A Tale of Two Cities. Transfer Stories from East and West.

Edited on

07 June 2021Two German cities are currently lead partners in the 23 URBACT Transfer Networks. Altena in North Rhine-Westphalia and Chemnitz in Saxony. Altena shared its best practices on how to develop sustainable initiatives with a minimum of external resource input in the Re-growCity network. Chemnitz shared its good practice of activating vacant buildings in need of refurbishment in the ALT/BAU Network.

Both cities were forced to develop methods to lessen the impact of the severe population loss. Chemnitz, in the east, lost about 25% of its population after German reunification until 2005, most of whom migrated to the west to find employment. Altena, in the west, has been losing residents since the 1970s. Between 1990 and 2009, the city was subject to a 15% population decline, making it the municipality with the fastest population decline in NRW. How did the two cities experience the transfer process in the URBACT networks over the past two and a half years? Volker Tzschucke, ULG member in Chemnitz reports about both cities.

Two cities exploring Europe

At first glance, Chemnitz and Altena don't have much in common. Chemnitz, Saxony's third-largest city with just under 250,000 inhabitants, offers plenty of space: socialist wide streets, large parks and squares and car parks. Altena, with 18,000 inhabitants, is located in the Märkischer Kreis in North Rhine-Westphalia and presents a face that a model railway enthusiast would dream of: a river in the valley, railway tracks beside it. On the ridges along the river on one side proud villas and on the other a historic old town that winds its way up to the soon to be 1,000-year-old castle on the hilltop.

Pure contrasts - medieval town in Altena, socialist architectural style in Chemnitz also known as Karl-Marx-Stadt. Photos by G. Schmitz, S. Hausmann

At second glance, the cities are more similar: both with a formative industrial past. Both with "15 minutes of fame" in recent years, but of the kind that one would have liked to do without: Altena attracted attention throughout Germany because its mayor Andreas Hollstein was attacked with a knife in a kebab snack bar in 2017: The perpetrator was dissatisfied with the refugee work of the local politician, who also wanted to do something against the ageing of his town by taking in an above-average number of refugees.

In Chemnitz, such dissatisfaction manifested itself in the course of the refugee crisis in 2018, when the city became a parade ground for right-wing radicals from all over Germany. Chemnitz is also ageing and losing inhabitants step by step. In both cities, population development leads to high vacancy rates in residential buildings or in shop spaces, which are all too often left to themselves and thus to decay. But in both cities these developments were recognised several years ago and steps were taken to counteract them - such good and successful steps that they were recognised by the European Union as exemplary: Both Altena and Chemnitz were therefore invited to pass on their experiences to other cities within the framework of the EU's URBACT programme, which deals with urban development issues.

Altena did this in the URBACT Transfer Network Re-growCity. Altena's transfer story can be read here.

The challenge of empty buildings

Like Altena, Chemnitz led and still leads such a network. Here it was the project "Agentur Stadtwohnen Chemnitz" (Housing Agency) that was seen as particularly worthy of emulation: In view of the numerous vacant old buildings in districts such as Sonnenberg, Schlosschemnitz or Brühl-Quartier, the city administration had set out to tackle the problem in a targeted manner. A coordination office should first catalogue the vacant buildings, contact the owners, encourage them to think about new models of use and inform them about available funding opportunities. Or support a change of ownership into good hands. In 2011, the Westsächsische Gesellschaft für Stadterneuerung (WGS) was entrusted with these tasks by the City of Chemnitz, which has since taken care(ed) of far more than 100 buildings in the particularly affected districts. "This is an important development for Chemnitz," says Grit Stillger, Head of the Urban Renewal Department in the Chemnitz city planning office: "The buildings under consideration are formative for the cityscape, but also for the mood and spirit in Chemnitz. Because they tell a lot about the past development of the city, for many residents they also symbolise the future development of the city." So it's all the better if they tell of people who see their future in the city - or have so much faith in Chemnitz' future that it's worth investing in bricks.

The agency's structured approach yielded some successes: dozens of the houses observed are now completely renovated and being used anew or are in the process of renovation. The idea of also telling Europe about it was obvious: "In the end, the WGS suggested proposing the Housing Agency model for the EU's URBACT programme," says Grit Stillger. In 2017, it was recognised as good practice and Chemnitz was allowed to form a European city network as a lead partner - with six other partners facing similar challenges, including the Latvian capital Riga and the former Olympic city of Turin.

Passing on and learning for yourself - Share knowledge and learn something yourself

In the past two years, the Chemnitz partner cities explored in several workshops, during city explorations and in interaction with local actors how they could set up their own "Agentur StadtWohnen Chemnitz", tailored to local real estate markets, but also different administrative structures or tax systems. For Chemnitz as the lead partner, the networking was different: "On the one hand, we chose the partner cities so that we could also learn something from their projects on dealing with old buildings," reports Dr. Frank Feuerbach, who coordinated the local URBACT work as an employee of the city administration: "And on the other hand, we could discuss whether there was a need for further development in our work. The approach was quite open-ended: Does the agency still need to exist in this form? Should it focus on other districts, expand its work to other types of real estate - for example brownfields? All this was discussed, always also on the basis of the experiences in the partner cities: "For me, for example, it was inspiring how continuously Riga works on the topic of interim use of unused real estate," Feuerbach reports.

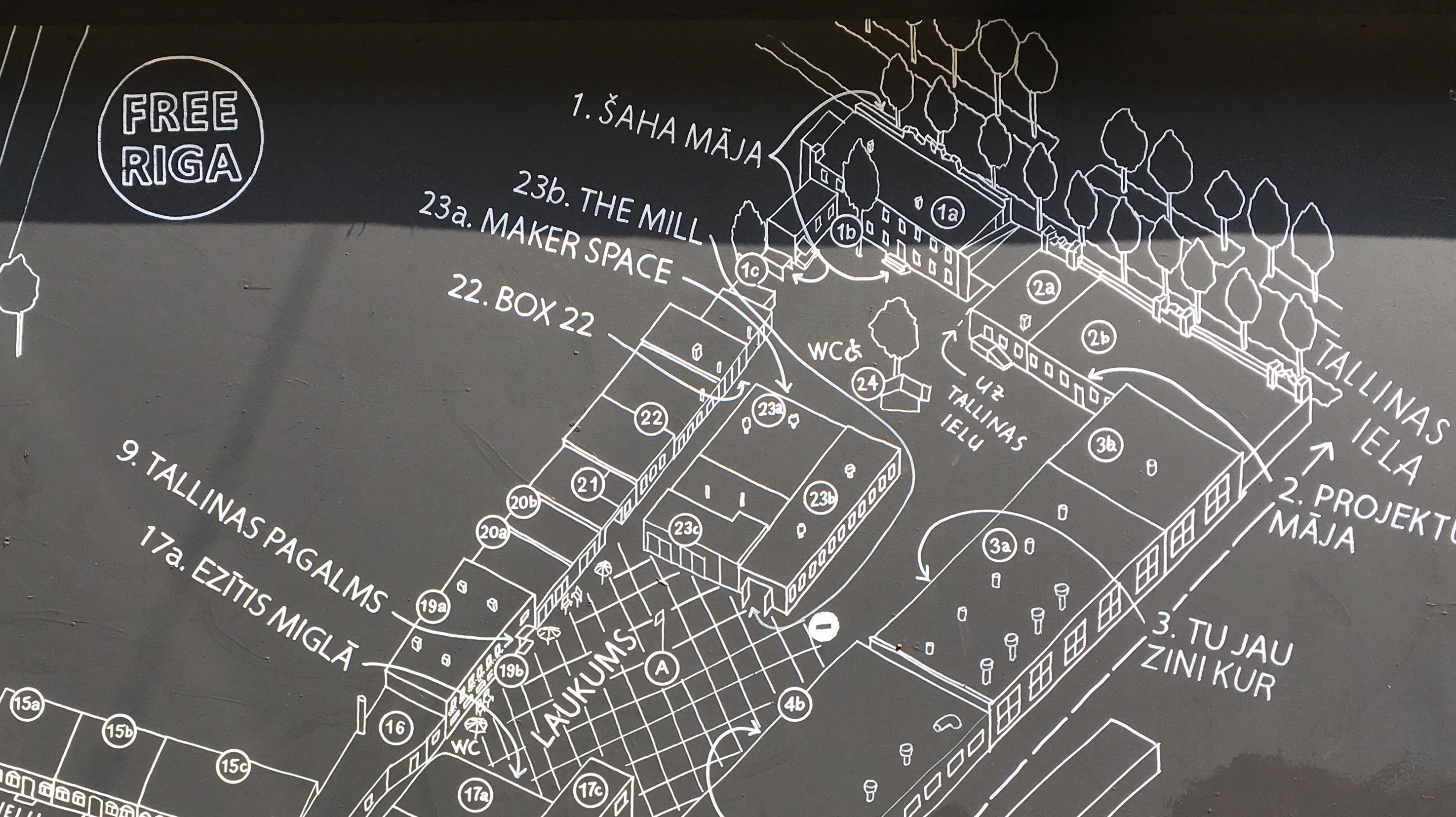

interim use in Riga under the responsibility of Free Riga, photos M. Neubert

For Grit Stillger, on the other hand, the work in the Chemnitz URBACT group was particularly important: "Here we have increased the circle of actors and thus also the circle of idea generators." In addition to various departments of the city administration and WGS, owners and owner-occupiers - small housing cooperatives, for example - were also on board. "This expands our network in which we deal with urban development," she has found. Overall, URBACT is therefore a good input, not only because it moves something in Chemnitz with European money: "Sharing our know-how also immediately leads us to reflect on our know-how in order to move forward."

Site visit during the meeting 2019 in Chemnitz: Grit Stillger (in the centre) speaks about urban development funding, photo on the right: Volker Tzschucke shows the buildings renovated by the Brühl - Pioneers, photos S. Hausmann

Submitted by sabine.hausmann on

Submitted by sabine.hausmann on