How do we move? Towards a new mobility behaviour in metropolitan areas

Edited on

29 March 2022Mobility planning has a great influence in the physical and social structure of urban areas. In this article, RiConnect Lead Expert Roland Krebs advocates for mobility planning as a trigger for metropolitan development, where favouring public transport and sustainable mobility can foster new activities.

For many decades since the beginning of modernism in the 1930s, the urban development of cities was based on making the territory accessible for cars. The concept of the separation of functions through zoning (see: “The Athens Charter”, 1933) and the increased speed of how we move around the territory led to a spatial dispersion of uses and subsequently, urban sprawl. This resulted in territorial fragmentation, increased usage of natural resources, pollution, accidents and so forth. The infrastructure that was created after the post-war economic boom led to barriers in our cities, not only in the historic city but also in the metropolitan area. These mono-sectorial planning decisions of road infrastructure projects - mostly national public investments – left scars in our metropolitan areas that resulted in a separation of inhabitants by their social or migrant status, gender, religion, and other factors.

RiConnect contributes to the discussion of these topics; mobility planning will be a facilitator for metropolitan development, a true enabler of other interventions in urban regeneration that will be triggered locally. During our first Thematic Meeting of RiConnect’s second project phase in October 2020, we discussed about mobility in metropolitan areas. The goal for RiConnect in the mobility realm is to:

- Support different mobility types to ensure adequate accessibility

- Optimise the use of combined means of transport in favour of more efficient mobility

- Promote mobility systems based on using means of transport that will assure accessibility for everyone

- Create integral and multi-sectorial urban solutions and combine mobility and transportation planning with sustainable urban regeneration of public spaces, local economic development among other disciplines.

Today, the pandemic is heavily affecting the debate, because when public transport is not available or is deemed insecure due to risk of infection, workers and care-workers among other commuters from systemically relevant jobs were cut off from the supply of public transport and they were forced to use the car. On the other hand, the pandemic showed that the public realm locally became more important when people stayed at home during the multiple lockdowns; and active mobility patterns like taking the bike are also becoming to be a true option for mobility – even for long distance commuting in metropolitan areas – however, the infrastructure shall be available and reliable for active mobility. The local municipalities reacted quickly with this kind of temporary cycling infrastructure that was created from one day to the other. Cities like Brussels and Vienna observed over 40 % of increase of cycling in the month of May 2020 compared to 2019.

Figure 1: Temporarily Improved Bike Infrastructure in Vienna due to increase of bike use. Source: Roland Krebs.

So, how can we maintain ‘good’ mobility habits caused by the pandemic in the post-COVID-19 reality? When providing the right bike infrastructure which provides safe rides, people will start using it. However, it is important to allow a transitional period from cars to other types of mobility and to strike the right balance between all different types of mobility. Nowadays, it is also important to explain that public transport is safe to re-balance the mobility share. This will be a challenge for all service providers in metro-areas, however there must be a proper offer of public transport. But providing service is one side of the story, the other is that whenever a new hub is created or upgraded, the (wasteland-)area around it could potentially be integrated in an ecosystem of metropolitan hubs.

Figure 2: Infrastructure as a barrier in the Porto Metropolitan Area. Source: AMP

In the sense of above-mentioned challenges and problems, our RiConnect partner Krakow Metropolis Association (KMA) is working on a metropolitan strategy of de-centralized hubs to create accessibility of the main centre of Krakow and decrease car use in the metropolitan area. Krakow metropolitan area has a wide array of challenges: overcrowded roads, lack of mobility infrastructures and public spaces throughout the metropolitan area, and a lack of good infrastructures and services connecting the suburbs and city core with public infrastructures. To deal with these issues, the metropolis is promoting Integrated Territorial Investments, which act on several aspects in locations all around the metropolis. On the one hand, there is an effort to create a system of Park and Ride areas throughout the metropolitan area associated with train-tram stations or bus loops. In the long term, though, the city is creating a new Fast Agglomeration Railway system to connect city and suburbs and cut travel times in half. And finally, core action is being taken in the city to better integrate existing infrastructures and offer more room for soft mobility. The RiConnect Pilot case of Skawina will develop ideas on how to improve the mobility share to trains and at the same time, regenerate the town centre of Skawina as a hub in the metropolitan area.

Another case study from our partner Amsterdam Transport Authority (VA) showed the success of developing a central mobility hub in the heart of the City of Amsterdam, the Amsterdam Central Station. Located on an artificially created island, the station has kept improving its connections with its surroundings by building new roads over the years. However, the growth of its intermodal status with buses and ferries, the greater need to reach the station by foot or on bike and a growing interest in using the riverside have pushed towards a complete redevelopment of the northern side of the station, formerly occupied by a busy road. To do so, the road has been buried underground, enabling a continuous network of public spaces, and adding commercial areas on the ground floor. A bus station has been located on the first floor instead, and the riverfront has been converted into a promenade shared by cyclists and pedestrians.

Figure 3: 5 and 15 min walking and cycling distance from Lelylaan Station in Amsterdam. Source: VA

In a smaller scale, the RiConnect Pilot case in Amsterdam, Lelylaan Station, wants to replicate the success of Amsterdam Centraal. This station is rated as one of the worst in the country considering its design and feelings of safety. This project will be about an integrated urban strategy to connect the neighbourhood with the station better and create a functional and people-oriented hub in the metropolitan area of Amsterdam.

However, the existing project for Lelylaan, ‘Poort van West’, does not tackle the surrounding areas of the station. With our RiConnect project, we aim to enhance this neighbourhood in cooperation with local stakeholders. We can expect that as the use of the station will increase enormously the coming years, the use of its surroundings will also increase. Yet, this area is not yet designed as (socially) safe, comfortable, and enjoyable. With the input of stakeholders from within the area, we aim to enhance the area and come to solutions that are experienced by the area’s everyday users.

Figure 4: The heavily fragemented Barcelona Metropolitan Area. Source: AMB

Mobility planning is the most powerful discipline for the development of metropolitan areas; it was before, but it is even more post-pandemic; however integrated solutions are required to trigger sustainable, green, just urban development (see: “The New Leipzig Charter”, 2020). For RiConnect partners the potential development vision would be mobility-hubs in the metropolitan area as sub-centres in a system of centralities, well connected with massive public transportation infrastructure. Those areas could add value through mixed-use patterns including density-housing, services provision and decentralisation of metropolitan functions, local job creation and provision of public space locally but in metropolitan networks of green spaces, in short-distances to reachable with active-mobility patterns. Key to success is communication: active mobility modes are usually safer, cheaper, and faster than cars, yet this message must be delivered successfully. Also, the pandemic has offered a priceless opportunity to encourage cycling and to create friendlier public spaces. Another aspect is the gender sensitive mobility-planning. If everything we do in our cities is great for an 8-year-old and an 80-year-old, and consider the female view of the city, it will be great for everyone. Finally, public transport must be made accessible and affordable, with discounts for children and the elderly, and the payment methods must be kept simple. The public must be made aware of the effectiveness of public transport. In this sense, the RiConnect Network is working on integrated solutions for metropolitan areas with visions that support the metropolis with local action that will improve people’s life significantly.

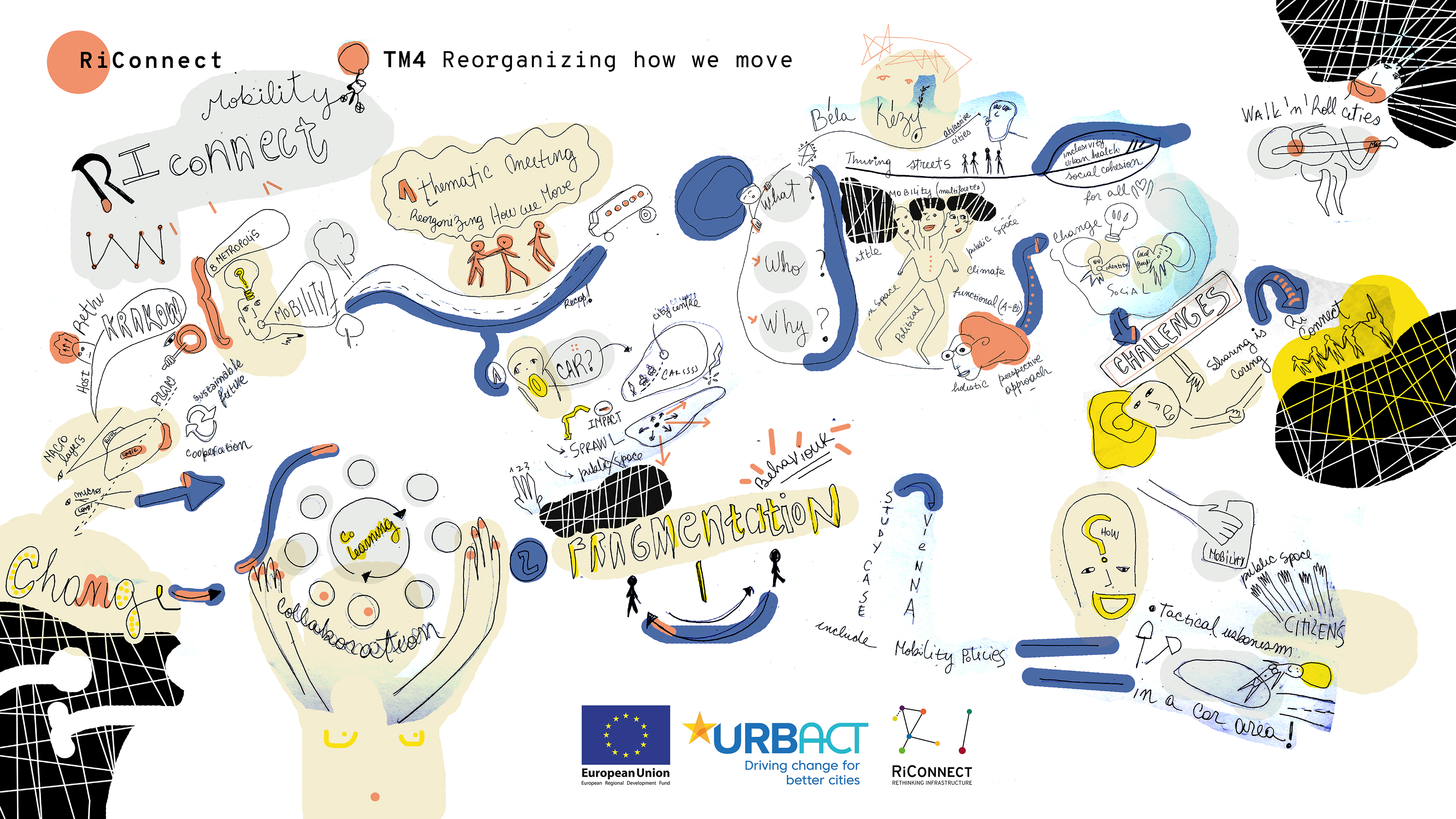

The RiConnect Chronicles 04: Thematic Meeting 1 The network focuses on four themes, which have been discussed in several thematic meetings. Thereore, the RiConnect Transnational Meeting 4, celebrated online in October 2020, dealt with the topic of 'Rethinking how we move', leading to an enriching exchange of knowledge as shown in this article. A summary of the discussion is available at The RiConnect Chronicles 04, a record of events in the order in which they occurred, to highlight the most relevant ideas to the topic dealt with during this meeting. |

Roland Krebs is the Lead Expert of the RiConnect network. He is an Urban planner and urbanist, and director of Superwien urbanism, where he develops strategic action plans for cities to tackle urban growth. He has a vast, international experience in urban planning, design and development, real estate development, land use planning and regional planning.

Cover image: The N3 in the Grand Paris Metropolis - a scare in the city of Livry-Gargan. Source: Google Maps

Submitted by Roland Krebs on

Submitted by Roland Krebs on