Railway Hubs: Changing track in stakeholder engagement

Edited on

29 September 2015Railway station locations are increasingly being re-invented as vibrant, multi-functional, multi-modal urban attraction poles. This inspired the URBACT ENTER.HUB network to explore opportunities which the “Railway Hub” concept can bring to cities. This innovative transformation can also help in understanding new governance and participation models.

Redefining a vital urban resource

When the railways came to our cities in the 19th century, few obstacles were laid in their path - yet only occasionally did this life-changing transportation infrastructure penetrate the very heart of existing urban centres (Koln, Edinburgh). The establishment of terminus, or through stations, on the edge of historic centres is a more familiar pattern, taken to extremes in the array of mainline termini built to serve major cities like London and Paris. The station became monument to a new age. Responsibility for development and management rested firmly in the hands of the “railway company” in a relatively simple relationship with city authority based on land ownership transactions, provision of mutually supporting services etc. Travel was the primary factor shaping the functional role of the station. With citizenry in the role of client, customer, consumer the new urban poles provided all that was required to support this progressive transportation experience – travel information/ticketing hall/offices, waiting facilities, restaurant, cafe, newsstands, hotels, connection to cabs and in best circumstances to other transport networks.

Today these stations have mostly been swallowed up in the expansion of our urban/suburban landscapes. Over time they have adapted to accept changes in service provision (downsizing of counter facilities) and new functional opportunities, but generally remained key locations in the urban development dynamic. High Speed Train technology (underpinned by EU TEN strategy) encouraged fundamental re-assessment of the position of mainline stations – Euralille, St.Pancras, Frankfurt International Airport... and their societal role. Vocabulary changes, we talk of “Railway Hubs” which characterise a process of re-invention, adaptation and renewal.

The Railway Hub: a complex meeting of interests

The ENTER.HUB network focussed on added-value of the Rail Hub concept as an innovative force for integrated, sustainable urban and mobility planning (these two working in essential concert). Building on identity and fundaments of the past (urban, architectural icons), the station and its surroundings become a new central place in the city (paradoxically also if a hub is located on the edge or even outside the existing functional urban area). The Hub connects neighbourhoods rather than confirming railway infrastructure as a barrier (“the other side of the tracks”) and is no longer simply the domain of the traveller[1]. The offer of a network of services remains but is not limited to mobility, and can include commercial, housing, education, cultural, tourism facilities. This nodal point, urban interface repositions the station area as a “prime” location attracting new development, business and employment initiatives, and inhabitants, within a sustainable, multi-modal mobility and development logic. It is a public good where attractiveness and quality of life is reflected in the provision of public space with reduced dependency on the private vehicle - a connector, a gateway, red carpet, city lounge. (see Enter.Hub video)

While transportation is still core business of this broadened perspective, any transformation, new construction, densification or intensification of activity patterns can also generate negative impacts both in the short and long term. So when seeking to exploit the advantages of the Hub as a composite, inclusive element it is also necessary to forestall or at least mitigate potential adverse effects. In this situation affected populations (residents, shop-owners, travellers and commuters...) become privileged partners not only confined to the immediate locality but describing a much wider catchment area and broad range of interest groups. Also the Rail Hub as entity no longer corresponds to the conventional property limits of the station complex (rail company). Achieving new urban added value through integration of ancillary issues and functions - combined with smart, sustainable, inclusive growth and development ambitions - increases the complexity of the challenge facing policy makers. This requires involvement of a growing range of actors responsible for delivery of products and services (civil and network engineering, business and [private] investment, retail, [sustainable] mobility interchange management, culture, residential, public space and amenity).

While transportation is still core business of this broadened perspective, any transformation, new construction, densification or intensification of activity patterns can also generate negative impacts both in the short and long term. So when seeking to exploit the advantages of the Hub as a composite, inclusive element it is also necessary to forestall or at least mitigate potential adverse effects. In this situation affected populations (residents, shop-owners, travellers and commuters...) become privileged partners not only confined to the immediate locality but describing a much wider catchment area and broad range of interest groups. Also the Rail Hub as entity no longer corresponds to the conventional property limits of the station complex (rail company). Achieving new urban added value through integration of ancillary issues and functions - combined with smart, sustainable, inclusive growth and development ambitions - increases the complexity of the challenge facing policy makers. This requires involvement of a growing range of actors responsible for delivery of products and services (civil and network engineering, business and [private] investment, retail, [sustainable] mobility interchange management, culture, residential, public space and amenity).

Of necessity, Railway Hubs have mobilised new forms of governance, based on joint-leadership, partnership and co-production, transforming the conventional “single driver” model. This has been accompanied by blurring of traditional relationships and roles, and a general trend towards engaging with civic society, citizens and end-users. Long established competence boundaries are put in question – where for instance the public authority becomes enabler rather than provider, the railway company is freed to act as property developer and the private sector is encouraged to contribute to enhancing the public realm... The Railway Company is key, if not dominant, stakeholder - main service provider, net coordinator, infrastructure manager and often principal landowner - but cannot independently deliver the comprehensive and coherent package of initiatives required to establish the Hub formula. ENTER.HUB partner experiences shed some interesting light on how cities are concretely addressing this complexity.

URBACT cities connecting hubs to stakeholders

URBACT cities connecting hubs to stakeholders

In previewing its Hub project Creil Agglomeration highlighted the difficulty of having to work with 2 railway authorities SNCF (railway operator) and RFF (owner of the rail infrastructure) where exact division of responsibility is sometimes unclear or seems to overlap. It is however developing a core partnership to steer the process based on participation across 3 categories: land owners (railway, Agglomeration, municipalities, private property owner); transport providers (rail, regional, inter-city and local bus operators, Oise transport managing authority), and; urban planning authorities (Picardy Region, Creil Agglomeration, constituent and neighbouring municipalities). The aim is to produce a viable master plan (see diagram above) based on joint reflection around 8 working group themes (i.e. mobility, urban functions, public space...) where public consultation plays an integral role.

In Germany the city of Ulm and Deutsche Bahn (German Rail) co-piloted the project “City Station Ulm” which is embedded in statutory planning policy at all relevant levels. Together they instigated an ideas competition (2011) targeting railway station renewal, and the city initiated a stakeholder forum structure. This permanent interaction with stakeholders and local society has been instrumental in bringing new ideas into the planning process which in turn can be validated and formalised into the system of legally binding land-use plans and building permissions.

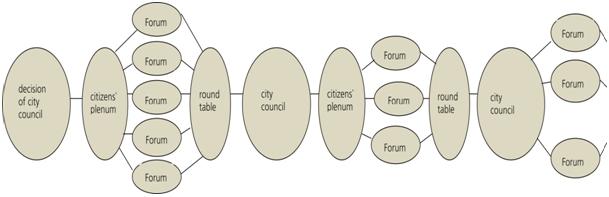

This sophisticated stakeholder participation (see diagram below) involves a cyclical round of consultation feeding input into different stages or critical moments in the decision-making trajectory. An integrated perspective is ensured by engaging groups representing specific interests, operating as focussed think tanks and channelling ideas, information (even critical feedback/objection) to the steering group. These groups are activated to follow concerns and propositions raised in a wider public consultation (citizens plenary meeting), and then to arbitrate and formulate conclusions in a targeted round table discussion on particular development options. This format can be adapted to address distinct/key issues requiring resolution through time, where it is not essential that all fora are involved in all development issues or decisions.

The city has also instigated an internet forum recognising the potential which can be achieved through new (social) media opportunities.

The extension of the “Station” into the “Hub” concept reaffirms the station, its surroundings and its multi-modal connections as a major civic asset. Conversely civic society has traditionally had very limited possibility to have a say in station development and organisation – a strategic matter, a question of technical infrastructure, a development led (finance, real estate, private or railway investment...) project. Ulm has shown that this no longer needs to be the case and the experience of Stuttgart[2] perhaps testifies that this must not be the case.

The photo on the left shows a Rail Hub linear office development, located alongside the railway tracks. Underneath the whole length and breadth of this complex is a huge bicycle storage facility (photo below). The main entrance is 50 metres from the main rail platform, on the same level and has space to accommodate 4,000 bicycles, a rental and repair facility. This implies that the Hub management structure has a fundamental

The photo on the left shows a Rail Hub linear office development, located alongside the railway tracks. Underneath the whole length and breadth of this complex is a huge bicycle storage facility (photo below). The main entrance is 50 metres from the main rail platform, on the same level and has space to accommodate 4,000 bicycles, a rental and repair facility. This implies that the Hub management structure has a fundamental  understanding of the potential and needs of this specific user group and/or that cyclists, 2-wheel commuters, students have a direct input to the decision-making and master planning process. We might imagine similar levels of facility provision in Hub developments in cities in the Netherlands (Rotterdam or Heerlen), or in Copenhagen. But are we likely to see similar responses in Italy, Spain, France, Poland or the UK, all countries strongly interested in cycling as sport, recreational activity and as transport mode?

understanding of the potential and needs of this specific user group and/or that cyclists, 2-wheel commuters, students have a direct input to the decision-making and master planning process. We might imagine similar levels of facility provision in Hub developments in cities in the Netherlands (Rotterdam or Heerlen), or in Copenhagen. But are we likely to see similar responses in Italy, Spain, France, Poland or the UK, all countries strongly interested in cycling as sport, recreational activity and as transport mode?Involving and empowering communities and end-users

As a first step to define its hub strategy, the city of Orebrö (Sweden) is attempting to assess the opinions, desires and needs of its, institutional, private and community stakeholders. The aim is to create a new linear development ranged along the rail line infrastructure fringing the centre of the city. How does the railway connect with the rest of the city (centre and suburbs), is it opportune to exploit the existing two station polarity or re-centralise around a main Hub facility? These are fundamental choices to be made by the city, its development partners and citizens. Orebrö is using media to inform and invite participation initially through presentation of a video film programmed on local television, setting out possible options and points for discussion.

A full consultation process is foreseen but initial focus is attempting to assess public opinions, using interviews at travel and shopping centres and through questionnaires circulated by social media and available in more conventional locations (schools, libraries, municipal offices). Already it has produced some unexpected results which need to be taken into account, for instance that 30% of respondents were unsure of how to make the connection between station and city-centre.

The approach of Reggio Emilia supporting the development of the Mediopadana Hub (regional - greenfield location outside the city) responds to the duality of technical/development actors in combination with wider stakeholders and civic society. A system of roundtable events functions to confront a “core group” with broader issues and aspirations raised by citizens, educational institutions, SMEs, cultural and touristic sectors etc. The URBACT Local Support Group method has helped to strengthen this dialogue. The scheme adopted can be read from a centripetal point of view (all needs, concerns, ideas are conveyed towards one or more common objectives and relevant solutions to be adopted by the core group), but also via a centrifugal perspective (decisions and projects raised through transversal exchange provide concrete answers/solutions responding to the needs and expectations of interest groups and even individual actors).

Recognising the essential added value of stakeholder input – relevant stakeholders addressing publicly relevant issues

Ultimately it is the citizenry, travellers, users of the Hub who are the beneficiaries and so the participative aspect is a key weapon in the armoury of an adapted management structure. However ENTER.HUB partners recognised that an effective leadership structure is essential in this type of large-scale complex initiative. It can be plural form of leadership or single agency driven - based on the concept of partnership but capable of taking critical decisions and putting these into operation. The Ulm (and Stuttgart) experience remind us that the final decision still rests with the appropriate elected authority while an Orebrö partner remarked “One has to be sitting in the driving seat, but plenty of others need to be in the vehicle and say where they would like to go”. Public authorities can take an exemplary lead in developing high performance co-operative working in this sense i.e. between region and city, between neighbouring municipalities, between rail and other public transport companies (bus, tram, even car-sharing), and by translating this into a wider and effective consultation framework.

Where participation is genuinely intended to inform, engage and co-produce then again according to Ulm – “it has to be incorporated from the outset and with a perspective of continuity”, but the Łódź position also has validity in that “not everyone needs to be involved everywhere” or at all times on all issues in this complex exercise. If however a participative structure is only introduced at a later stage or when difficulties arise there is real risk of obstruction, costly delay or even conflict which finally contradicts the principle of governance. In parallel, as Orebrö demonstrates how to build a strong (inter-active) communication strategy (incl. social media), Ulm suggests that the real challenge in this is to be transparent, setting out what is possible in terms of stakeholder contribution and exactly what the limits of the planning and participation process are.

The Railway Hub experience may never be fully community-led but it describes a trajectory far removed from conventional top-down intervention, traditionally defended by technical and capital considerations. ENTER.HUB partners have clearly demonstrated that the wider community should and can have a highly significant role to play in developing this civic asset.

Photo references:

1. Łódź (Poland) – The Board of the New Centre of Lodz. Construction of Fabryczna Station

2. Creil Agglomeration (France) – Anticipating HST

3. The Ulm Stakeholder Forum (Germany)

[1] Estimates suggest that more than 20% of people using modern station complexes are not travellers

[2] Intense citizen protest against the Stuttgart 21 mega station project (50,000 people on the street in September 2010) forced a referendum in the Landtag Baden-Wurttemburg in 2011 – critical consequences at national level, in political terms and major impact on budget and timing.

Submitted by Philip Stein on

Submitted by Philip Stein on