We need to talk about smart specialisation!

Edited on

09 October 2017Why cities need a stronger role in smart specialisation to drive innovation in Cohesion Policy

Innovation in Cohesion policy has gone from four pilots in 1994 to being ex-ante conditionality in the 2014-20 regulations. This is like going from the wild fringes to being at the centre of policy. It is thought likely that this programme period has more than the 85 Billion Euros that were dedicated to Innovation in the 2006-13 periods making up 25% of the Structural Funds.

As defined in the smart specialisation guidance and only hinted at in the ERDF regulation: “a ‘Smart specialisation strategy’ means the national or regional innovation strategies which set priorities in order to build competitive advantage by developing and matching research and innovation own strengths to business needs in order to address emerging opportunities and market developments in a coherent manner, while avoiding duplication and fragmentation of efforts…. Smart specialisation strategies shall be developed through involving national or regional managing authorities and stakeholders such as universities and other higher education institutions, industry and social partners in an entrepreneurial discovery process.”

It is evident that cities, and more particularly metropolitan areas, are the public sector drivers for smart specialisation. Cities are the motor of the European economy responsible for more than two thirds of GDP. In addition, urban areas are the location of most of the research centres and Universities and of the vast majority of non-agricultural SMEs. It is in cities that the main investments in incubators, spinouts and start-up support is made. Cities offer the greatest potential to exploit the opportunities presented by smart specialisation strategies and funding from the Structural Funds. But metropolitan governance is still patchy across the Union and the adage ‘21st Century economy, 20th Century administration 19th Century boundaries’ still holds true for many cities.

Non Fractal regions and cities

If regions were fractal, a mathematical set that exhibits a repeating pattern that displays at every scale, (see Figure 1 on the right) it would be possible to go down the urban hierarchy and find at each level the same proportion of sectors and key technologies and similar partners.

However, cities are not mere fractal reflections of their regions. Each city has its own specialisms that may or may not align with those determined at regional level. This is true for both small and large regions and for small and large cities. It means that in practice some of the clusters identified at regional level will not be relevant for a particular city. Other local clusters that may be a key part of the city’s local economy will not be relevant at regional level. This mismatch affects the city economy because it may restrict funding opportunities from Structural Funds that are cluster focused. Of course these cities are the ones that most need support from cohesion policy to shift their local economies into a new place.

However, cities are not mere fractal reflections of their regions. Each city has its own specialisms that may or may not align with those determined at regional level. This is true for both small and large regions and for small and large cities. It means that in practice some of the clusters identified at regional level will not be relevant for a particular city. Other local clusters that may be a key part of the city’s local economy will not be relevant at regional level. This mismatch affects the city economy because it may restrict funding opportunities from Structural Funds that are cluster focused. Of course these cities are the ones that most need support from cohesion policy to shift their local economies into a new place.

Figure 1:In a fractal the deeper you go the more it stays the same - Mandelbrot set. Source Wikipedia

Alfred Marshall was one of the first economists to write about industrial districts in 1919. He emphasised the cooperative aspects between companies in such districts that were mutually inter-dependent. He showed how the city operated both with a specialised division of labour between firms and with supportive infrastructure. He characterised it as a factory without walls for the production of certain items such as a knife made in Sheffield which went through numerous neigh bouring factories before being wrapped and sold. In modern economies the relationships have changed although it seems likely that propinquity, or closeness is still a feature in enterprise ecosystems and when we survey the European start-up scene we find that it is often particular neighbourhoods in a limited number of cities that are relevant for key types of start-up such as those in tech and coding. Relatively little research has been published about the micro-geographies of these clusters but it is reasonable to suppose that proximity and social networks play a part in their genesis.

Other forces play a role. The abandonment of parts of cities by older trades often creates new opportunities for young creatives. Where creatives go, coders and other start-ups follow, often enjoying the edginess of these transition areas. However, over time property values rise, gentrification starts to squeeze out the enterprises. The rise of these areas usually happens outside of or despite the planning system. Once established, planning rarely does enough to protect them.

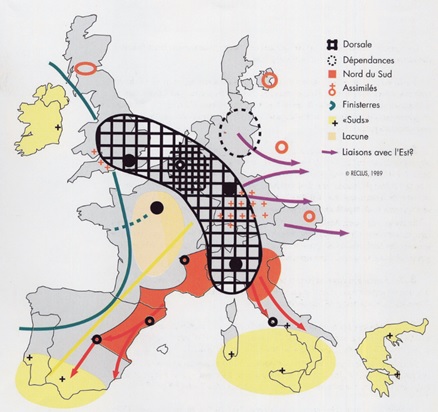

But EU innovation is heavily concentrated in the higher end of the urban hierarchy and in the ‘Blue Banana’ which extends from London, Manchester and Birmingham to Milan and Turin in Italy. This is particularly true for research projects financed under each generation of the EU Framework Programme. Despite two decades of effort by cohesion policy support, getting an innovation culture to flourish outside the banana has proved difficult and especially in smaller urban and more sparsely populated areas.

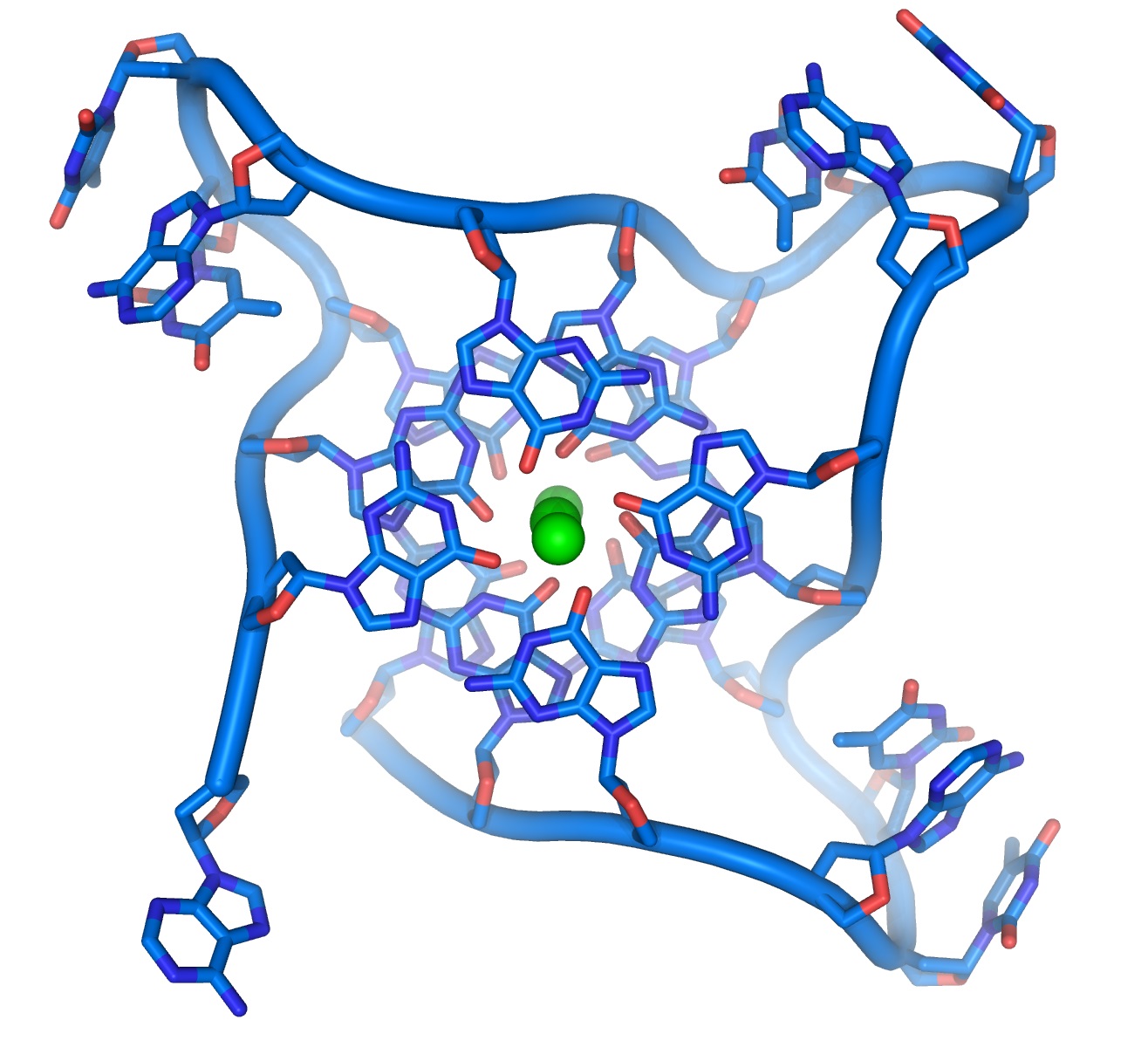

A key element of successful innovation policy for both cities and regions is the concept of the triple and quadruple helix.

A key element of successful innovation policy for both cities and regions is the concept of the triple and quadruple helix.

Successful triple helices have dense interactions between small and medium sized enterprises and the research infrastructures of the area. These are facilitated and supported by the public sector, often through the setting up of arms-length development agencies such as Brainport in Eindhoven, a lead partner in URBACT network CHANGE. The quadruple helix takes this a stage further by engaging actors from civil society in the development of new products and processes. This is both important for testing new products and for co-producing, co-designing and co-creating new services. There is a strong overlap with the Living Lab movement which offers the city and its communities as test areas for new developments. URBACT has worked extensively on issues around business-research links including in networks REDIS led by Magdeburg and eUniversities led by Delft. Good practice examples of triple helices were high

lighted in the recent URBACT New Economies publication which referenced Eindhoven, Dublin and San Sebastian.

Figure 2: The Blue Banana in Europe source Reclus 1989

Smart specialisation, cities and URBACT

Smart specialisation, cities and URBACT

Despite the potential offered by the resources available from Smart Specialisation focused priorities[1] in the new Structural Fund Operational Programmes, anecdotal evidence from the ten cities[2] of the URBACT In Focus network suggests that cities have often been excluded from the discussion. This exacerbates the risk of mismatch between regional strategies and what is happening in the cities. The process of ‘entrepreneurial discovery’ that is supposed to inform the discussion of emerging sectors and technologies has often been superficial and according to Miguel Rivas Lead Expert of the network did not sufficiently involve the urban actors. The result is that too many of the Smart Specialisation strategies are sitting on a shelf. It will need cities to bring them to life.

In Fcous is addressing these questions about how cities can benefit from and drive regional smart specialisation strategies and has sub themes on clusters, entrepreneurship, new spaces, and branding/ attractiveness. The network includes major technological cities such as Bilbao, Porto, Bordeaux, Grenoble, Torino and Frankfurt. Each of these has many cluster opportunities to choose from ranging from financial services in Frankfurt to Optoelectronics in Bordeaux. The network also includes cities in regions that are focusing on innovation but without so many assets and in regions with lower levels of development including Plasencia in Extre Madura, Bielsko Biala in Poland and part of Bucharest.

In addition, URBACT network Smart Impact, led by Manchester, is exploring the question of how smart districts can be developed within the burgeoning brand of Smart Cities. Often these districts will be the locus for new collaborations between research and industry and the test beds for new products and services.

Cities all over Europe can learn how better to be engaged with the smart specialisation process. Even if they missed out in the drafting of this generation of strategies there will be opportunities to influence the next generation. Most importantly, they need to understand the process and the opportunities that the strategies present. Cities in every region should be reading their region’s smart specialisation strategy and operational programmes, making contact with the Managing Authorities and drawing up local plans for projects to promote innovation. URBACT will be publishing sessons for cities about how they can be both smart and more specialised to inform the debate and build know-how.

Figure 3: A DNA quadruple helix source: source Huffington Post

Acknowledgement: This article draws on the baseline study carried out by URBACT expert Miguel Rivas for IN FOCUS a network led by Bilbao. It is anticipated that the baseline will be published in July. All comments expressed here are those of the author.

[1] Typically this is under Thematic Objective 1 of ERDF for Innovation.

[2] See Miguel Rivas 2016 In Focus: Smart specialisation at city level Baseline Report URBACT Forthcoming

Submitted by Peter Ramsden on

Submitted by Peter Ramsden on