RiConnect themes: Planning the metropolis

Edited on

09 April 2021Rethinking mobility infrastructure offers the opportunity to have a positive impact in the metropolitan scale, through sustainable urban development.

Levels of mobility are related to the urban settlements supported (density, types of urban uses, etc.) as well as offering and costs (money, time, etc.) of transport available. Planning the territory with sustainable mobility criteria in mind and the other way around, rethinking mobility from a territory standpoint is required for having a short distance metropolis. People, activities, facilities, workplaces, leisure and gateways to public transport must be located close by, ideally under 15 minutes by foot or bicycle. This strategy fosters sustainable neighbourhoods, builds local communities, reduces social segregation and diminishes needs of mobility’s highest costs.

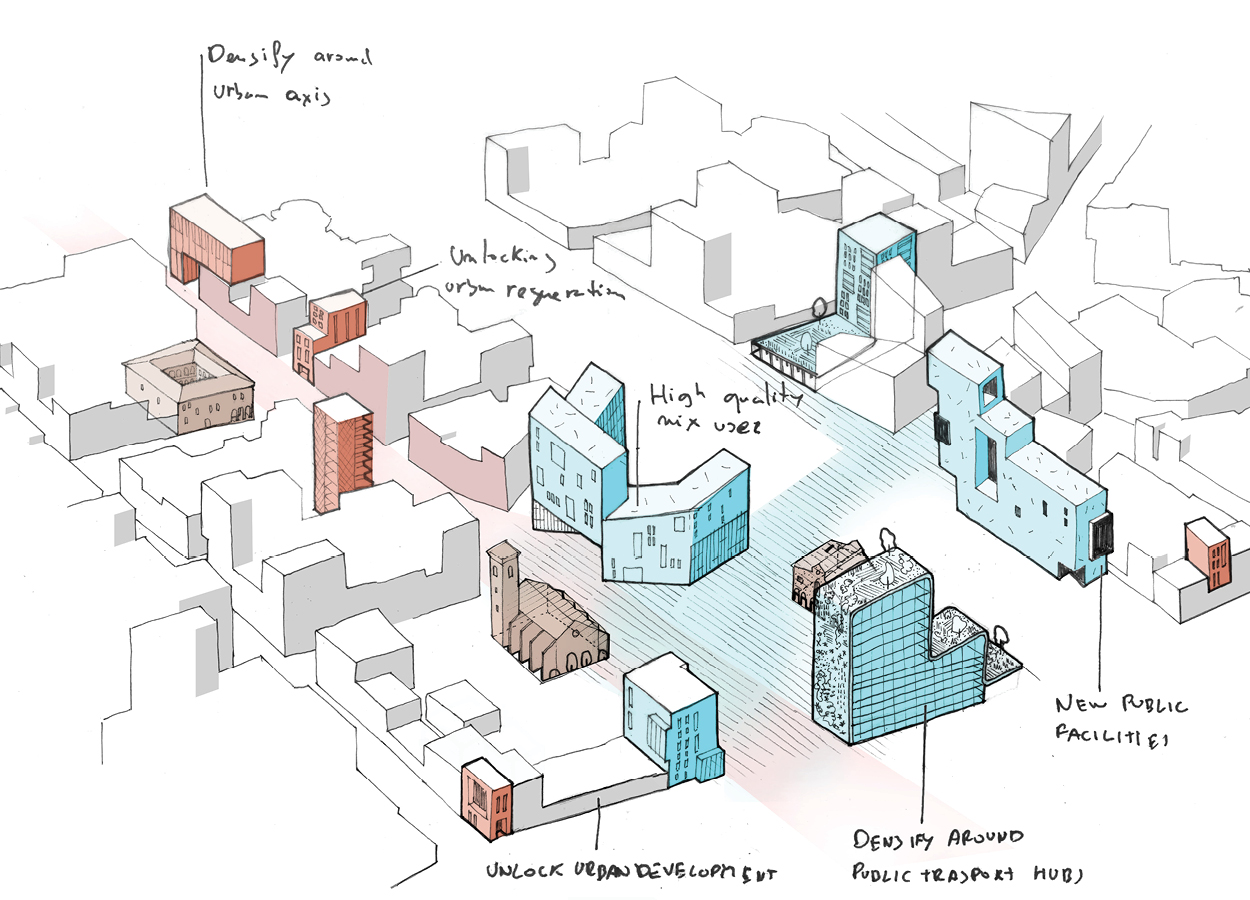

Cities began an unprecedented urban expansion when more efficient transport was invented: trains and subsequently, automobiles. New mono functional areas were built to allocate industrial estates, residential areas, public facilities and leisure and consumer complexes, all of which were physically segregated and linked by automobile only. This rapid suburbanisation process was structured with segregated car infrastructure, producing all aforementioned externalities. Rethinking this mobility infrastructure is therefore a wonderful opportunity to change the current situation, unlock opportunities for mixed uses, urban intensification and urban regeneration. The objective is a short distance metropolis, more sustainable and less dependent on cars.

TOWARDS INTENSIFYING THE MAIN PUBLIC TRANSPORT STOPS

Mobility infrastructure creates polarities. Some uses of the territory enforce centralities, and both should be considered jointly. Rethinking mobility infrastructure can create new places that are highly accessible by public transport. In order to take advantage of this privileged situation and reduce dependence on automobiles, housing, services, and workplaces should be located within walking distance, usually 400-800 meters, to the greatest extent possible. Nonetheless, levels of density, use and complexity should be planned carefully to be sensitive to surroundings and not affect local identity (Sim, 2019). Amsterdam is working on this idea. Main points have been raised by the Transit Oriented Development Institute (Transit Oriented Development Institut, n.d.), and can be summarised in:

- Walking proximity to public transport station

- Well-defined open space with active ground floor and sidewalk cafes

- Mixed use – lively, vibrant places

- Pedestrian scale with reduced and out of sight parking

TOWARDS UNLOCKING URBAN REGENERATION AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Reshaping mobility infrastructure could completely change the character of the place from an ugly place to a central and desirable place. This shift could cause a chain reaction towards neighbourhood regeneration. For example, converting what was a noisy road to a central avenue could mean a new main street for that neighbourhood with new buildings containing new cafes, shops, open spaces, housing, offices and services. This new potential urban regeneration and development might be considered in order to enhance local identity, rebalance its urban uses (mixed-use neighbourhoods), and slow the effects of gentrification.

In other cases, this could serve as a chain reaction for new urban development or major urban transformation (brownfield recovery) that may help decentralise the metropolis and reduce commuting distances. Paris and the Barcelona Metropolitan Area are working on this idea.

CASE STUDIES

La Sagrera, Barcelona / Plaça Europa, L'Hospitalet de Llobregat

After Cerdà square, Gran Via was a motorway. With the integration of the motorway, the new avenue became the front face of the neighbourhoods and activated all surrounding spaces. Today, large facilities like Barcelona’s City of Justice, Europa Square (a new economic district), Barcelona’s trade fair, houses and services are located around the avenue. Public transport was also improved to provide services for these new uses: two or three new metro stops, interchanges and bus lanes have been implemented gradually.

Rose de Cherbourg, La Défense, Paris

The traffic junction between D913 and N13 in La Défense, Paris, has been a barrier to access between La Défense and the Puteaux neighbourhood (LILA, 2014). The Rose de Cherbourg project prioritises pedestrian flow alongside the boulevard, creating new public spaces in order to become a new civic point of the neighbourhood and allocate over 100,000 m2 to offices, student dormitory lodging, commercial space and housing.

GOOD PRACTICES

- Amsterdam Zuidas, Amsterdam

- Paris Bédier - Porte d’Ivry, Paris

- Bjorvika Barcode, Oslo

- Amsterdam Central, Amsterdam

- Transit-Oriented Development Model, Montreal

- Tysons Urban Center, Tysons Corner, USA

Submitted by Stela Salinas on

Submitted by Stela Salinas on