Scaling the commons: the experience of the European Commons Assembly

Edited on

21 June 2019Few these days are not obsessed by reading the news. Profound and epic changes bearing political, economic and humanitarian crisis are unfolding in front of our eyes without a sign to detour from a dangerous path. The worst news is that basic democratic principles considered as given in Western democracies are more fragile now than never before.

Commoning and the commons are concepts concerned with the management of human and natural resources. Originated in Medieval England, commons have been developed over the world assuming different names and statutes for managing rights over shared goods be land, forestry, agriculture etc.

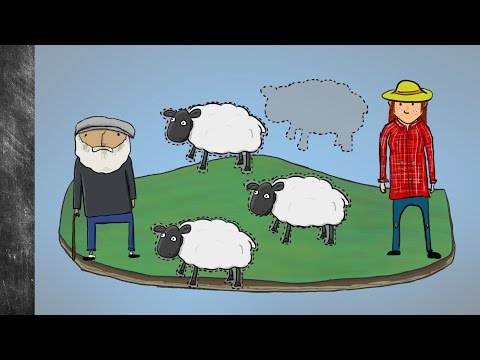

Economists, starting with the work of W.F. Lloyd in mid 19th century shaded lights on the limits of commons, further elaborated in the overly quoted classical piece as “tragedy “in the work of the ecologist G.Hardin in 1968. Hardin shows that under lack of regulations over a common good, exploitation due to self-interest of individuals, may lead to depletion of the good itself. His work has been foundational for ecology, environmental science, for studying issues related to demographic growth in relation to the notion of “carrying capacity”.

Video: Tragedy of the Commons, The Problem with Open Access

The answer to the risks presented in the “tragedy”, comes from the also well known work of Nobel prize for economics Elinor Ostrom. She demonstrates that communities around the world can indeed devise ways, such as common property protocols based on self-organisation, to govern the commons in order to assure its survival for their needs and future generations against depletion.

Thus, the concept of commons is not restricted to a certain practice, good, discipline or environment. Indeed, the “new commons” (Hess 2008) is open to encompass a variety of fields such as culture, technology, education, creativity and more generally knowledge (intellectual property, the open access, the development of associational commons, free/open source framework, etc) as shared social-ecological system (Hess & Ostrom 2007). Being so overarching, the definition of commons is also not univocally pinned-down. According to Bollier and Helfrich (Bollier & Helfrich 2014) the “commons is a paradigm that embodies its own logic and patterns of behaviour, functioning as a different kind of operating system for society”. Helfrich a well known Germany based activist, calls for commons as dynamics, requiring behavioural change of individuals and collectivities (Helfrich talk, Berlin sept 2016).

The European Assembly of the Commons

Submitted by Laura Colini on

Submitted by Laura Colini on