in an integrated manner, without creating synergies with other aspects of development.

Greening usually goes well with sustainable urban mobility interventions. When regenerating public spaces, areas taken away from cars can give place to green elements, for example changing motorways into urban boulevards with trees, pedestrianising streets, turning parking spaces into ‘parklets’ with moveable plant pots. However, if large green developments are concentrated in peripheral areas of cities that are difficult to access by public transport, they can easily result in increased car use. In a broader sense, this is a danger in all green developments that create large spatial imbalances in cities, i.e. new green areas far away from many residents who would like to use them.

When managed in the right way, greening can have very important social advantages: it is a good tool to better involve disadvantaged groups into society. Greening can help the social involvement of the elderly and school children – see for example the OASIS project, converting schoolyards into green cooling islands in Paris(link is external). Even so, the biggest danger of greening interventions lies in their negative social externalities, through the gentrification process.

Gentrification can take various forms. The direct form is the regeneration of socially contested areas into high-quality neighbourhoods. If no parallel efforts are made to support disadvantaged groups, the outcome will be socially unacceptable: pushing out disadvantaged social groups to other parts of the city. I described this process in an earlier article, on the case of Teleki tér, Budapest (HU), comparing this one-sided, gentrifying regeneration to the more integrated approach used in the case of Helmholtz square, Berlin (DE). The latter, through ongoing social assistance, is much closer to the URBACT-supported integrated approach, despite the fact that participative planning was also applied in the Budapest case.

|  |

Budapest, Teleki square with fences around, 2015. | Berlin, Helmholtz square, 2015. |

A more common and less direct form of gentrification prevails through the increase of property values and rents in areas of improving quality of life, for example due to green interventions, which leads to the gradual displacement of people of lower socio-economic status. This well-known market mechanism can be kept under control with public regulations on rents, housing allowances and/or maintaining a substantial share of publicly owned housing. Unfortunately, such public interventions to control gentrification are rarely applied (or even considered) along with urban greening.

Greening is an essential form of environmental intervention. The principle of integrated development requires a certain balance between economic, environmental and social aspects of development. This, however, is not easy to achieve, even in cases when there is strong determination to keep the balance. The comparison of two European cities, developing new ecological areas, illustrates the difficulties, showing how overly strong insistence on high environmental standards might lead to the deterioration of social goals, if public resources are limited. If greening aspects are given preference over social protection aspects, the outcome is again gentrification, against the original will of the politicians.

|  |

Vienna, Aspern Seestadt, 2018. Source: Iván Tosics | Stockholm, Hammarby Sjöstad, 2006. Source: Iván Tosics |

This article aimed to show that greening is usually a very advantageous aspect of urban development. However, certain dilemmas and potential pitfalls must be taken into account when planning green policies and interventions. With careful procedures, including green infrastructure planning as part of an integrated vision, and measuring the green and social outcomes of all investments, these pitfalls can be avoided.

Come and meet us!

This topic will be discussed at the upcoming URBACT City Festival on 15 June 2022 in a session titled ‘Greening as pathway to urban well-being and resilience’. The session will feature good practices from three URBACT Action Planning Networks, Health&Greenspace, Healthy Cities, and UrbSecurity.

Submitted by ivan.tosics on

Submitted by ivan.tosics on