A FOOD WASTE URBAN APPROACH - To reduce the depletion of natural resources, limit environmental impacts, and make the food system more circular

Edited on

09 February 2022Food waste is a serious ethical, social, environmental, and economic problem. It is estimated that one-third of the food produced on the planet ends up in the rubbish bin. If this unsustainable practise was stopped, greenhouse gas emissions would be reduced by around 8% (IFPRI, 2021). Given that this waste is produced throughout the entire food chain, there is a need for consensual, precise, and agile policies that allow all actors to meet the ambitious commitments set by international institutions and states for the upcoming years.

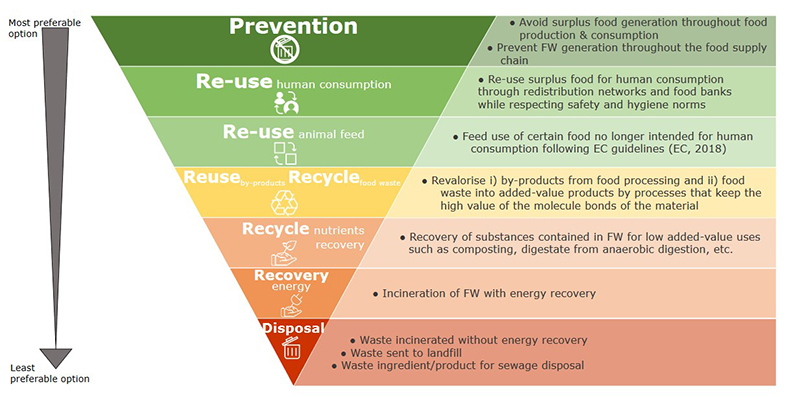

At the European Union level and according to the Sustainable Development Goals, the aim is to halve the volume of food waste generated by 2030, based on a hierarchy of solutions that prioritises prevention, accompanied by reuse, recycling, recovery, and redistribution against abandonment in landfills.

Once again, dealing with an issue of this magnitude and complexity requires specific and local action, and this is where the role of cities and citizens is essential. Together with EU and national policies, city initiatives such as those gathered in MUFPP, Eurocities WFP, and cooperation projects promoted by URBACT, UIA, LIFE, INTERREG or HORIZON 2020 offer knowledge and experiences from which to move forward. Focusing municipal political initiatives on this challenge may represent the necessary boost to encourage local food strategies, due to this issue’s direct connection with the political sphere of municipal intervention.

1. THE PROBLEM

Food waste is a critical factor in the urban ecosystem and represents an essential part of the bio-waste stream. According to the EU Bioeconomy Strategy and the recent Farm to Fork Strategy, food waste leads to the appropriation of natural resources and results in a set of negative environmental externalities, turning urban policy action into a priority.

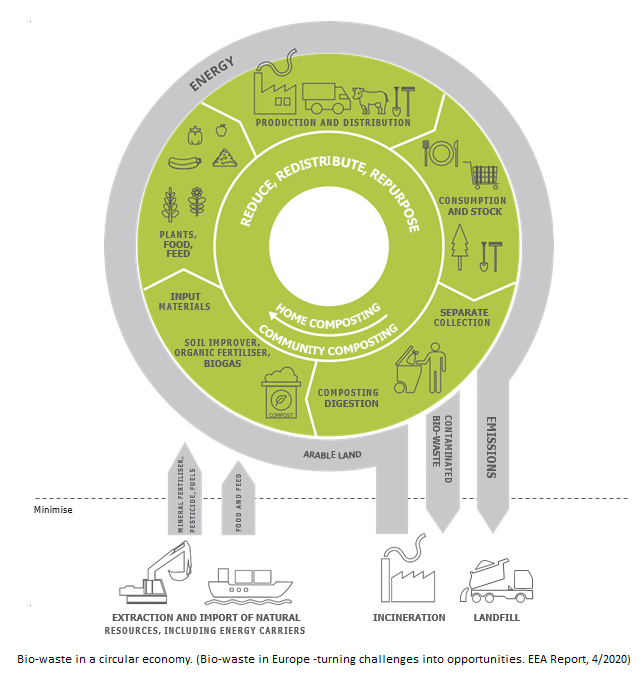

The system's complexity, stages, and elements that make it up are reflected in the following graph (EEA, 2020). It gives rise to a mechanism where the need to reduce extractive practices of limited resources interacts with the urgency of addressing solutions which avoid waste and other negative impact that contribute to the Climate Change effect.

Negative practices occur throughout the whole food chain, from production to consumption. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) appraises that approximately one-third of the edible food produced for human consumption is either lost or wasted globally.

In the context of the EU-28 approximately 20% of all food production is rated to be wasted every year, being responsible for the emissions of 186 million CO2e. The impacts of food waste on climate acidification, together with eutrophication represent 15-16% of the total impact in the food chain. Most of the emissions linked to food waste would be associated with the production phase (cited by EEA, 2020).

In a more local perspective, it is estimated that 38% of the food waste generated in the city of Milan (2019) comes from the production phase, while 42% is generated at the consumption stage. This makes up to €454 the annual economic value of food waste for an Italian household, slightly higher than the average expenditure of a Milanese household on food (€399).

The value of avoidable food waste has been calculated for different EU countries, ranging from €3.2/kg to €6.1/kg. These are reductions that, in economic terms, can represent between €100 and €200/person/year, depending on the country. (EEA, 2020). Different tools have been designed in the European Union or internationally to calculate the value of the food we are wasting, helping to plan various prevention and reduction actions.

2. ACTORS

The international community, through various institutions, the European Union, national and regional governments, cities and all private parties, social organisations and citizens, are active players that must contribute to the development of active policies that strive for sustainable management of food production, based on the principles of prevention, reduction and reuse.

Many policies and programmes have been initiated at state level, such as in the United States through the Save the Food Programme, which invites citizens to be an active part of the solution to avoid wasting 40% of the food produced in the country.

The revised Waste Framework Directive (WFD) (EU,2008, 2018) establishes precise criteria for bio-waste management, forcing states to implement separate collection and recycling by the end of 2023. This is combined with other regulations which promote the reduction of food waste beginning with its correct measurement and monitoring.

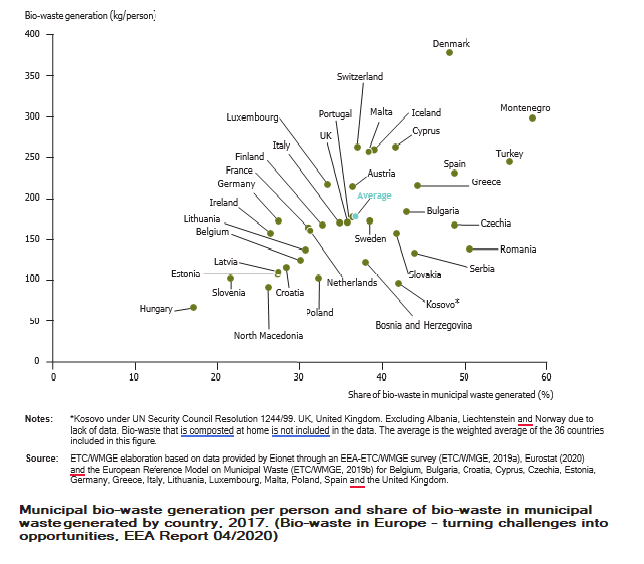

The quantity and quality of bio-waste produced in EU municipalities vary according to the degree of urbanisation, cultural food practices, collection systems, and household composting production, etc., as it can be observed in the attached figure. It gives a clear picture of the magnitude of the problem and how sustainability objectives have its room for improvement in different geographical areas.

The French policy agenda is recognised for its ambition through differentiated actions. Each year the country bears the cost of wasting 10 million tonnes of food worth €16 billion while emitting 15.3 million tonnes of CO2, representing 3% of the country's total emissions. Since 2012 a new national law has been passed to reduce the volume of organic waste disposed of in landfills. At the same time, the private sector (supermarkets, restaurants, etc.) has been obliged not only to reduce their volume of organic waste, but also to recover or reuse it. Various campaigns have been aimed at changing consumer practices, such as the campaign that has involved 120,000 households in Paris to deposit their food waste in a biowaste recycling bin to convert it into fertilizer or facilitate its use for energy production. Simultaneously, numerous private companies participate in initiatives to reduce food waste in their processes and promote circular solutions. Some analyses show beneficial economic results at state, city, and private company levels when effective measures to reduce food losses and food waste are included.

A recent report, DRIVEN TO WASTE: THE GLOBAL IMPACT OF FOOD, LOSS AND WASTE ON FARMS, by WWF (2021), states that "despite this, on-farm food waste remains neglected compared to efforts at the retail and household levels. It's partly due to the complexity of measuring on-farm waste, which makes it difficult to measure progress in reductions and underestimates the importance of its contribution to food waste levels".

Private commercial initiatives are providing innovative solutions to this problem. Packaging-free shops are a direct option to reduce waste in the food chain. Their expansion is visible throughout the EU and very prominent in France and Belgium, with national networks. A report (EUNOMIA,2020) offers encouraging data on the turnover of this sector in the EU by 2030, estimated at between €1.2 and €3.5 billion. Each shop saves 1 tonne of packaging annually, with more than 70% of the products on sale free of packaging and a high percentage of local sourcing.

In addition, it is important to take into account the lack of consumer reaction, especially in developed countries, and what can be done to change this behaviour. Concerning this matter, municipalities, authorities, and companies must have the necessary infrastructure at the service of citizens to facilitate a correct sorting and separation policy for food waste. However, at the same time, citizens do not always have the required conditions at home to carry out this task. They must also find the incentive to commit themselves and get them out of their comfort zone, encouraging their efforts for this social and cultural change, both in reducing and recycling and reusing waste. This is strongly influenced by the context and the characteristics of the different types of citizens regarding their capacities and availability. In general, urban life does not contribute to freeing up the necessary time and facilities required for these tasks, so each city must know the specific barriers to overcome, the target audience to reach, and, therefore, determine the actions to be taken. It is essential to reduce the difficulties and make it easy for residents to participate in these policies. Sometimes it will also be necessary to fight and dismantle preconceived ideas to motivate individual attitudes based on clear and accurate communication.

Many initiatives, from the most generic to the most particular, are in this sense developed by institutions, cities, foundations, and social groups. It is worth highlighting the actions promoted by the FAO, UN WFP, WWF, etc.

3. POLICY LINES OF ACTION

- Food waste prevention

A significant percentage of the food waste fraction is avoidable. Prevention is at the basis of the waste hierarchy established by the Waste Framework Directive (WFD; 2018/851/EC) ahead of other alternatives such as reuse, recycling, recovery, or disposal. This orientation should be matched with the necessary financial support to cover prevention measures. The SDG 12.3 adopted in 2015, commits the EU and member states to halving food waste and losses by 2030.

In order to support all stakeholders in meeting this target, the EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste was established in 2016. A key challenge for states and cities is to correctly monitor and measure food waste, both in terms of quantity and quality, and to ensure consistency to facilitate comparative analyses over time and across territorial and policy areas. Hence, we find different percentages attributed to the various stages of the value chain depending on the sources. In any case, the domestic consumption sector is responsible for generating between 40% and 50% of food waste. In comparison, the other stages of the food value chain account for approximately another 50% between production, processing, distribution, and marketing.

According to some studies (EU FUSIONS, 2016), around 60% of the waste generated by consumers is avoidable. However, this challenge cannot be addressed in isolation at the different stages of the chain. A significant reduction by consumers requires parallel actions by industry, labelling regulations, commercial practices, and packaging.

Once again it is crucial to measure the effectiveness of prevention measures given the uncertainty surrounding the drivers of food waste and the barriers to its reduction, starting by identifying the many gaps in this area of knowledge.

- Biowaste as a relevant focus point

"Bio-waste -mainly food and garden waste- is a key waste stream with a high potential for contributing to a more circular economy, delivering valuable soil-improving material and fertiliser as well as biogas, a source of renewable energy" (EEA Report, 2020). Around 60% of bio-waste is food waste, while bio-waste represents, at 34%, the most significant component of municipal waste in the EU. Progress in recycling is imperative to reach the EU target of recycling 65% of municipal waste by 2035. Moreover, according to the SDGs, the target is to reduce food waste production to 50%.

On the contrary, an efficient separated collection process is needed to reuse food waste as fertilizer and soil improver. Even though benefitting from a noticeable growing during the last years, the percentage of biowaste composted has not even reached the 20%, being the majority of biowaste produced incinerated or landfilled.

Clear criteria about compostable or biodegradable products are also needed, in addition to defined systems to conveniently separate and treat bio-waste fraction and quality standards process to produce compost, digestate, and soil improvers.

Some guides, such as the one created by the Fertile Auro association and published by Zero Waste Europe, guide the collective work to be carried out by those communities that wish to implement composting actions, foreseeing incidents, and recommending key figures such as the master composter.

- Food donation

Redistributing the portion of surplus food production to the more than 800 million hungry people in the world seems an excellent way to alleviate hunger while reducing food waste generation.

However, some barriers hinder this virtuous connection. These include producers' fears about their responsibility for food safety, the cost of transport, the taxes associated with the redistribution process, and the uncertainty and confusion about use-by dates. A study has mapped these obstacles, demonstrating that legislation and policy can positively reduce food waste and food insecurity when adequately aligned with these objectives. Food donation can offer solutions to this critical paradox through win-win policies. The project includes comparative graphs of donations in different countries and a collection of valuable materials to explore this challenge in depth.

In their different versions, Food Banks are the instrument that most frequently intervenes to make this connection possible. This happens in big cities, rural areas, small and medium-sized municipalities, as is the case of Emporio Solidale, an active member of the Local Group of the Unione dei Comuni della Bassa Romagna and an Italian partner of the FOOD CORRIDORS network.

In this sense, food poverty has many hidden faces, and it is present in many individuals and families who are reluctant to go to food banks. However, their diet is insufficient, unhealthy, and unbalanced. That is why many cities are carrying out experiments to address this situation through instruments such as the "family card" in Madrid, the "gift card" in Riga, or by mapping the urban geography of food poverty as Paris is doing to fight against the so-called "food slums."

In short, some critics are concerned about a practice that regularly redirects surplus food to low-income families, a kind of "leftover food for leftover people," instead of developing a specific anti-poverty and social agenda.

4. EXPERIENCES FROM CITIES

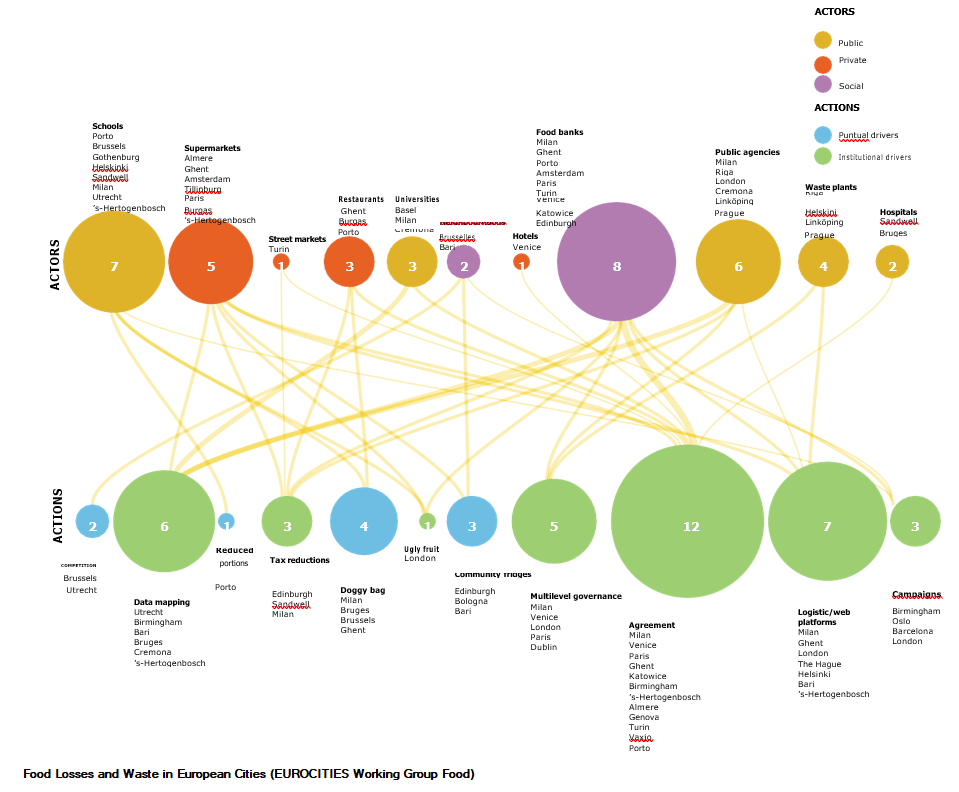

There are many cities that, through different actions, address the problem described here, as exposed at the extensive typology shown in the table below (EUROCITIES WGF, 2018).

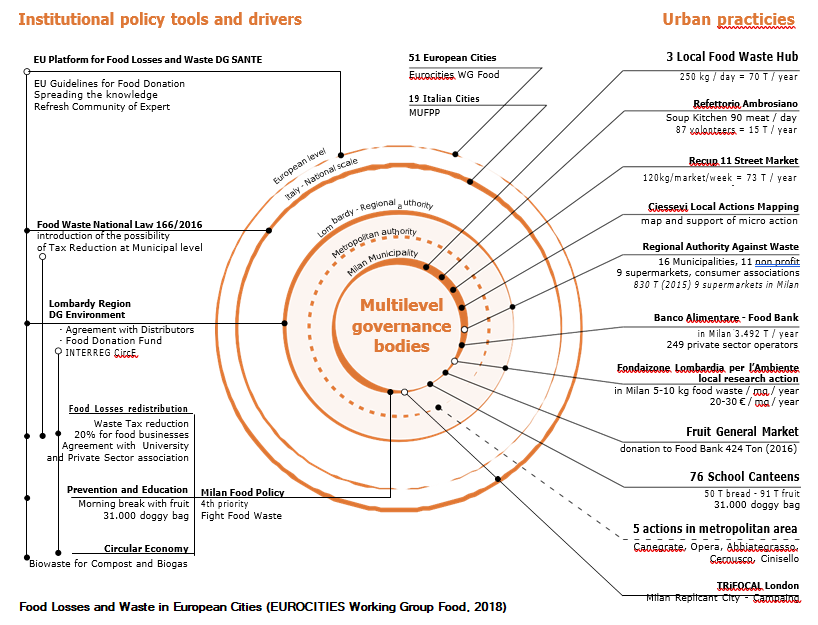

A particular example is the city of Milan which intervenes within its circular economy strategy through 4 axes related to food loss and waste:

1) Promotion of education and information actions.

2) Promotion of the circular economy in the food system.

3) Promoting the recovery and redistribution of food waste by encouraging redistribution through collaboration between actors.

4) Promoting more rational use of packaging.

In practice, the city implements several innovative schemes:

1. 20% Tax reduction for donated food losses

In 2018 the municipality adopted a reduction on the waste tax for food losses donation. This new regulation aims to reduce 20% of the tax for the first year in favour of food businesses (supermarkets, restaurants, canteens, producers, etc.) that donate their food losses to charities.

2. Getting school canteens involved

To reduce the volume of waste associated with fruit served as a dessert in school canteens, an alternative has been designed: "morning break with fruit" which serves fruit as a snack. Other experiments carried out in school canteens have significantly reduced the volume of waste generated thanks to a change of model, as demonstrated by the BIOCANTEENS project.

3. Collection of biowaste for compost and biogas

The city of Milan has an ambitious policy of collecting biowaste to produce compost and biogas. In 2014, 51% of waste has been collected separately (compared to 36.7% in 2012), containing 1.7 kg/person of organic waste per week, or 90 kg/person per year.

4. Local Food Waste Hub

The city has led to an agreement between the University and a private association that brings together supermarkets and companies with canteens to develop a pilot project to redistribute food losses in some of the city's neighbourhoods, with the municipality providing the reception space.

5. A new concept of food market to boost the circular transition

The city of Milan owns a set of 23 covered markets. In the European REFLOW project, a pilot plan is being implemented to offer sustainable solutions to these local markets, aligned with the city's circular economy vision. The project designs and tests logistical solutions, disseminates circular practices, traces the origin and quality of products, and analyses the interaction between rural and urban areas of the territory.

To carry out these and other initiatives, the city of Milan has structured its policies around institutional gearing and different resources, as shown in the following graph (EUROCITIES WGF, 2018).

Other good practices developed by cities such as Athens, Barcelona, Burgas, Ghent, Linköping or Birmingham are detailed in the Guide published by Eurocities and MUFPP, Food Losses and Waste in European Cities.

On another note, innovative initiatives are emerging from the private and social sectors to reuse this food waste, such as BELLA DENTRO, LAST MINUTE SOTTO CASA and REGUSTO in Italy FRUTA FEIA in Portugal, other international ones such as TO GOOD TO GO or OLIO.

5. FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS

The strategy to implement an effective food waste management policy is in line with the fight against Climate Change, while at the same time allowing to address the challenges of Sustainable Development Goals such as 2 (Zero hunger), 3 (Good health and well-being), 12 (Responsible consumption and production) or 13 (Climate Action).

Some actions to support or initiate these policies from cities should be based on some previous facilitators:

1) Measurement. There is no regularised and standardised body of knowledge that provides the necessary data to guide these policies. The more we measure, the better we will know the problem and how to tackle its change. This objective should equally affect different administrative scales (national, regional, or local) and different actors involved in the system (from institutions, business companies, households, etc.) measuring waste and looking for explanations.

2) Raising awareness. We need to understand both individually and collectively why we waste food in this way. Information and education must accompany this process of analysis and design of alternative strategies. Awareness-raising is the main policy option developed by many European Cities.

Love Food, Hate Waste is a successful communication initiative developed by WRAP in the UK. It focusses on people who have already or are looking to take action, providing practical tips and advice. The website offers recipes, advice, and tools, such as the Portion Planner, Food Storage A–Z, and the Chill the Fridge Out temperature checker tool, all of which are making a real difference and influencing people’s behaviour. At the other end of the spectrum, Wasting Food: It's Out Of Date is about motivating those who don't yet know or care about the issue of wasting food.

3) Economic and financial measures. The goal is to reduce food waste through incentives or other market-based instruments such as taxes or subsidies, all of which are seen as valuable instruments to change consumption patterns towards more sustainable practices. For example, in Italy, VAT reductions have been applied to sales of surplus food. In Spain, the city of Gijón, in its Municipal Waste Management Plan, includes the implementation of a tax payment system proportional to the volume of food waste generated, a "pay-as-you-throw" system using information technologies for intelligent data capture.

4) Regulation. Existing legislation and regulations probably need to be adapted to make them more useful and practical for implementation and compliance by the multiple private actors, taking care and protecting the public good of food.

In a similar way, companies in the food sector, at their different stages, should be clearly aware of and benefit from economic profits associated to a reduction of losses and spills along the value chain.

In countries such as the Czech Republic, France, Italy or Poland, progress has been made in recent years in banning the destruction of unsold food, forcing its redistribution via donations or use for composting together with other solutions in line with the European hierarchy of food surplus management. Often, voluntary agreements between parties can replace regulatory measures.

In addition, certification and labelling initiatives can be an excellent incentive to carry out food waste monitoring and reduction measures by the parties involved, especially companies. They can also be an essential element to be considered in public procurement actions by institutions. In Denmark, a public-private-social partnership has created the ReFood Label, which functions as a green label and recognises organisations and companies active in reducing food waste.

Finally, clarification of date labelling should be an effective regulatory instrument in the relationship between production, distribution, and consumption. In Norway, a positive example has been set with the inclusion of a stamp on the packaging of eggs by one producer stating "best before, but not bad after" to combat food waste.

5) Plans and projects. In a balanced way, the development of projects should follow the EU food waste hierarchy's logic, prioritising the objectives linked to prevention and reduction actions, guaranteeing the adequate availability of resources, generally oriented towards investments in infrastructures, installations, and treatment equipment.

As some are already demonstrating, cities must be key policy partners in addressing food waste in an integrated way. For this, they need adequate funding from states and other transnational bodies. In addition to prevention and reduction, two areas of waste management require special attention because of their co-benefits. First, by encouraging solutions based on composting and digestate where training and pilot projects can be of great help. And secondly, with the intensification of social and economic crises that impoverish large sections of the population, promoting policies for the collection and redistribution of loss and food waste. In this case, collaboration with the production, processing and marketing sector must be combined with the participation of social initiatives that have been set up, many of them thanks to the support of European projects and almost always with an important technological base and digital presence.

Through these pilot plans and actions, cities can set specific food waste reduction targets, in line with SDG 12.3.

6) Stakeholder participation. Both individual and collective, participatory-based solutions need to be promoted, including incentives for good practice. Many redistribution platforms are based on collaborative arrangements involving retailers and catering companies with volunteer groups, NGOs, and institutions. The impact is visible and easy to monitor, although it must be ensured that the necessary resources are available to guarantee the storage or delivery of fresh produce.

A good guide of activities to start preventing waste food is proposed by the British non-profit organisation WRAP, including precise recommendations to initiate prevention, planning, behavioural change, communication, etc.

This article has been written in parallel to the process of designing Integrated Action Plans by the partner cities of the FOOD CORRIDORS network. It is intended to provide information to inspire their proposals for action. A more practical version of these contents will be tested in transnational workshops of the network. Further articles will be published in the coming months in line with the FOOD CORRIDORS theme described in the Baseline Study of the Project.

* Antonio Zafra is the Lead Expert of the FOOD CORRIDORS network

* Antonio Zafra is the Lead Expert of the FOOD CORRIDORS network

By the same author: "Closing loops in local food systems" (URBACT, 2021).

Submitted by Vera Lopes on

Submitted by Vera Lopes on