From non integrated to integrated urban development: an illustrated story

Edited on

31 March 2017

Read time: 15 mins

There are many ways to explain what integrated urban development is, or should be. One of the ways is to show examples on the opposite, i.e. on non-integrated solutions for urban development. Here we bring up three examples in the areas of poverty, ageing and economic development and reflect further on what integrated urban development is and how to put it into practice.

Poverty

In some European countries on can find threatening examples of extreme poverty and area deprivation.

The first picture below shows such a situation at the edge of Sofia.

Many governments and municipalities want to act on such situations, putting the poor people under better conditions. However, very often such efforts are taken in non-integrated way, leading to very limited results.

The picture in the middle above shows a container settlement at the edge of Belgrade, to where Roma families, who were living in shacks under a bridge close to the center, have been moved to. Although their housing situation might have been improved a bit, they were in practice expelled from the inner city (which gave them some possibilities to earn their living) to the remote periphery.

There are much better, more integrated solutions possible to handle extreme poverty.

The picture on the right above shows the case of a Hungarian village, Sirok, where Roma families were living in caves at the edge of the village. In the framework of a national programme on the elimination of ghetto colonies a foundation has set up an integration strategy, bought some houses within the village and the families could move from the caves into normal housing in integrated environment (one of the houses was just opposite to the house of the mayor of the village).

Besides radically changing the housing conditions the programme also included ’soft elements’, such as training for the adults and help to get in employment, orienting the children into non-segregated school classes, setting up Roma associations to continue the integration beyond the programme.

Key elements of the success were the national framework programme ensuring the integration of hard and soft aspects and also delivering financing; and enthusiastic NGO-s on the local level, implementing the programme.

Ageing

European cities are ageing. In some cities it becomes quite visible, as for instance on the picture on the left below, showing a square in Barcelona.

The challenge of ageing can be handled by direct, one-dimensional interventions, such as building moving escalators (picture of the middle above, Barcelona).

Besides such non-integrated (though quite useful) interventions also other, more integrated solutions can be suggested, such as the idea of intergenerational housing cooperatives where elderly people live together with young adults in order to help each other (Picture on the right above).

The management of ageing-related risks through intergenerational housing schemes can promote longer, healthier and more independent ageing, while having also a positive impact on the cost of healthcare policies for both the families and the public authorities.

Economic development

As a consequence of globalization, the sharpening economic competitiveness requires cities to attract the most modern technologies and talents. The first picture below shows a workplace in a modern factory in Hungary.

In the last decades the answer of cities on the economic-scientific challenge was the erection of science parks, usually as own urban entities, situated out of town with poor public transport links and extensive car parking. The picture in the middle above shows the science park of Oeiras in the periphery of Lisbon.

There are many externalities to one-sided solutions such as science parks. Segregated science parks are ’soaking out’ highly qualified people and students from the inner parts and normal life of the city, reducing social mix, creating huge car traffic, etc.

A more integrated answer on such economic challenge is for instance the development of knowledge districts within - or linked to - the already built-up parts of the cities, aiming for mixed-use.

The picture on the right above shows the Arabianranta mixed-use area of Helsinki. There many different functions can be found: coworking spaces, incubation, finance, SME support clubs, cafes, bars, restaurants, 24 hour life, walking, cycling, tram (but less parking), creches and local services. The area is home for 10,000 people, a workplace for 5,000 and a campus for 6,000 students and know-how professionals. As a residential district, Arabianranta is heterogeneous, with different types of housing: modern loft buildings, city villas, homes for groups with special needs such as community housing for active elderly people and residence for mentally disabled juvenile.

From these examples it can be seen that the main problem with the non-integrated, one dimensional, sectoral solutions lies in the externalities, the sometimes very serious negative consequences along other dimensions. In the poverty example the container camp improves somewhat the housing conditions of the Roma but their (formal or informal) job/survival opportunities decreased radically with the peripheral location, from where the inner city became unaccessible. The science parks separate the higher qualified people from the city and it is not even sure that they feel/work better in such sterile environment than in ’normal’ mix used urban areas.

The development of integrated urban development and types of integrated approaches

No wonder that the issue of integrated development came to the forefront in the last decade or so, not only in local matters but also regarding the key questions of urban development at large. This was the starting assumption of the European Commission Cities of Tomorrow report (2011): the very diverse challenges ahead the European cities, ranging from ageing, climate change, through globalisation till the rising inequalities and socio spatial polarisation, can only be tackled with integrated interventions. This means that each of these challenges can only be handled in ways which do not increase the problems in regard of other challenges.

One of the first mention of the idea (with other words) was the issue of sustainable development in 1987, when the Brundtland report called for the integration of economic, environmental and social aspects. In the following decade integrated development gained ground in the EU and step-by-step the URBAN programme has been developed with the aim to integrate hard (physical) investments with soft (social) measures in urban regeneration.

Despite the fact that URBAN was only an optional Community Initiative with low level of financing (compared to the mainstream Structural Funds programmes), it became one of the most successful EU programmes. The integration of the two main aspects was required on the case of deprived neighbourhoods in the cities, via the compulsory cooperation between the different sectoral departments of the city hall.

In the course of the URBACT programme a more precise understanding of integrated urban development has been developed, distinguishing three different aspects of integration:

- horizontal integration: cooperation across the different sectoral policies and departments (e.g. infrastructure, housing, education, social matters, culture, environment …) to address jointly a specific challenge; all sectoral decisions should be controlled regarding their effects on other sectors, recognizing that integrated development might require sub-optimal solutions along each dimension in order to reach good balance between all dimensions

- vertical integration: cooperation between the different levels of administration, i.e. between the vertical chain-links of government to ensure coherence; higher levels of government can influence the outcomes at the lower level, while cities can achieve more with the support of regional and national frameworks.

- territorial integration: cooperation between the adjacent municipalities in functional urban areas/metropolitan areas to ensure that negative externalities are not passed on across the administrative border of the city and to avoid displacement whereby problems are solved in one area but pop up elsewhere.

The chapter written by Peter Ramsden on Disadvantaged Neighbourhoods in the first edition of the URBACT Project Results discusses many URBACT projects as good examples on horizontal and vertical integration: Co-Net, LC-Facil, NODUS, Reg-Gov.

Theoretically all aspects of integration should be applied at the same time in harmony with each other. This is, of course, impossible – cities and mayors even with the best ideas have to face political realities and can only achieve their ideas with unavoidable compromises.

The above discussion of integration refers to the level of the municipality (urban area). It is also possible to raise the issue of integrated approach in regard of a programme or a project: whether the applied solution considers all of the economic, environmental and social aspects, not favouring too much any of these at the expense of the others.

Now let us see some examples on the different approaches to integrated development.

Integrated urban development at the level of the city or of the urban area

Most cities have long-term strategic development plans. There are huge differences, though, on how integrated these plans are and to what extent they steer urban development in reality.

The STEP 2025 Urban Development Plan adopted in 2014 by the city of Vienna can be taken as an example of a well developed integrated vision.

In the Plan, as a starting point, the scenarios for population development until 2025 are analysed. The most probable version forecasts 170.000 population increase by 2025. It envisaged that, taken into account demolition, 120.000 new housing units should be built.

Vienna is a good case for integrated urban development within the city but less so regarding territorial cooperation with settlements outside the administrative border.

This can be seen in STEP 2025, which deals with the urban development and housing aspects of cooperation with the surrounding area only quite briefly and only lists the tasks to solve, without concrete plans. Territorial integration seems to be weak – at least regarding the narrow vicinity of Vienna (the plans for the broader Centrope metropolitan area are more developed). Thus the city has to solve the urban and housing aspects of the urban growth challenge more or less within its administrative borders.

Regarding the city territory, development targets have been calculated for different parts of the city (historical inner city, brownfield areas, peripheral built up areas, new areas to be built in), applying the criteria of growth management and compact urban development. Due to the substantial growth challenge, it is unavoidable to use areas outside the already built up structure of the city. For the new urban quarters STEP 2025 raises a series of conditions: to offer urban quality and diversity, be affordable and comply with all sustainability aspects, e.g. with regard to energy efficiency and mobility.

Another important requirement towards the new areas is relatively high density (as the city can not influence growth outside the city borders). Urban density is calculated in relation to the level of public transport service. The plan mentions that „Future urban expansion projects for development axes along high-level public transport corridors should therefore predominantly reflect densities of a minimum net floorspace ratio (NFSR) of 1.5; in the vicinity of high-level public transport, the minimum NFSR should be 2.5. With especially positive location factors, higher densities are possible on a case-by-case basis in some areas in the context of high-rise developments”. This is a special application of the transit-oriented development (TOD) principle, initiating higher densities in areas better served by public transport.

The biggest new development outside the already built up structure of Vienna (but within the administrative border, see on the map on the left below) is Aspern Seestadt, a new residential quarter on a former airfield. The details of this development have already been discussed in an earlier article.

The recent picture about the already built up part of Seestadt (Picture on the right above, taken from a drone) illustrates that the TOD principle has been taken seriously – high density has been created as the quick and convenient metro connection to the city centre is already in place. Besides the high urban quality and energy efficiency also diversity is aimed at. The size of the new flats ranges between 45 and 160 square meters, and half of the units are subsidized public rental flats. This is to ensure a good social mix as the larger and owner occupied flats will obviously attract middle class families.

As mentioned, the limit to consider Vienna as a good practice in integrated urban development is the low level of territorial integration.

Working together across the administrative border is a difficult issue, not easy to handle if municipalities have high degree of freedom in regulatory and financial matters and there is a lack of higher level (regional or national) policy to initiate metropolitan cooperation.

In this regard France is a much better example than Austria, as in France several national laws (e.g. the Chevènement Law of 1999) have been passed to foster the cooperation between municipalities of the same functional urban area. As a result, all urban areas in France with more than half a million inhabitants (except for Paris) are urban communities, having according to the law joint administration for the core city and surrounding smaller settlements. This 'conseil communautaire' (community council), composed of a proportional representation of members of municipal councils of member towns, has the responsibility to decide in the most important policy fields of the larger urban area: strategic planning, transport, housing, etc.

Integration on programme and on project level

The easiest understanding of the integrated approach is that economic, environmental and social aspects are all considered when looking for a solution and neither of these becomes dominant over the others. However, it is not simple to determine what are the criteria for a project to be integrated. In a normal case the inherent project logic usually goes for sectoral, non-integrated solutions, thus some special aspects are needed to push the process towards considering integration.

Below, I try to summarize some aspects which might help those who want to alter the usual project development processes towards more integration.

Projects which are part of an integrated planning framework get good chances to become integrated themselves.

Higher level integrated redevelopment frameworks for urban areas, such as the EU URBAN Community Initiative (1993-2006), the German Soziale Stadt programme, the UK New Deal for Communities (1997-2007) paid high attention to define their approach towards integration, on the basis of which projects were selected.

The New Deal for Communities programme was launched in the UK 1998 with the aim to reduce gaps between deprived urban neighbourhoods, in which decades of classic regeneration policy had not showed many effects, and the rest of the country. The core budget for the ten year period was 2 bn GBP for 39 programme areas. Key fields of intervention were work, security, education and training, housing and the physical environment – with a compulsory but locally determined mix between these social and physical measures. There were also Local Strategic Partnerships to be formed to promote cooperation across relevant public, non-governmental and private actors. (Tosics, 2015)

Individual projects, not being part of any vertical integration scheme, have to aim for horizontal integration. To achieve a balance between economic, environmental and social aspects needs special efforts. Probably the best is to raise an extra impetus for the integration of sectoral aspects: either concentrating on deprived areas (as URBAN), or aiming for sustainable development or requiring innovation, e.g. more efficient (less costly) public services as a reaction on the financial crisis.

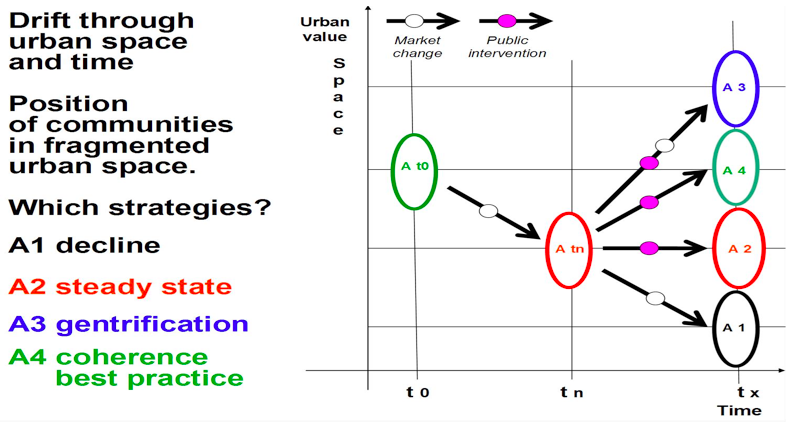

Regarding urban regeneration, a potential measure of integration has been developed by Claude Jacquier.

The picture on the left shows how he analysed the options for public intervention in a deteriorating building (or area) from non-intervention, leading to further deterioration (A1) to the most costly intervention (A3), leading to gentrification. The difficult task is to find and apply the A2 or, even better, the A4 options, i.e. those levels of public interventions into regeneration which stop physical deterioration or even bring some improvement, without significant gentrification. These are the solutions integrating the economic/physical and the social aspects.

The picture on the left shows how he analysed the options for public intervention in a deteriorating building (or area) from non-intervention, leading to further deterioration (A1) to the most costly intervention (A3), leading to gentrification. The difficult task is to find and apply the A2 or, even better, the A4 options, i.e. those levels of public interventions into regeneration which stop physical deterioration or even bring some improvement, without significant gentrification. These are the solutions integrating the economic/physical and the social aspects. Sometimes even the best ideas for integration face difficulties to reach the final aim. An interesting example for that could be found in the Magdolna Quarter social regeneration programme in Budapest.

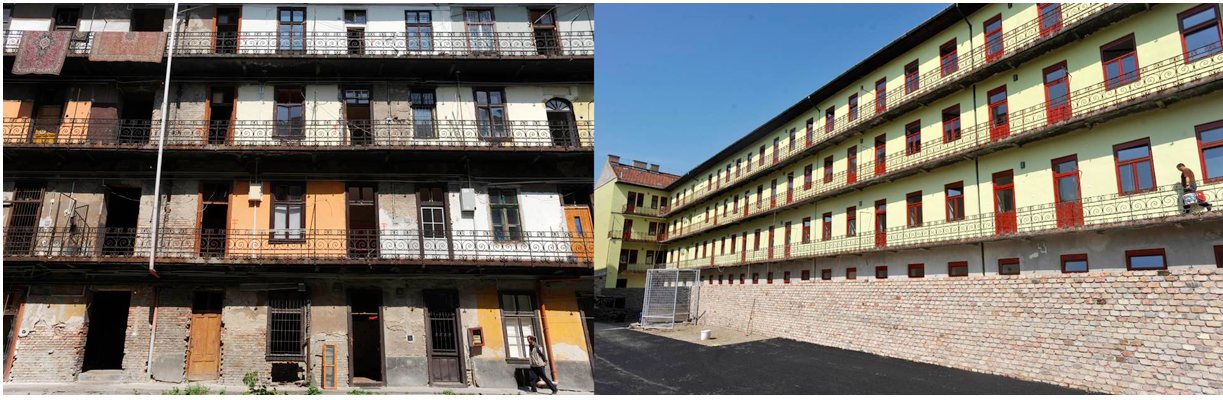

As part of the area-based programme planners faced the dilemma of what to do with a derelict building, consisting of 40 small one-room flats with no conveniences at all. Finally they opted for an integrated solution: to upgrade the building for the same, very poor tenants. Thus the tenants have been moved to temporary accomodation and the building was renovated and modernized: all flats got a toilet and a small shower.

The picture below of Magdolna Quarter in Budapest shows a building before and after the modernization.

Source: RÉV8, György Alföldi.

After the completion of the renovation the original tenants were offered to move back but to the greatest surprise of the planners, most of them rejected this. The reason was the missing link between physical modernization and social affordability: for the poor tenants the introduction of flushing water into their homes created a new cost item (the expensive water charge) to pay for which they did not get any income-related compensation from the social security system. In this case the bottleneck for reaching an integrated outcome was outside the remit of the local planners: the lack of a comprehensive social protection system.

Integrated urban development is not an easy business – but is the only way to go to deal with the complex and interwoven challenges our cities face nowadays.

Some ideas and illustrations come from joint work with Peter Ramsden.

Themes homepage sticky:

Submitted by ivan.tosics on

Submitted by ivan.tosics on