URBAN MAPPING: MURCIA COLLECTIVE CARTOGRAPHY IN SANTA EULALIA PART 1

Edited on

02 October 20181. INTRODUCTION

This article (divided into two parts and therefore publications) wants to reflect those issues that have led us to select, and use, collective urban mapping as a primary tool during the process of citizen participation. We understand the result of each urban mapping as a new cartography, a graphic document based on the mapping of the selected work area – the Santa Eulalia neighbourhood - that combines, collects and spatially places all aspects the participating neighbours believe to be vital or of greatest relevance for improving the living conditions and urban quality of their neighbourhood.

The way we have structured the article includes detailing the different age groups or groups we have worked with, the general methodology applied, the conclusions reached and the risks or deficiencies that we have detected in the use of this analytical tool during the process. The conclusions commented here are not the result we will reach after the superposition and filtering of the different mappings, but will focus on the capacity of this tool, which allows us to extract valuable data that can be extracted and applied to enrich proposals and interventions in urban areas.

In this first article we will focus on the information regarding the mapping of people with physical and organic disabilities, elderly people and children, the second article focuses on the mapping of the rest of groups and the results obtained in both cases.

|

2. BACKGROUND

Knowing the historical use of mapping as a potential tool in urban design, and an analysis of its current use by different national and international professionals (Urban Ecosystem, Transverse landscape, etc.) as well as its use decades ago, for example by Anna and Lawrence Halprin (60s), dancer and architect who some authors cite as the pioneers of the participation in processes called "take part", or in other words, processes that have citizens participate in the design of their environment.

Also, in this first analysis that would serve as a base to start the urban mapping, we also reviewed authors we consider to be of interest here in Verbo estudio, like the psychologist and Italian cartoonist Francesco Tonucci, or the architect and painter Aldo Van Eyck, both because of their masterful work and investigation taking children as primary actors in the conformation of the city and its urban spaces, reminding us of the playful quality these spaces have.

In view of these references, we can start to understand the context in which we are situated - the Santa Eulalia neighbourhood - and after the analysis of the document "Physical study of the area as a whole", which made us aware of the physical aspects of the neighbourhood, we began by selecting the methodology to be used.

|

3. METHODOLOGY

First, we selected the groups with whom we were going to work. It is important to note that the choice of groups is not to exclude other collectives, although there has been a selection in which we ranked by the representation of each group in the neighbourhood, so to underline the inclusive and plural aspect of the process, parallel to the group mapping we are conducting surveys and implementing other ways of participation which are plural and open to any citizen.

Given the heterogeneity of the different working groups, we decided to use different methodologies with each one of them. In general, the tools used during the process are drawing, participatory cartography, stickers, conversations and debates, etc. of which the results are recorded and spatially placed on a large-scale map of the neighbourhood.

|

Work groups:

1. People with physical and organic disabilities

2. Elderly people (>75 years of age)

3. Children (8-11 years of age)

4. (Young) University students

5. Owners of bars which have terraces in the squares of the neighbourhood

GROUPS 1 & 2: People with physical and organic disabilities and elderly citizens

In these first two groups the methodology used is identical, starting the first phase of the activity with a walk through the neighbourhood that allows us to uncover the first concerns and suggestions of the collective’s attendees, recorded and collected at any time throughout the visit and maintained conversations. A modifiable route which can be readjusted at any time if the need arises through suggestions and recommendations, enriching it with direct input from the participants.

The aspects to be dealt with during the route of the walk (for example: inaccessible spaces, obstacles, lack of green spaces and plants, narrow streets, etc.) are given as a starting point that is progressively extended and allows us to focus on those issues that most concern the collective, and that can for a bases for the subsequent mapping.

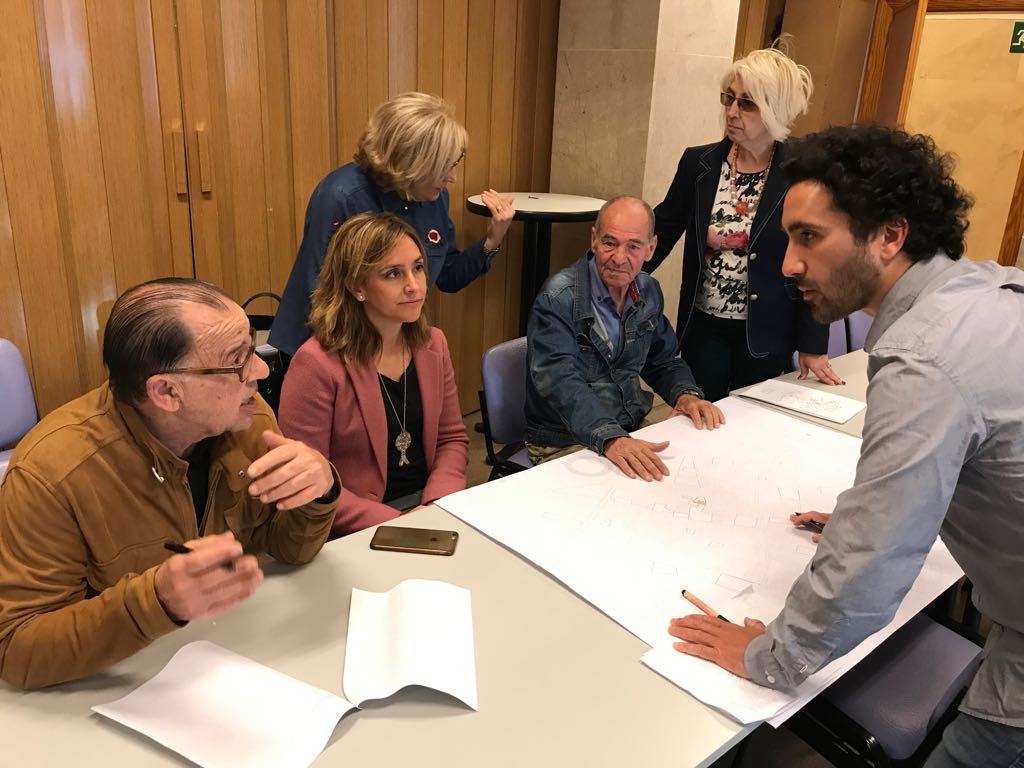

After establishing this first contact with the neighbours by means of a group walk, a meeting is held with a large-scale map of the neighbourhood in which the attendees spatially place and physically connect all the necessities that have been identified during the walk, adding more contributions and opinions in the conversations and debates during the meeting itself. In this part of the process it is important to rank the identified necessities so we know which are most urgent or most frequently requested.

As a result of the meeting, the cartography allows us to identify areas and potential improvement points that allow the development of proposals.

|

GROUP 3: Children

With children we decided to take a free approach through exercises, rather than following the same strategy as with other groups. In the first phase of the activity, the youngest children were asked to draw the route they take from home to school, and letting their imagination flow in order to detect which urban elements were the ones that attracted their attention, whilst also asking "what other things would you like to have?" so we could detect what demands and concerns the youngest of our neighbours have.

In the way we understand the strategy we followed with the children, the activities required to be completed with others of a more visual nature, in this case a tour of the neighbourhood in which they were asked to give their opinion on different aspects and where we could detect their demands.

Some notable aspects of the result are the numerous references to shops - with the name of the written trade - but a lack of references to specific urban spaces, as the children only identified the square where the activity took place as a “playing space” in the entire neighbourhood. This leads us to believe that, in the perception of the youngest, there are few spaces they perceive as “playing spaces” or spaces where they can have fun, which tells us that it is a neighbourhood that has great room for improvement in these aspects. Additionally, we noted that in the neighbourhood has a young population that have small/young children, and an elderly population, which highlights the need for shared spaces where different age groups come together even more.

This article continues in URBAN MAPPING: COLLECTIVE CARTOGRAPHY IN SANTA EULALIA PART 2

AUTHORS

Dictinio de Castillo-Elejabeytia Gómez, Carlos Pérez Armenteros

VERBO Estudio (April 2017)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Koolhaas, Rem. “La ciudad genérica”. Ed. Gustavo Gili, S.L, Barcelona, 2006.

- Augé, Marc. “Los no lugares”. Ed. Gedisa, S.A, Barcelona 1998.

- Cano Clares, José Luis. “Plan general de Murcia de 1978”. Ed. Diego Marín, Murcia, 2005.

- Cano Clares, José Luis . ”Ciudades. El arte urbano”. Ed. Diego Marín, Murcia, 1999.

- Vinuesa Angulo, Julio. “El festín de la vivienda”. Ed. Díaz &Pons S.L, Madrid, 2013.

- Alarcón, Tomás. “Murcia Antigua en fotografías”. Tipografía Guirao, Murcia, 1985.

- Gehl, Jan. “La humanización del espacio urbano”. Ed.Reverté, S.A, Barcelona, 2006.

- Museo nacional Reina Sofía. “Playgrounds: reinventar la plaza”. Ed.Siruela, S.A, Madrid 2014.

-Jacobs, Jane. “Muerte y vida de las grandes ciudades”. Ed.Capitan Swing, Madrid 2011.

-Tonucci, Francesco. “La ciudad de los niños”. Ed. Graó, Barcelona 2015

ARTICLES

-García Pérez, Eva. “Ciudad árbol, ciudad Flexible y ciudad No Subjetiva”. Ed. Urgente, no.7, Madrid 2005.

-Barba, José Juan. “Genereic and Queer city”. Ed. Formas, no.17, Madrid, 2007.

-Barba, José Juan “La ciudad contemporánea”. Sp. Illuminosis*en el espacio público, 2013.

-Alexander, Christopher. “La ciudad no es un árbol”. Berkeley, 1965.

Submitted by fvirgilio on