Feed Forward Stories: re-designing public policies & services through co-knowledge production

Edited on

21 June 2019When re-designing public policies for social challenges in cities, do we start with the questions and knowledge of the civil servant, the academic researcher, the youth professional or with the story of a boy in the park? Dutch think- and do tank Kennisland found that when city innovation projects are primarily reasoned from existing (academic, governmental) institutional cultures and interests, they run the risk of becoming mere brave attempts to repair inherently broken systems. To arrive at new, more inclusive relationships between citizens and the state, with new (and hopefully better) practices and outcomes on the ground, Kennisland developed the co-knowledge production methodology ‘Feed Forward Stories’, which actively engages a multidisciplinary team (including policy makers, social workers, researchers, artists and citizens) in the traditional knowledge production chain of policy making and (social sciences) research.

Feed Forward Stories starts by questioning assumptions on change with people and their stories on the streets, in parks, at schools, in neighbourhoods. What do they aspire to in life? What enables and disables them to thrive? From these narratives, we move to the stories of people operating in the system: how do they work, what can be done better? From there we develop innovative new practices to start change together, ranging from crowdsourced social city mapping, flipping the policy-making cycle, swapping old success indicators for new ones, designing infographics instead of publishing thick reports. This article introduces Feed Forward Stories and illustrates its use in two case studies: a ‘social lab’ with discouraged youth in Nijmegen (NL) and a ‘social lab school’ with homeless people in Hong Kong (CN). What kind of challenges do the lab teams encounter in their urban environments?

Good intentions, bad outcomes

The boy who got lost in debt and piles of paper while lacking a postal address to start his debt cancellation procedure, and thus his new life.

The policy maker who has good connections but lacks the numbers and stories to take grounded action.

The politician who tries hard to make the right decisions, while avoiding favouring one group of citizens over the other.

The youth professional who bounces back and forth between providing what the boy needs, and what the bureaucratic rules require.

The (social) entrepreneur who identifies social needs but lacks fair start-up conditions.

The academic who wants to do meaningful work but is stuck with an academic ‘publish or perish’ system that incentivizes them to lock their knowledge behind expensive doors of academic publishing companies.

All of these people live in the cities we’ve worked in: Nijmegen (NL), Dordrecht (NL), Amsterdam (NL) and Hong Kong (CN). They often have the same good intention: to make things better for themselves, for the city, the world. But what we see in practice is that their stories are (often) disconnected. So although the intentions are good, the outcomes are bad: discouraged youth, overworked youth workers, policy makers stuck in bureaucracy, academics with underused capacities. And they also don’t get to know each other: people naturally tend to strengthen their own networks by looking for the known other, while leaving the stranger out of sight. How to connect the stories in our cities and start open, accessible, socially innovative practices? One method which is internationally spreading is a social innovation lab* (*sometimes also called a public sector innovation lab, hereafter referred to as a social lab).

Social lab settings

Social labs are hailed, even hyped worldwide as vehicles for transforming the way our cities, our schools, our energy supply chains and welfare programs run. The concept of the social lab is derived from closed, controlled experimental labs in universities and technology companies. In contrary social lab practices take place in curated but nevertheless inviting spaces at the heart of where social life actually happens: homes, families, neighbourhoods, communities, districts. Social labs are run by local, multidisciplinary teams consisting of both citizens and employees from institutions: professionals, (local) government officials, policy makers, researchers, teachers, artists. In these teams everyone becomes an expert or layman in their own way. Various methods are employed to expose and discuss realities and myths: publishing all the material on an open blog, organising collective knowledge cafes where stories are discussed and new ideas are prototyped. Along this process of reconnecting stories, new insights, behaviours, interactions and perspectives for action emerge. While labs can run from anywhere between a week up to a year, they always have the explicit intention to be temporary. In this way the lab leaves no self-interest behind, just a new reality in which new relationships and initiatives unfold of their own accord.

Three social lab work principles:1. A lab is open and inclusive: walls are porous to allow public negotiation 2. A lab is focussed on research and action: thinking without doing or doing without thinking is not allowed in a lab 3. A lab takes place outside: a lab must do justice to the complexity of the outside world, only variety beats variety |

Feed Forward Stories

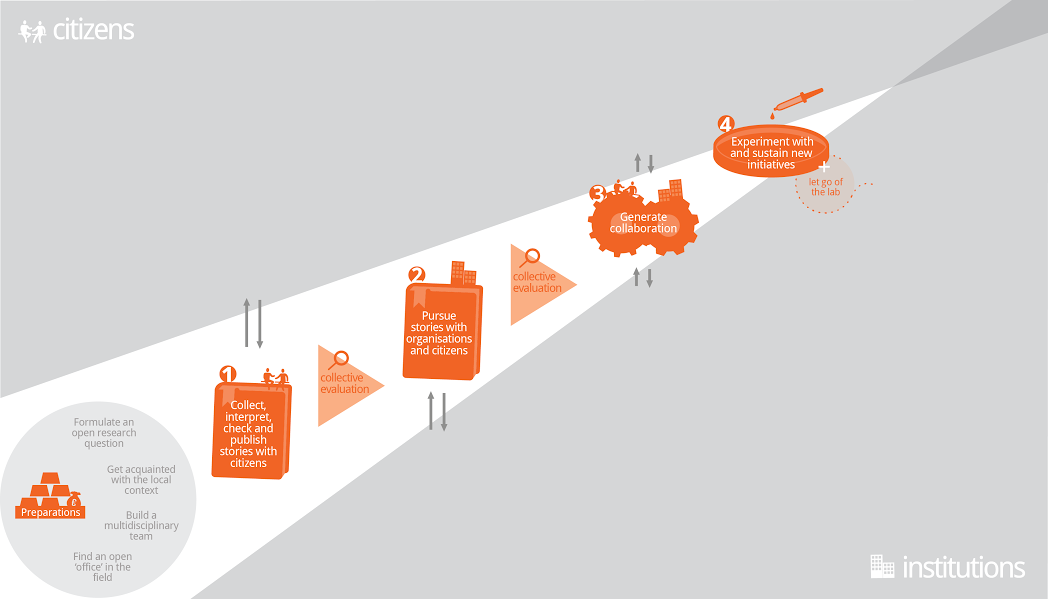

Through social lab projects with youth and elderly people in Amsterdam (duration: two weeks), Dordrecht, Nijmegen (duration: both six months) and lonely/homeless people in Hong Kong (duration: one week, in the form of a ‘school’), Kennisland put in effort to develop, prototype and improve its own social lab approach: Feed Forward Stories. Feed Forward Stories, short for stories that contain feedback to move forward, is a way to open up traditionally expert-driven practices like research, policymaking and innovation methodologies to people. In four simple, guided steps the lab teams collect and interpret the stories of citizens’ lives and their experienced challenges (step1: stories with citizens).

As a follow-up the lab team evaluates collectively with the public and chases emerging thematic threads up to institutional levels (step 2: check stories with people in the system). The unexpected meetups between previously disconnected stories and disconnected people give rise to a new narrative that consciously abandons its old patterns, and creates new ideas, actions and prototypes (step 3: prototype actions). This new narrative ultimately prompts more sustainable behaviours and patterns in making public policy and public services that are better connected to lived, social realities (step 4: sustain actions). As they move forward, the written or filmed accounts of the encounters are all published on a public blog that serves as a constant eye witness; an evidence-based story database.

This is how we can move from stories about poor youth in debt who gain social status through stuff they buy through instalments (step 1), to stories from youth workers who acknowledge that material youth cultures are not yet addressed in their projects while teachers wonder why youth workers are never in schools (step 2) to prototype an art lesson to spur thoughts on how it can be cool to live a minimal, non materialistic lifestyle (step 3) to sustaining this idea in a new youth work and school policy that enables a series of classes taught by youth workers in schools each year (step 4).

As such, Feed Forward goes beyond mere individual researching, recording and understanding of a situation. Instead the team engages in a continuous, collective, open, digital and multi-medial “knowledge negotiation” that actively shifts ownership over innovation and change from the system to the citizens and back.

Good intentions, better outcomes?

One of the results of Feed Forward Stories in the social labs we have conducted in Amsteldorp (on elderly well-being), Hong Kong (on homelessness), Dordrecht and Nijmegen (on youth well-being), is that Feed Forward acts as a catalyst for existing and new initiatives by/for citizens. By bringing strangers together on the basis of different and shared interests, ambitions and relationships, new initiatives arise, ie. a new meal service in the neighbourhood, a new local talent platform for youth that connects them with other talents in the city.

Secondly, results are generated on the level of ‘systems’. As professionals and local government officials enter the field with open questions (ie.“What is it like to grow old in Amsteldorp?” ‘How is it to be young in Nijmegen”?), stories of citizens exposed what the (policy-making) system could do better to support citizens more effectively. Examples are: a positive social network map that lists all the initiatives for both official help and unofficial fun for youth in the city; a learning network between professionals and civic administrators; an infographic as a tool to show how local youth policies are currently made and what could be done better; experimenting with the use of stories besides numbers in the statistics department; taking up prototyping as a new condition to grant the second instalment of subsidies for youth projects.

Thirdly, the social lab generates results on the level of individual and organisational learning and innovation in cities: labs attempts to engage everyone in the lab teams and their immediate surroundings in an act of collaboration and learning over newly generated knowledge on social innovations. People start to question their own practices. “Should we not more often generate stories when we are in need of new policies?”, reflects one policy-maker. Once the learning starts, own actions follow. A teacher at a local college in Nijmegen: “I am now using the infographic we made on policy-making in my class to teach my students how we could re-think the role of the social worker in policy-making”.

Most importantly, we find that a more democratic, inclusive method of producing and analysing knowledge that helps to break through existing (political) power structures to put the interests of citizens first while collaborating over these interests with the systems in place. Especially in Hong Kong, where we introduced our very first ‘lab school’ to teach local students, researchers, professionals and civil servants how to work with Feed Forward in the case of homelessness it became apparent how sturdy and hairy reality is in more closed cultures: no politician or high-end manager turned up at the end presentations of the teams while hardly any NGO opened up their doors. Luckily the labteams themselves reflected on their experiences with statements like ‘this is a real eye opener’ and ‘what a learning experience!’. Especially going out on the streets to collect stories, prototyping ideas and going back to check the results with homeless people were mentioned as new assets they had never done or learned in their schools, municipalities or universities.

Future challenge: co-knowledge production in cities

Feed Forward Stories allows all involved to become researchers and policy makers of their own challenges in their own urban settings. This co-knowledge production methodology implies a change in the way knowledge in policy making and research practices is produced (away from the city hall...away from the university… how about a park?), how its quality is evaluated (away from external evaluation by objective experts ...how about an open blog?) and the way output looks like (away from the PDF or paper report … how about a podcast series, a booksprint, a social map?). This is a daunting challenge, which is confronted by entrenched work cultures.

Lab team members reported defensive questions from their immediate colleagues like: “Why do you want to do it differently? What is your evidence for that? Show me your numbers, what is your immediate impact?”. The same culture favours immediate work over learning about how to improve work: when something ‘more urgent, more important’ turns up, lab team members often have to give up their lab day or they are stared at by colleagues and bosses. Also lab teams are met with heavy local competition from social (well being and care) institutions who compete for the same (diminshing) budgets and therefore actively deny access to ‘their citizens’. And lab teams have seen discouraged citizens, who are cordially invited to “tell their story” and are soon forgotten after six other bullet points on the busy agendas of the local aldermen. If you consider starting an innovation project in your city, then we have four questions to leave you with when you decide to set up your social lab in your city.

Happy labbing!

1. Who are your co-’s? There is much talk about collaboration, but if we keep collaborating in our own networks, then we run the risk of strengthening or even favouring existing power relations without really challenging social issues. Think about who really needs to be invited, and think of the people you hardly see or know yourself. 2. Do your co-’s want to work together? In practice we find there are more people who do not want to work together than people who do. We do encourage to connect exactly those people who seem to not want to work together and facilitate ‘gentle conflicts’ to open up real dialogues in systems that are stuck. 3. What do your co’s usually do? Cultural practices usually stay the same for a long time, making change slow and often too insular. It helps to use different artefacts (stay away from the conference, the beamer, the stage, the keynote, the meeting, the abstract, expert language) and make everything you attempt to do into a co-knowledge production (write a blog together, make a podcast together, meet outside institutions where others can join) 4. How to support the co’s? If one separates the experiment of making new policies and designing new types of research methods from ‘the real policy-making process’ or ‘the real academic process’ one runs the risk of working in the margins. Settle your lab in the middle of the system, seek high-end supporters who protect the efforts of your lab team and involve the ones in power in what it is you’re trying to establish as a team. |

Submitted by Marlieke Kieboom on

Submitted by Marlieke Kieboom on