Growing cities: How to Expand in a Sustainable and Integrated way?

Edited on

09 October 2017Population growth contributes in many cases also to increase in financial resources. Cities where population and economic growth go hand in hand can be consideredto be in a fortunate position. But how can growing and rich cities be expanded in sustainable way?

Urban development challenges in growing cities

European cities face serious challenges in the upcoming decades. These challenges are well summarized in the Cities of Tomorrow booklet (2011). On the basis of their population dynamism, however, European cities are in very different positions regarding the ways how they can tackle the challenges. Just to mention the two most extreme categories: some 165 million EU citizens live in cities which grow dynamically (mostly due to migration). On the other hand, some 25 million Europeans live in „dynamically shrinking” cities (Gerőházi et al, 2011).

This article deals with the first category, i.e. with growing cities. Population growth contributes in many cases also to increase in financial resources. Let us concentrate now on this, fortunate category of cities where population and economic growth go hand in hand. How can growing cities be expanded in sustainable way?

In this article the main example will be the city of Vienna, while also the case of Stockholm and Munich will be mentioned. All the three cities belong to the happy category of cities which grow both in terms of the population and economy. Under these circumstances all three of the cities decided to create a large new residential area within their city borders: Aspern Seestadt in Vienna, Hammarby Sjöstad in Stockholm, and Freiham in Munich (the first is under construction, the second close to be finished while the third just about to start). The figures are similar and very impressive: in Aspern over 20 thousand persons will live in 10,5 thousand housing units within 20 years from now; Hammarby Sjöstad will soon reach 25 thousand residents in 11 thousand flats, while Freiham is planned to be home for 20 thousand persons.

It is clear that to build large new residential areas is not the only solution in growing cities, there are also other options to accomodate the tens of thousands of newcomers to the city. To create new, compact residential neighbourhoods within the city is obviously better than to allow (or force, if no other options exist) the newly arriving people to spread out to the suburbs. There are cities, however, who aim to avoid the expansion of residential areas even within the city and opt for the (re-)densification of existing urbanized areas. Such integrated „re-use” interventions are discussed in the URBACT Use Act First Thematic Paper (Torbianelli, 2014) on the case of Rome, Dublin and Trieste.

If a decision is taken to build a completely new residential district, this seems not to be a very difficult task – what could limit the phantasy of the planners…? However, the large number of mistakes committed in the past should make the city officials and planners cautious. There are many dangers to avoid when building completely new residential areas in cities. Some of these dangers are quite obvious on the examples of large new areas developed exclusively by the public sector or solely by the private sector.

These dead-end pathways of urbanism, the large prefabricated housing estates and the endless monotonous suburbs, are well known and there are no cities (at least in Europe) which would like to commit now the same mistakes again.

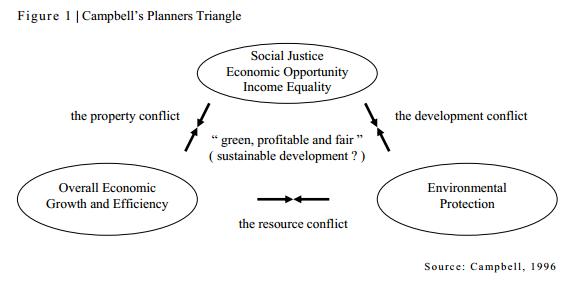

So it is clear what not to do and how not to do it. The main question, however, still has to be answered: how to achieve an integrated new development with a healthy combination of economic, environmental and social aspects? The difficulties are well illustrated in the following figure (taken over from Poldermans, 2005).

City planners and politicians in the three case study cities are all aware about these conflicts and try to handle them carefully in lengthy planning processes, including all types of present and future stakeholders.

The example of Vienna Aspern Seestadt

As an example to illustrate the planning process below some milestones are listed from the long history of planning of the Aspern area:

- Aspern airport was opened in 1912 and it served until 1977 when it was closed down.

- 2003: the start of the planning process for a new residential area.

- 2005: start of masterplanning, announcing in the winner – the Swedish architect Johannes Tovatt brought the idea to create a lake in the middle of the future residential area.

- 2008-2009: first detailed competition about public space.

- 2009: start of the construction of underground line access (as extension of the U2 line).

- 2011: planning competitions for residential buildings, allowing also for co-housing projects.

- 2012: the infopoint, Flederhaus has been opened and the first paths were built at the airfield (which was not accessible for 100 years).

- 2012: IQ is the first completed (office) building, as a plus energy building.

- 2013 October: public transport links opened (underground to city centre and several bus lines) before the first residents arrived.

- 2014: at the beginning of the year the neighbourhood management office has been opened, growing to an office with 15 staff members.

- 2009-2016: the first phase of development has an area of 415000 sq m, for 6500 people.

- The pace of further development: 2017-2023: net development area 470000 sq m; 2024-2029: net development area 197000 sq m.

For the Aspern Seestadt project a specific development agency has been established to develop the technical infrastructure (roads, sewer network, etc.), construct the central lake, lay out the green spaces and deal with the developers of the residential and other functions in the area.

With the commissioning of the Aspern/Essling geothermal plant and the connection of Aspern Seestadt to the district heating grid of Vienna there is a far-reachig self-supply with renewable energy achieved. The link to the district heating grid also allows to fed in heat that would otherwise get lost.

Currently 14 developers (and one co-housing organization) are active in residential development in Aspern. From the 2500 flats in the first phase 1/3 are subsidised while 2/3 follow the rules of subsidized housing with no subsidy (allowing for some public control). The size of the new flats ranges between 35 and 110 square meters.

The ground floor level of the new buildings is built with higher ceiling to allow for office, shop, art-workshop functions and the renting out of these places follows a specific process, through a dedicated company. Instead of building a shopping centre local supply will be assured in walking distance with appropriate shopping mix.

In connection with the high level of public transport, car parking supply is seriously limited to 0,7 car/flat norm (much lower than the 1-3 car/flat ratio in the surrounding areas…) Developers do not have to build many parking spaces but have to contribute with 1000 eur/flat to a Mobility Fund from which biking (rental bike system, e-bikes and cargo bikes) and car-sharing systems are supported.

This short summary shows a series of new, innovative methods in Vienna urban planning: dedicated development company, high importance devoted to public space and mobility, ground-floor planning, co-housing, strong emphasis on neighbourhood management… In fact in Vienna the Aspern area is considered as a Living Lab in the Smart City agenda.

Dilemmas and trade-offs to achieve balance between environmental, economic and social goals of development

The short summary above shows that in the planning process of Aspern Seestadt all principles of sustainable urban development have been applied. More or less similar is the case with Hammarby Sjöstad in Stockholm and the same is foreseen for Freiham in Munich.

Thus the three rich and environmentally conscious cities build their new housing areas along the best known principles of sustainable and integrated development. But is this enough to avoid future problems? Is it totally sure that neither of these brave large new urban developments will prove to be in a few decades dead-end pathways of urbanism?

Integrated urban development is a complex process with many dilemmas and trade-offs. Despite the best will of the planners and local politicians we can not be sure about the long-term outcomes of these large-scale projects. Although it is not easy to make neutral judgements and evaluations, the first signs of worry can already be seen in the Vienna and Stockholm cases.

The non-(or only part-) fulfilment of the original ecological aims

According to Poldermans (2005) in Hammarby Sjöstad the original parking norm was between 0,4 and 0,55 car/apartment, which has been increased to 0,7 when the political leadership of the city has changed. This might have been contributing to the fact that the aimed very high value of 80-90% share of public transport in work-related travel has never been reached – the maximum was 70% (which is also relatively high).

Similar problems might arise in Aspern where already now large debates are going on about the lack of parking places and there are also arguments to speed up the development of access roads – despite the excellent public transport connection to the city centre.

The originally planned goal of carbon-neutrality has been given up in Aspern (some of the planned power plants was not built). Thus instead of carbon-neutral it will only be low-energy area, well behind the best examples in this field.

The ambitious plans in Aspern for mixed shops and also culture-oriented use of the groundfloor structures seem only partly realizing: the groundfloor zone is unaffordable on market prices for artists and there is also a discussion going on to turn some of the groundfloor areas into flats.

The trade-off between environmental and social goals

As Rutherford (2013) points out in his critical evaluation, in Hammarby Sjöstad originally 50% share was aimed for social rental flats but this was not achieved as building costs increased and social subsidies were gradually removed since the 1980s, resulting in a push towards privately owned properties. In that way the new housing area could not fight – as originally expected – the existing socio-spatial segregation of Stockholm city, rather adopted to it (Gaffney, 2007).

The sharpest critics has been formulated by Rutherford (2013) in the following way „… the Hammarby project constitutes a clear case of (at least partial) gentrification with the selling off of public land to developers and then to relatively wealthy households. The City imposed environmental measures on developers who pushed their prices up so that only wealthier households can now afford to buy an apartment in the district, resembling a form of ‘bourgeois environmentalism’.”

Regarding Aspern it is too early to talk about the social outcomes. First signs are quite different from the case of gentrifying Hammarby: the real estate value in Aspern is relatively low, even compared to some working class inner city areas of Vienna, as Aspern is considered to be too far out from the city. Thus there is a danger that instead of the aimed social mix an unbalanced social structure might develop with the dominance of lower income families. This would not be an unique case: in the Munich Riem area (similar new residential development) there were many planning efforts to create a mixed area both regarding offices and residential and regarding different income groups. Recent analysis, however, shows the dominance of low income people.

Trade-off between building extraordinary new areas and regenerating the existing deteriorating housing stock of the city

It is always a big question, where to concentrate public efforts to improve the sustainability of the city in an integrated way. Not even the richest cities can afford to create new eco-friendly areas and regenerate their existing outdated and/or deprived neighbourhoods at once.

There are a number of interesting examples in Europe with sustainable regeneration efforts concentrating on existing urban areas. The case of Wilhelmsburg in Hamburg is one of such examples, where a 7 year long IBA process has been established with the explicit aim of energy-led improvement of the existing low prestige neighbourhood (see Czischke et al, 2015). Also the earlier URBACT publication on building energy efficiency (Borghi et al, 2013) includes interesting information about interventions into old neighbourhoods of cities.

The importance of the sustainable regeneration of existing urban areas has also been shown by the 2014 Bloomberg Mayors Challenge. In the competition of European cities one of the leading topics was to find innovative approaches to tackle the growing problems of outdated multi-family building areas. Very different technological innovations were suggested (e.g. to use drones to discover heat losses of buildings, or to introduce user-friendly IT systems with detailed data) to boost the interest of the population towards energy efficient renovation.

Conclusion

Vienna is one of the most liveable and sustainable cities of the world, with strong traditions also for social equality. The case of Aspern Seestadt illustrates well, how much efforts the city takes to develop the new residential area for the expanding population in sustainable and integrated way.

Yet there are serious dangers in such projects – it is not at all easy to plan future housing areas of such a big size, achieving environmental, economic and social goals at once. There are already now examples on modifications of the originally aimed targets. The financial crisis has reached also the richest cities which also have to decrease subsidies and give up some of their most ambitious plans.

When the economic and financial circumstances deteriorate, changes, adaptations to the new circumstances are unavoidable. Such changes do not create huge problems if they only mean modifications of priorities within the same principle – e.g. the less ambitious carbon standards are partly compensated by the still high priority for public transport. Larger problems emerge, however, if the changes lead to the rearrangement of priorities between the basic principles. This is the lesson which can be learnt from Hammarby Sjöstad: insisting to the highest environmental qualities leads to irreversible losses in the social targets as with the decrease of public subsidies only the richer families are able to pay for the increasingly expensive (because environmentally high quality) apartments.

Vienna (and also Munich with the Freiham area) can learn from this lesson. The balance between the economic-environmental-inclusive principles has to be checked time to time during the whole period of the development of the new neighbourhood. It is not enough to determine the balance at the beginning – this balance has to be kept also when unavoidable financial restrictions have to be applied, public contributions have to be decreased. The well established neighbourhood management team might be a good basis to discover early signs of emerging unbalances and call the attention of politicians and planners to intervene.

Large-scale new residential areas may contribute to achieve better balance between the different aspects of sustainable and integrated urban development. But this is not easy at all, it needs continuous monitoring of development and flexibility in setting the targets – to avoid the disruption of the balance between the economic, environmental and social aspects.

References

Borghi, A – Hogain, S – Lewis, J, 2013: Building energy efficiency in European cities. Cities of Tomorrow – Action Today. URBACT II Capitalisation, May 2013 www.urbact.eu

Campbell, S. 1996: Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities? Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. In: Campbell, S. & S. S. Fainstein (2003), Readings in Planning Theory. Second Edition. Blackwell Publishing: Oxford.

Czischke, D – Jonauskis, T – Moloney, C – Scheffler, N – Turcu, C, 2015: Sustainable Regeneration in Urban Areas. URBACT II Capitalisation, May 2015 www.urbact.eu

Cities of Tomorrow. European Commission – DG Regional Policy. January 2011 http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/studies/pdf/citiesoftomorrow/citiesoftomorrow_final.pdf)

Gaffney, A – Huang, V – Maravilla, K – Soubotin, N, 2007: Hammarby Sjostad Case Study | CP 249 Urban Design in Planning. http://www.aeg7.com/assets/publications/hammarby%20sjostad.pdf

Gerőházi, É – Hegedüs, J – Szemző, H – Tosics, I – Tomay, K – Gere, L (2011) The impact of European demographic trends on regional and urban development. Synthesis report. Hungarian Presidency of the Council of the European Union. Budapest, April 2011. www.mri.hu

2015 WS4 Sustainable regeneration (Wilhelmsburg, Hamburg)

Poldermans, C, 2005 Sustainable Urban Development. The Case of Hammarby Sjöstad. Stockholms Universitet http://www.solaripedia.com/files/720.pdf

Rutherford, J, 2013: Hammarby Sjöstad and the rebundling of infrastructure systems in Stockholm. discussion paper for the Chaire Ville seminar, Paris, 12 December 2013. LATTS (Ecole des Ponts ParisTech) http://www.enpc.fr/sites/default/files/files/Rutherford%20Hammarby%20Sj%C3%B6stad%20121213.pdf

Torbianelli, V (ed) Planning tools and planning governance for Urban Growth Management and reusing urban areas. URBACT Use Act First Thematic Paper 2014. www.urbact.eu

Submitted by ivan.tosics on

Submitted by ivan.tosics on