How can local groups live on after URBACT projects end?

Edited on

02 August 2022URBACT experts share three strategies for towns and cities to ensure their URBACT-sparked local participation keeps on thriving.

How do towns and cities maintain the momentum for collaborative actions and innovation created in their URBACT Local Groups (ULGs)? And what structures can be put in place to continue the ULGs’ role after URBACT projects end? Answers to these questions are crucial to consider with the end of another cycle of Action Planning Networks in the URBACT programme. Anamaria Vrabie, Eileen Crowley and Wessel Badenhorst unpack three possible strategies that each ULG can consider, stemming from their practitioner experience and a ‘fireside chat’ workshop they organised together with the URBACT Secretariat at the 2022 URBACT e-University.

Before we begin, please also consider using these additional resources, complementary to this article:

- Watch the video of our fireside chat during the 2022 URBACT e-University.

- Read the innovative governance models handout we compiled.

And now, let us share with you some of the transformative stories we have generated, witnessed and supported in the cities of Cluj-Napoca (RO), Dublin and Cork (IE). We reference these cities, not as overall good practices of innovative governance models, but rather in an effort to make things as concrete as possible, in order to understand the structure, context for emergence, and expected impact of such innovative models.

Strategy #1: formalise your ULG work into an innovation lab

In the last 15 years, there has been a strong development of innovation labs connected to public administrations. These labs can take a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on their governance model. Some operate at governmental level, some at city level. Some are mandated to specifically improve the delivery of public service, while others are tasked with prototyping solutions for emerging challenges or with the support of emerging technologies. It is useful to think about these labs as a quadruple helix living lab at the intersection with a research and development department specifically linked to a public authority. Each lab can opt to use one or more innovation methodologies, from human design thinking to behavioural insights.

For an overview of some of the most active labs at global level, this survey and this report can be useful places to start as, like ULGs, such labs convene a wide array of city stakeholders.

In Cluj-Napoca, Romania’s second largest city with a population of around 400 000 people, it was actually a failed attempt to win the title of a European Capital of Culture (ECoC) that proved a catalyst for the emergence of their innovation lab. The Cluj-Napoca Urban Innovation Unit (UIU) was a programme proposed in 2017 by Cluj Cultural Centre, an NGO comprising at the time around 60 cultural organisations and public authorities, that had prepared the ECoC strategy.

Designed in partnership with the Cluj-Napoca municipality, UIU would actually have a limited lifecycle of four-five years, in order to test what innovation approaches would be best for Cluj, while building more innovation capacity locally. If successful, the unit would be fully transferred in the local municipality. This aspect is quite relevant for towns and cities facing either a low trust in public sector actors or insufficient capacity. It allows a state or non-state actor to break the vicious circle of questioning how such a complex structure should be governed, by proposing a test-run for a limited period.

|  |

| Two pilot projects of the Urban Innovation Unit: temporary use of public space in a residential neighbourhood (left) and engaging artists to promote the use of public transportation for youth (right). | |

So, how can URBACT cities use an innovation lab structure as a vehicle for the governance and implementation of their Integrated Action Plan (IAP)?

Building on the city’s strategic documents, similar to URBACT Integrated Action Plans, the Cluj-Napoca Urban Innovation Unit (UIU) was mandated to develop pilot projects in three thematic areas: future of work, urban resilience and urban mobility. The three themes were chosen as the most relevant for emerging challenges of Cluj as a growing city. In addition, all three topics required collaborative solutions and coordination – a sole city actor such as the public administration, universities, NGOs or businesses, would find them hard to develop alone. This report describes the 15 lessons learned of the unit between 2017-2021, as well as pilot projects in each thematic area.

Early on in the existence of the Cluj-Napoca Urban Innovation Unit, their proposal for future of work, co-produced with the municipality and other key stakeholders, won the Urban Innovative Actions third call for funding, making Cluj-Napoca the first city in Eastern Europe to receive this type of European grant. This brought considerable funding and legitimacy for the lab, but narrowed down the type of pilot projects it could engage in. Nevertheless, reflecting on the emerging legacy of the unit, there are already a few tangible results:

- Concrete solutions found at city level on how to better support cultural and creative industries as an emerging sector of the local economy;

- Supporting academics to make their research usable for evidence-based policy;

- Develop new funding mechanisms that can allow community groups to work with the public administration as peers;

- Strategic partnerships and new sources of funding accessed by the city;

- Consolidated capacity for the public sector to use risk-prone methodologies such as prototyping;

- Successful transfer of tested innovation practices in a newly established department in the municipality starting from May 2022.

Thus, an innovation lab may provide a useful governance model to monitor the implementation of the URBACT IAP, being tasked to implement pilot projects together with ULG members. These pilot projects are not necessarily the comprehensive actions described in the IAP, but rather Small Scale Actions for each of them. This enables continuous engagement and a refinement of some of the big ideas planned by cities to accomplish their ambitious vision.

Strategy #2: keep a stable relationship among key city stakeholders, even if informally

In Ireland, a partnership model was initiated in the city of Cork with the aim of regenerating the city centre and reinvigorating the city space. Located in the south-west of Ireland, the city of Cork has achieved some success in taking a partnership approach to the revitalisation of its city centre in recent years. The council was rewarded for their innovative governance model in 2021 when they won the Chambers Ireland Excellence in Local Government Awards.

Cork city has a population of about 220 000 people. For a period, the city centre was losing population, and businesses in the area noticed a decline. In 2014, coinciding with a changeover in city management and the appointments of the city’s first female chief executive, a study was commissioned to kick-start transformative actions to revitalise the city centre in partnership with a wide range of stakeholders. The study made two key recommendations: create a cross-sectoral partnership to drive change; and employ a city centre coordinator – someone to act as the human face of the council, to liaise with businesses, broker relationships and facilitate action.

|

Weekend morning yoga on the board walk in Cork City centre |

The city implemented these recommendations and set up two key groups. The first consists of approximately 20 cross-sectoral representatives, including local politicians, business owners and representatives, public transport representatives, members of the Gardaí (police) and some council staff. The second group consists of members of the city council senior management team, with one manager together with an urban planner, responsible for a designated area within the city centre. Action plans and progress reports are revised each year to help realise the aims of these groups.

Change came about slowly in the city, one step at a time. Early years were focused on forming relationships, building trust and some small quick wins. The council focused mainly on showing their support for businesses by trying to animate the public space and attract people into the city centre. This was done through a variety of soft catalyst-type projects such as chalk workshops, street theatre and street art, all proving very popular and helping to animate the space and to build trust between partners.

Over time, seeing the benefits and enjoyment to be gained by public space animation, momentum started to grow with several businesses undertaking their own initiatives in this area. Examples include weekend morning yoga on the boardwalk instigated by a local coffee shop owner and the city’s infamous long table dinner which started in 2017. This was led by 12 restaurants in the city centre, feeding 420 guests in one of the city’s main thoroughfares.

|  |

Cork’s long table dinner feeding 420 guests (left) and one of the newly pedestrianised streets in the city, catering for an increase in outdoor dining (right). | |

Of course, there were stumbling blocks too, and some initiatives met with great resistance. As the famous motivational author Louise Hay says however: “resistance is the first step to change”. The City Council’s attempt to pedestrianise the main street in the city for several hours a day initially met with great opposition. In spite of this, the City Council held firm and increased their commitment to work in partnership with stakeholders to find solutions and support the continued reinvigoration of the city centre. The cross-sectoral stakeholder group met 13 times over the summer of 2019, intent on co-creating solutions to the city’s challenges. In the end, these stumbling blocks proved to bear great fruit, and working together through these challenges served to strengthen and solidify vital relationships across sectors and between stakeholders.

These strong partnerships and cross-sectoral structures in place in the city are what enabled the city to respond dynamically and quickly to the shock circumstances brought about by the pandemic.

Together, city stakeholders worked quickly to develop a response plan and to rapidly roll out activities to ensure the city centre remained an attractive and inviting space for people in the midst of the pandemic. The city quickly set in train the pedestrianisation of 17 streets within the city centre, the development of cycle lanes across the city, increasing cycle parking, creating attractive outdoor spaces with public parklets and street cleaning and supporting the development of streets for outdoor dining.

So, how can an informal partnership structure become a vehicle as a post-project structure for governance and implementation of actions in the IAP?

The post-ULG structure can aim to become a go-to forum for other emerging challenges of the city.

|

An example of some winter-proofing measures on one of the city quays |

For example, in Cork, thanks to the highly effective and innovative governance models in place for the management of the city centre, the city has been hugely successful in accessing national funding for the winter proofing of many of its newly pedestrianised streets, enabling year-round outdoor dining even in the often inclement Irish weather!

From small soft measures in the beginning to a visible increase in momentum, the city today is truly transformed. Cork showcases a city offering that competes on par with some of the most well-known and magnetic cities across Europe. This is the power of partnership and taking a collaborative approach to city development.

This approach is highly replicable and transferable even across varying contexts. Investing in a partnership model can lead to effective and positive transformations of an area, the time and commitment involved does pay off. People, partnerships and leadership are essential. Motivating factors including some soft measures, quicks wins, awards and the showcasing of inspirational good practices can all drive momentum. A clear vision, dedication and commitment however are all vital links to connect a vision to reality. An important lesson we can learn from Cork is that their partnership journey is just as important as the destination. While the city’s physical transformation is impressive, it’s the embedding of this collaborative culture and the institutionalisation of cross-sectoral governance models within the city’s practice that is truly valuable and surely heralds only the beginning of this city’s transformational journey.

Strategy #3: consider business-led governance structures such as Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)

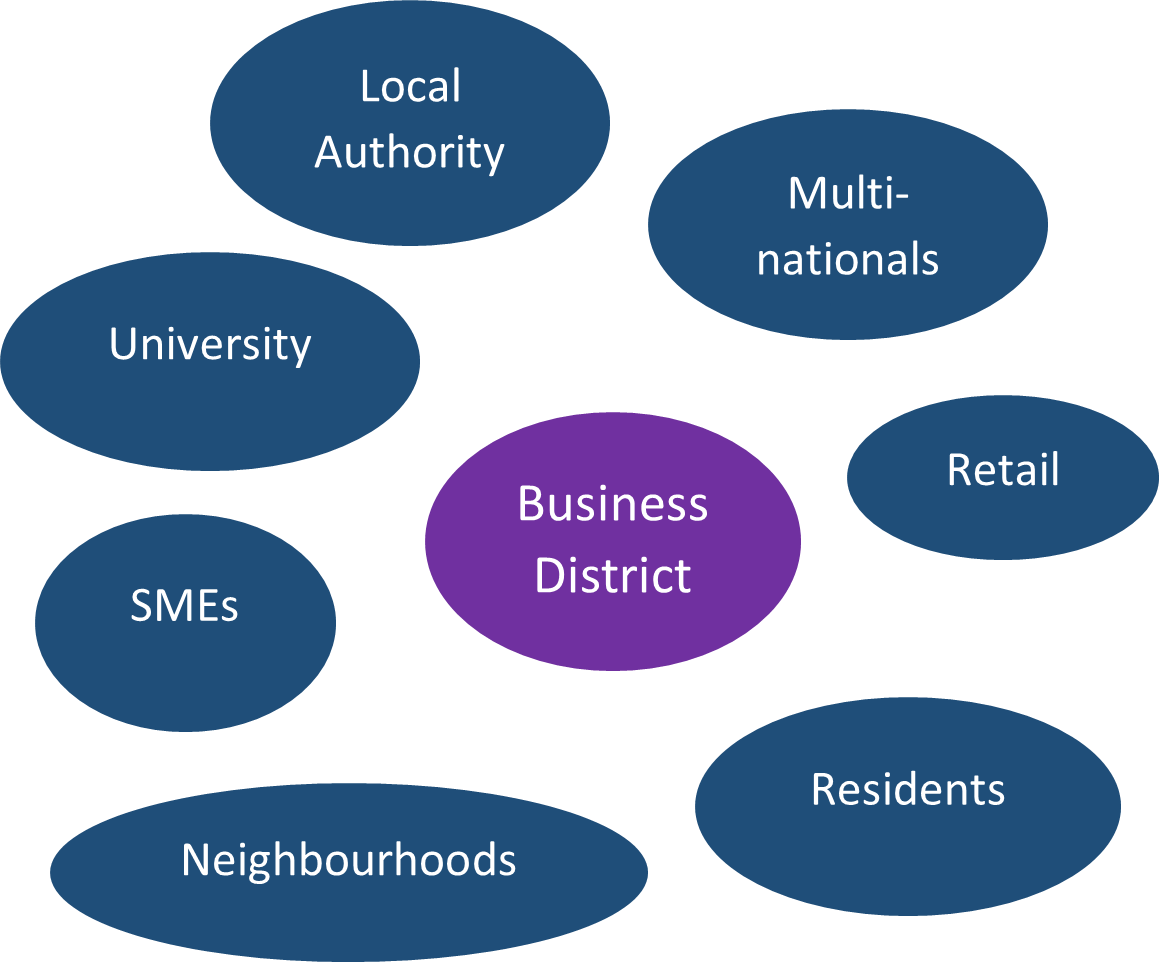

In countries like Ireland and the UK, legislation was introduced in past decades to enable businesses in a defined commercially zoned area to form a company that will take on aspects of governance and carry out certain actions. The legislation allows for a business community to form a Business Improvement Districts (BID) company after holding a plebiscite in the ‘BID Area’ where more than 50% of businesses voted to form the company on the premise of a proposed five-year strategy. If the vote is positive, then a board of directors is constituted with the representation of the local authority ensconced.

Typically, the BID Company will then set up a few working groups that involve local stakeholders focusing on needs identified in the strategy. The BID Company is funded through levies paid by all businesses in the BID area, i.e. the Business District, which are collected by the local authority and then transferred to the BID Company. This amounts to a ‘tax’ paid by businesses in addition to the annual rates owed to the local authority. It also means that businesses have an interest to secure the best return for their contributions. This drives the dynamic of the BID Company as a place-oriented governance structure.

So, how can a BID Company become a vehicle as a post-project structure for governance and implementation of actions in the IAP?

|

| Key stakeholders involved in a Business Improvement District |

The aim of the post-ULG structure can be summarised with the following main features:

- A structure that coordinates the alignment of stakeholder needs in the designated area;

- A structure that provides and supports leadership in the designated area;

- A structure that can facilitate delivery of actions and the measuring of impacts.

In the case of business districts, the stakeholder interests that should drive future development are not only those of landowners or large employers. An interesting case study is the former large industrial estates that have transformed into mixed use business districts, i.e., with new clean manufacturing, office, education, retail and residential uses. One example of how this can work is the Sandyford Business District in Dublin, Ireland.

More than 20 000 people work in Sandyford and 6 000 people live in Sandyford. There are approximately a thousand businesses in the district, ranging from multi-nationals like the Microsoft European HQ to many SMEs. Six years ago, the businesses voted to form a BID Company. Last year, the mandate for the company was renewed with a second plebiscite.

|

| Poster for the Sandyford BID Company |

The Sandyford BID Company developed a comprehensive strategy with actions for the next five years covering not only the marketing of the district, but also greening of the district; significantly increasing active transport infrastructure for walking and cycling; increasing permeability and access to the district; and using new technologies to make the district ‘smarter’.

The BID Company’s approach is to work in collaboration with local stakeholders, including the local authority and residents, with the aim to build a sense of place and community.

The statutory BID structure ensures that the BID Company has a steady funding stream for the next five years to implement its strategy. The BID Company has however learnt from the previous five years that it is even more important to build the trust with key stakeholders to create a culture of collaboration. This in turn will ensure synergies in the use of resources and a collective responsibility for the future development of the business district.

There are significant elements from the structure of BID Companies which cities could transfer to their own governance structures for their commercial areas or business districts. The attraction is the certainty of sufficient resources for action implementation together with an approach to build relationships with key stakeholders, thus creating a vehicle for ‘distributed’ place leadership which also involves the business leaders in the city.

And a bonus, #4: let’s keep the conversation open!

We acknowledge that there are numerous other governance models to be considered. Our purpose was to start this conversation and make use of the incredible knowledge resources that exist in the URBACT programme – URBACT cities pioneering new ways of governance, lead experts with core expertise in innovation and governance, decades of work by URBACT Secretariat members to design capacity-building activities to make collaborative work in ULGs and beyond possible, just to mention few examples. Several workshops within the URBACT City Festival in June 2022 highlighted the continuation of ULGs’ work in many Action Planning Network cities. Whether they live on as legally-binding structures, or informal meet-ups, we look forward to watching these local URBACT-sparked connections keep on thriving!

This article was first co-produced by Anamaria Vrabie, Eileen Crowley and Wessel Badenhorst in April 2022.

Anamaria Vrabie is the Lead expert for the URBACT Tourism-Friendly Cities Action Planning Network. She is a behavioural-informed economist and leader of urban innovation practices with over 15 years of international experience. Since 2017 she has co-designed and managed Cluj-Napoca Urban Innovation Unit. You can reach her at anamaria.vrabie@urbaninc.org.

Eileen Crowley is the Lead expert for the URBACT Resourceful Cities network. She is a project designer and planner. Having worked for almost 20 years in local & regional government, as well as the research sector in Ireland on a broad portfolio of EU funded transnational projects she now works in the private sector as a consultant. You can reach her at eileen@ascentgrants.com.

Wessel Badenhorst is the Lead expert for the URBACT iPlace network. He previously worked as the Economic Development Officer in Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council, one of the Dublin local authorities. He also was the interim CEO of the Sandyford BID Company and helped develop its new BID Strategy. You can reach him at wessel@urbanmode.eu.

Submitted by Anamaria Vrabie on

Submitted by Anamaria Vrabie on