THREE-PRONGED APPROACH TO SUCCESSFUL REGENERATION

Edited on

07 June 2019The way to achieve social mix in historical areas of cities.

1. The Remixers network situation

The Urban Regeneration Mix partner cities[1] have already worked together in two transnational seminars and have created a unified group ofengaged specialists, have agreed on the main themes of this URBACT transfer network, and have produced the first versions of their Transfer Plans, an obligatory part of the transfer network journey planned by URBACT. The three essential elements on which the network will work are: mediation, public-private partnerships and regeneration management.

2. 17 UN goals, EU Urban Agenda

Many things are evolving worldwide and in the European Union concerning urban policy and the importance which it is gaining. As is well known in September 2015, all 193 members of the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2030 Agenda), committing themselves to specific actions towards, among others, eliminating poverty, ensuring peace, well-being and protecting our planet. As one of the key goals, the 2030 Agenda recognizes the sustainable urban development (SDG 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable).

What is important to underline, is that not one of these 17 SDG’s can be achieved without the others. Therefore the 2030 Agenda of the UN clearly shows the need for clearly positioned cross-cutting urban policies, in order to achieve positive results in such key areas as urban mobility, environmental protection, energy, climate, investment and many more. The same applies to regeneration policies, which involve most of the above themes.

In addition, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme UN-Habitat adopted the New Urban Agenda, during the Habitat III Conference in Quito, in October 2016. This document draws attention to the challenges of the progressing urbanization and suggests possible courses of action, thus reinforcing the 2030 Agenda mission to support sustainable urbanization.

Source: International Science Council: SDGs Guide to Interactions, 2018

At the European Union level, it was the Dutch presidency which launched the EU Urban Agenda, with, at present 14 themes[2] relating to urban policies. These themes, worked through by governments, cities, European wide institutions and associations and the Commission have shown the example in horizontal working at different levels, of the need for all stakeholders to be present and participate in defining cross-cutting policies.

The EU Urban Agenda has given the example in what could be termed as holistic and horizontal management, cutting across the habitual institutional lines and showing the way for cities, regions and central governments to abandon their very “silos” type of management, in favour of more open and interdepartmental collective decision making.

3. Contributions from research

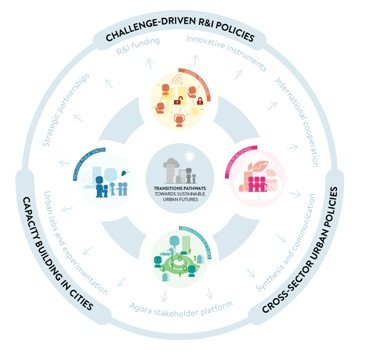

From the research side two major reports have come into being, one from the Joint Programming Initiative[3] (JPI) Urban Europe, and the other from the Joint Research Centre[4] (JRC). JRC is finishing a report called “Future of Cities Report” which will be a serious contribution to the territorial and urban knowledge base in Europe. JPI Urban Europe has already presented its SRIA 2.0 report in early 2019.

JRC presents its findings by analysing the challenges and perspectives of urban policy. It conceptualises the provision of services, social segregation, mobility, water, health, housing, ageing, the urban footprint, and climate action, as the Challenges series. On the other hand, the Report sections on public space, citizen engagement, technology, innovation, resilience, and governance are subsumed under a Perspectives approach focusing on the added value of cities.

On the other hand, JPI Urban Europe presents a dilemma-based perspective: The Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda (SRIA) report defines “an urban dilemma as two or more competing goals, such as stakeholder interests and related strategies which potentially fail to achieve their aims as implementing one strategy hampers or prevents the achievement of another”. The SRIA underlines the importance of the dilemma-driven approach “to simultaneously connect between sectors and silos to shape communication lines, support or generate traction where it is needed, and the ‘bite-sized chunks’ of complexity that are required entry points to tackle wicked urban issues”. Examples of these dilemmas are:

From resilience to Urban Robustness[5]:

How can cities get prepared for unexpected, non-linear events and at the same time ensure highest liveability for its inhabitants?

Digital transitions and urban governance:

How can cities exploit the potential of rapid digitalisation for urban planning and governance while avoiding the risks of new inequalities and exclusion as well as addressing the consequences for jobs, value chains and privacy?

Sustainable Land Use and Urban Infrastructures:

How can cities answer the demand for densification and infrastructure provision under the constraints of scare resources, financial limitations, accessibility and affordability for all?

Inclusive Urban Public Spaces:

How can cities provide multi-functional public spaces that serve the purposes of all groups of society within the given ownership situations, stakeholder interests, security concerns or densification needs?

Source: JPI Urban Europe.

The above diagram shows SDG 11 as the entry point for sustainable urban development targets. Some goals and targets have conflictual relationships. Understanding potential synergies and trade-offs is critical for efficient and coherent implementation and monitoring which shows the need to develop a holistic approach to drive system change[6].

4. How to improve the regeneration practices?

The above aims, processes and analyses show the increasing complexity of urban policies. In Urban Regeneration Mix, we have to take stock of all these elements, reducing them to a minimum in order to try to improve what is being done on the ground.

The Lodz Good Practice is working on social mix in the given area (including mix of populations, activities, types of infrastructure etc) as well as developing the quality of life in a historical city centre. In Birmingham the city is confronted with new developments neighbouring older, much poorer ones, Bologna needs to fill a gap in the participation in cultural infrastructure of the local inhabitants, while Braga is working on a participative model of decision making for all urban policy matters. Zagreb and the Toulouse Metropolitan Area are both working on a brownfield, which must become an integral part of the city taking into consideration what local residents want and feel, while Baena is looking to secure a more balanced city life between the older and newer parts of the city.

These challenges, shown in short, correspond exactly to the mainstream thinking about urban policy discussed in the earlier paragraphs. The Urban Regeneration Mix partner cities will be working in a cross-fertilisation way on three main themes, in order to try to improve the partner city practices, not only by transferring some of the experiences of the lead partner Lodz, but also by interchanging their mutual experiences.

5. The three main themes

5.1 Mediation

Lodz has brought into the regeneration transfer its practical experience in bringing the inhabitants into closer connection with the city authorities. These mediation techniques developed on the basis of a need to support the displacement of residents of properties selected for regeneration, are now fast becoming a quality service which, the city has to enrich, as repopulating the emptied tenement buildings will require a whole intricate system of management and empowerment-based relations with the residents. This new approach is stimulated by the Toulouse Métropole system of project managers, who have a facilitated access to the highest decision-making instances, and have a very wide scope of responsibilities. On the other hand, Braga is developing a city-wide notion of participation in urban policies, steering away, for the time being, from the difficult 3 areas inhabited mainly by Roma populations, so as to involve the whole city in urban decision making.

This mediation theme is very necessary in Bologna Metropolitan Area, where bringing the citizens into the cultural infrastructures appears as the main challenge, but requires enriching, as these infrastructures want to open up in a permanent fashion not only to the residents living close, but to the whole population of the metropolitan area. In Birmingham the austerity policies have reduced all forms of paid mediation to zero, but in the area concerned, the city, in partnership with local residents and associations, is working hard to put into place what is called a “localism policy” opening up the city to the voice and co-decision making of residents.

However, the improvement of regeneration policies is not solely dependent on the very necessary contact and confidence with residents. Other vectors are the availability of financial resources and appropriate decision-making processes.

5.2 Private Public Partnership

Not only Birmingham is confronted with financial dilemmas, as to how best to spend generally shrinking public budgets. The partner cities all agree, that the possible partnerships with the private sector constitute one of the rare ways, where there is any light in the tunnel. Here if Lodz and Birmingham have some experiences, its Toulouse Metropole which appears as the specialist in this area, and the future Transnational Workshop in this city will be mainly devoted to this subject. As the representative of the Croatian Ministry of Economy Domagoj Dodig said in Zagreb, PPP are simple, but they require a certain train of thought, as well as specific high-level engineering processes, which are transparent and clear to all. What is most important is to understand, that PPP allows a different mode of functioning, as the private sector is contractually bound to share several of the risks, especially on operational issues, where more often than not, it has more experience than the public sector.

It is the hope of all the partner cities to find ways of improving their financial availability, in order to be able to finance different projects, including brownfields. An ancient industrial area, which is often in the centre of a city, requires a high level of investment, to make it become “part of the city again” and to permit housing, or collective public spaces to be created.

5.3 New ways of management and decision-making processes

Relations with residents and new financial resources imply, that the decision-making processes inside cities, but also with their regions and national governments, will be capable of considering these new realities. The Urban Regeneration Mix network does not yet have a particular model of city management to transfer to the partner cities, but it is hoped that work on the two above themes will progressively develop a number of elements, which will facilitate this type of process. Already at this point the network realises that:

Mediators have to be empowered in a permanent way, if they are to be respected and seen to be efficient in their work with residents,

The interactions between face to face work, intermediate and higher management has to follow new rules, in order to guarantee very much needed cohesion at all levels,

New financial resources can mean changing ways of thinking and decision-making processes. This requires a high capacity of collective learning and acceptation of a collective theory of change, in order for a change to be acceptable to a majority of stakeholders,

These new ways of working regeneration may require senior politicians as well as higher management to cede some of their decision-making powers to lower echelons, in order to maintain the empowerment-based relations with inhabitants,

The question of impact management will also have to be addressed in order to try to check if applied policies are giving the expected results.

6. Pre-conclusions

It is hoped that the experiences of the lead partner Lodz, and of the network members will allow the transfer process to progress. It will be very interesting to see how and why certain elements of the regeneration policies will be received and applied in the network cities, and maybe even further. However, at this point in time, the collective learning of the network is still progressing, and the transfer processes, as described in the Transfer Plans, will be verified by the Urbact Local Groups (ULG) as they confront them with the local realities, and also the capacity which each city has to reflect on its principles and methods to produce change.

Footnotes

[1] Baena (ES), Birmingham (UK), Bologna Metropolitan Area (IT), Braga (P), Toulouse Metropolitan Area (FR), Zagreb (HR) and lead partner Lodz (PL).

[2] Culture/Cultural Heritage, Security in Public Spaces, Sustainable Land Use and Nature Based Solutions, Public Procurement, Energy Transition, Climate Adaptation, Urban Mobility, Digital Transition, Circular economy, Jobs and Skills in the Local Economy, Urban Poverty, Inclusion of Migrants and Refugees, Housing and Air Quality.

[3] https://jpi-urbaneurope.eu/app/uploads/2019/02/SRIA2.0.pdf

[4] https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en

[5] Whereas resilience denotes the capacity to recover, robustness focuses on the sturdy and healthy ‘baseline’ of urban settings as a pre-condition for sustainability as well as for sound resilience in crisis-management.

[6] JPI Urban Europe as presented at the preparatory workshop of the German presidency on the new Leipzig Charter.

Submitted by n.rydlewska on