Planning Safer Cities, design, implementation and evaluation – Guidelines

Edited on

20 February 2023Planning Safer Cities, design, implementation and evaluation – Guidelines

This document was produced by the UrbSecurity Network, an URBACT Action-Planning Network focused on urban security from May 2020 to August 2022.

Table of contents

0. Executive Summary / General Guidelines

1. Challenges tackled

2. Lessons Learnt

3. Tools and Methods

4. UrbSecurity Case studies

a. Leiria - Urban Planning Serious Game

b. Michalovce - Surveying citizens

c. Faentina - Regional Governance model for urban security

d. Mechelen – Reducing nuisance in city parks

e. Szabolcs - Rethinking lightening of public areas

f. Madrid - Safety and security in open public spaces

g. Longford - Using street art to revitalize the city and increase perception

h. Parma - Restoring security perception in city parks

i. Pella – Safe mobility

5. Conclusions

0. Executive Summary / General Guidelines

UrbSecurity is a project under the URBACT Programme, led by the Municipality of Leiria (Portugal), and joined by 8 other European cities. The project focuses on co-creating an integrated approach towards urban safety and security, based on transnational change of experiences, knowledge sharing, and common methodology development activities, as well as on cooperation of URBACT Local Groups and implementation of a Small-scale Actions as pilot activities in the partner cities, which faces various challenges in connection with urban safety and security.

Urban safety and security are becoming a key element in all public policies as a driver for sustainable development. The United Nations' New Urban Agenda introduces urban safety and security as one of the driving forces of any urban policy that seeks to respond to the multiple challenges of today's cities. Citizens often experience both a real and perceived lack of urban safety; within urban centres, people do not feel safe walking the streets, particularly after dark, which results in little activity in the evening or at night that affects economic activity in the city centre. Thus, cities have several challenges to address.

Safety is currently considered as one of the aspects affecting the quality of life in the EU. The framework developed by Eurostat proposes several methods of measuring safety, and in particular, an analysis on various parameters that determine safety and the relative perception of safety of an individual of his or her living environment, both personal and urban, has also emerged.

Building on the UrbSecurity project transnational meetings cycle outcomes, this thematic report captures and highlights the main contributions, learning points and guidelines.This intends to be an orientation paper including guidelines to help cities facing their challenges and changes, based on specific UrbSecurity project partner cities experiences and evidence-based recommendations.

1. Challenges tackled

We are living through complex times. As cities are growing in an accelerated world with unprecedented population mobility, conflicts naturally emerge. In this context of globalization, cities are the main stages of interaction.

The same spaces are used by different people. People of different ethical and cultural backgrounds coexist. In cities, multiculturalism is experienced, but also the effects of differentiated development. Richness exists side by side with poverty.

Paradoxically, in the era of instant communication, interaction channels are lacking. Gentrification processes generate human movements and transformations that affect neighbourhoods. Roots are lost and the sense of community does not always develop. Isolated islands of luxury and poverty remain, separated by no man's spaces.

The physical and cultural spaces of social construction that could leverage social empathy are missing. Public space plays a key role as a place of aggregation and dissipation of conflicts, but only if city management tends towards greater participation of the population in decision-making processes.

The creation of collective identity and a sense of ownership comes about through the involvement of populations in a city that considers them, made for them. Planners, urban planners and political decision-makers try to make their proposals and achievements, but they need to consider who lives in the city.

UrbSecurity has successfully operated, designed and demonstrated a set of actions and integrated plans, facing these identified challenges.

2. Lessons Learnt

Capitalising on project partner cities’ lessons learnt, this document aims to guide each city into a specific solution for a well-identified urban area.

Various are the lessons learnt by the UrbSecurity partners, deriving from an evidence-based approach taken in the project, where each lesson, each indication and each recommendation derives directly from observations and results validated in real-life demonstration, testing and analysis conducted within the project.

Lessons that could be capitalised and should be followed when addressing affordable measures facing security at urban level.

Lessons learnt, concerning major areas addressed within UrbSecurity, include:

● Focus on awareness-raising activities for citizen engagement in urban safety and security

The level of involvement of awareness of local inhabitants into their active potential role in improving urban safety and security is often relatively low (e.g. see the Rethinking lightening of public areas case study in Szabolcs). It is essential to mobilize social capital among the citizens (e.g. through nudging tools to “pass the message”, activities neighbourhood watch, intergenerational programmes, sport, cultural and other community development events, awareness raising and increasing tolerance and understanding, mentoring, presentation of success stories), in order to facilitate a higher level of citizen participation, achieving prevention of becoming of a perpetrator or a victim, minimising tension within the communities, building trust, making people feel that their voices matter and enhancing the sense of sensibility and responsibility.

Key activities include identifying local opinion leaders, creating conditions for communities to participate in the planning and implementation, facilitating capacity-building initiatives for communities to participate meaningfully, regularly communicating with the local community and organising awareness-raising events among different target groups.

● Target particularly young people and schools

Working on specific communication channels addressed to young people and schools is key for success of urbans security programmes (e.g. see the Faentina Regional Governance model case study). The role of schools is in fact essential in reaching not only students, but also families: students can easily disseminate information once they go back home. This is particularly important when it comes to foreign families, as their children might facilitate the communication with families and parents who might have some problems in speaking the local language.

● Reach critical mass of participants and representatives

As evidenced in several UrbSecurity measures (e.g. see the serious gaming case study in Leiria), in order to reach an effective impact it is necessary to ensure that a relevant number of citizens and users, of proper diversity and representativeness of the various social groups, other than representatives from the local institutions and population, are involved in the applied measures. It is also relevant to attempt to replicate the identified processes in several urban areas, granting broad recognition and trust. Here, in this field, “small is not good”.

● Promote an integrated approach

Integration has various facets. In order to connect innovative solutions and avoid creating new problems, it is crucial to adopt an integrated approach which considers and combines a number of different dimensions, “hard” and “soft” investments (e.g. see the Parma - Restoring security perception in city parks). An integrated perspective also means working for developing new policies built on: vertical cooperation between all levels of government and local policy makers, horizontal cooperation among policy areas and departments of the municipality, and “territorial” cooperation between nearby cities or aggregations of city.

● Provide a combined socio-economic impact assessment

In order to avoid competing priorities, as political priorities influence how resources are shared and can change in time and some projects could gain more attention than others from the different departments, a social and economic impact assessment should be provided, in supporting initiatives aimed at increasing urban security (e.g. see the February 2022 e-University Workshop report). This implies the involvement of a broad range of stakeholders, monitoring implementation against economic, social and environmental objective, quantified, measurable and ambitious KPIs.

● Ensure timely implementation in practice of outcomes

It’s important to always manage to implement in practice outcomes deriving from surveys / games / analyses, in order to sustain the potential relevance of citizens involvement, facilitating and incentivising a large participation (e.g. see each and every UrbSecurity case study). Moreover, delays in the implementation of actions can demotivate citizens. Delays in the process of public procurement or of the works not foreseen can temper the initial positive impact in the city. A timely implementation is key and should be ensured.

● Promote institutional cooperation

Institutional inter-cooperation should be always sought, e.g. between the mayor, as a government official, and local or state police forces (e.g. see the Parma - Restoring security perception in city parks), merging and benefiting from mutual specific functions attributed, with respect to which they may use local tools and systems (e.g. video-surveillance systems) to protect urban security, for the control of the territory and for the prevention and rationalization of actions against criminal and administrative offenses as part of the measures to promote and implement the urban security system for the welfare of the local community.

● Monitor and anticipate the legal framework

It’s important that changes in rules and legislation both at national and at EU level (e.g. GDPR in connection with CCTV system) are monitored and followed (e.g. see the February 2022 e-University Workshop report). For example, all actions related to any form of surveillance, as a CCTV system, must comply with the local legal framework but each country has currently different rules. Sometimes there are also specific ethic concerns to attend. Not only the viability of possible actions should be checked against the current legal framework, but even possible changes in the legislation should be anticipated (e.g. resulting from EU harmonisation).

● Follow the UA “security by design” principle

The CPTED ISO 22341 provides a standard framework to implement the “security by design” principles in the everyday planning of the city, creating a layer of security in every public intervention in the public space, although they often conflict with current rules and local/national regulations. As clearly outlined within the February 2022 e-University Workshop, this can be effectively overcome checking and applying the Urban Agenda for the EU Partnership on Security in Public Spaces “10 Rules of Thumb for Security by Design”.

● Build a suitable funding strategy

As evidenced within the February 2022 e-University Workshop, many cities usually rely on municipal or local funds to finance their security related actions. Building a funding strategy with mix funding that looks for other opportunities of funding represents a good practice, to support the feasibility and operational deployment of the identified measures. Important will be also to train internal municipal staff, so that they can identify in a more informed manner funding sources and supervise in an effective manner also eventual external support from specialised teams. However, Funding Mismatch should be avoided (making sure projects are not developed based just on the local available funding, but on the actual needs of the city, avoiding biasing the type of interventions).

● Aim at achieving the pride of place perception

Increasing pride of place and an enhanced sense of identity and people ownership can be considered the final overall aim, to promote passive self-policing of the town centre, making it socially unacceptable to behave in an anti-social way, damaging the reputation of the town, while making others feel safer and more secure (e.g. see the Longford - Using street art to revitalize the city and increase perception). This should be accompanied by a co-ordinated action dealing with increased perception of the city, with positive reporting on activities that build community spirit and outline positive events, interventions and initiatives and how these contribute to a sense of community and pride of place, improving the overall sense of security.

3. Tools and Methods

There’s no solution that ‘fits-all’, requiring instead a holistic approach to problem solving, through a portfolio of tools and methods, that were designed and tested within the UrbSecurity project, embracing a reach and variegate set of approaches:

▪ Urban planning

Urban planning is a key tool to create a liveable milieu for citizens, thus creative placemaking and urban safety go hand in hand. Urban design contributes to safer public spaces in many ways: better visibility of places ensures natural surveillance and safe routes for pedestrians; people use more frequently an attractive, aesthetic, and properly maintained place as a welcoming and inclusive community space, and, in consequence, human presence can keep criminals away. Traffic signs and traffic calming measures have to be clear and unambiguous, compliance with the rules and community standards have to be regularly monitored.

As witnessed by the Szabolcs UrbSecurity case study, particularly through the optimal location of the streetlamps, this tool contributed significantly to the attractiveness and liveability of the city. Design principles have were duly considered, that increased also the subjective sense of security among users of the urban space.

▪ Usership and citizens surveying

Usership and citizens surveys (see the Parma UrbSecurity case study) are able to address effectively community needs, resolve factors of insecurity, identify conflicts among groups of park users, and manage urban assets more effectively: all keys to maximizing the security, the safety conditions and liveability of the urban area. The survey can be used also to collect proposals for improvements from citizens and users and to identify areas and places on which focus ongoing feasibility studies and future improvement plans.

Cities have in fact access to specific data about crimes or traffic accidents, but often limited information about the citizens' subjective sense of security. Surveys can even use mobile smartphones and online access to receive feedback, making this task of “listening to citizens” easier to implement, store and analyse (see the UrbSecurity digital tool called “Safe Michalovce” - https://michalovce.web-gis.sk/ - aimed at creating an “Emotional map of the inhabitants of the city“).

▪ Multi-level communication

An efficient communication plan, which involves several sections of the local community, is not only important to reassure citizens, but to exchange good practices that could be implemented in other urban contexts, according to the local possibilities and challenges (see the Faentina Regional Governance model). The language used needs to take into consideration that the general population do not always possess a good understanding of technical issues. Communication needs to be characterized by clear statements and key actions. The communication policy must underline the positive actions that the local administration has been implementing in the field of urban security: this strategy will increase confidence in the local authority. It is necessary to access to those communication channels that are also used by the local stakeholders: schools, shops, industry, citizens themselves and the local police.

▪ Serious Gaming

One of the most promising solutions to meet the needs of all stakeholders in a participatory urban planning process are games. It is possible to learn with game dynamics to build more interactive, effective and enjoyable user experiencing through the application of gamification, serious gaming techniques and analogue games, popularly known as board games. These are games of modern design, taking advantage of the mechanisms and differentiated experiences they provide to users. This type of games has the advantage of being easier to develop and adapt. They have lower entry barriers than digital games and rely on player facilitation and support techniques that would be worked on by the municipality's technicians. They are also easier to adapt and configure, encouraging collaboration between participants by requiring direct activation by the participants, with no hidden information.

As witnessed by the Leiria UrbSecurity case study, these techniques can be successfully used, in existing processes or generate new types of approaches, bringing tangible and valuable impacts.

▪ Neighbourhood watching

Groups of neighbourhood watch demonstrated their effectiveness (see for example the Parma UrbSecurity case study) to identify situations at risk and create a stronger network of vigilance among citizens. It's a simple but effective way to involve citizenship in participatory safety paths. So, residents control their area and report to the municipality if there are problems.

▪ Video surveillance

A network of video surveillance in the hot spots of the city, monitored in collaboration between urban government and municipal police, resulted to be particularly effective (see the Madrid UrbSecurity case study). The regulatory framework on security in fact often attributes to mayors the task of supervising public order and safety. The mayor, as a government official, contributes to ensuring the cooperation of the local police force with the state police force, within the framework of the coordination directives issued at national level. In the context, employing video surveillance systems as tools of primary importance for the control of the territory and for the prevention and rationalization of actions against criminal and administrative offenses resulted to be a major part of the measures to promote and implement the urban security system for the welfare of the local community.

▪ Street-art performing

Street-art allows making small-scale, high-impact interventions in the streetscape to improve the appearance and perception of the town to reduce the impact of vacant and/or derelict properties (see the Longford UrbSecurity case study). Activities can include sponsored and private initiatives to paint and repair properties in high profile and blackspot locations, improvements in public and private lighting solutions, incentivising shopfront improvement, to highlight positive features to encourage active and passive security. An attractive environment increases activity and passive security, particularly in targeted areas.

▪ Nudging

Together with spatial design, nudging techniques and tools can be very effective to change unsafe or unsecure behaviour in urban environments, in particular due to its potential impacts on dimensions like Risk Perception and Behavioural Change. Contrary to crime prevention, where compliance tools are used, such as education, legislation or enforcement, a nuisance situation does not imply the existence of crime, so the intervention of police forces is rarely the best solution to deal with it. By influencing the behaviour of citizens in a positive way, cities can much better tackle the problem (e.g. see the Mechelen case study).

4. UrbSecurity Case studies

a. Leiria (Portugal) - Urban Planning Serious Game

Civic participation is essential for sustainable urban development, but few tools and solutions are available to foster it in practice. One of the new approaches that's being tested is the use of serious goal-oriented dynamic games. UrbSecurity has implemented one of these approaches with surprising results.

The effort to make the planning and management processes of cities more participative, avoiding hierarchical top-down processes, is not new. But it has been difficult to achieve processes in which the populations participate actively on a large scale, even in matters of greater proximity. Sometimes it has even been difficult to include representatives, experts and technicians (stakeholders) in the elaboration of a more participatory urbanism.

Planning processes tend to be long and complex. Citizens feel that their opinions are not turned into actions. There is a lack of communication and evidence that civic and public participation is worthwhile, that it pays off for the time citizens have invested in these activities. It is not clear to citizens that participation pays off. Many participatory processes tend to be participated in by the same citizens each time, bending the needs and priorities of the inhabited territories. It is easy to unleash hate battles, of one against the other, making the necessary collaboration to live in shared spaces impossible. There is a lack of efficiency, collaboration and the transformation of these processes into something pleasant and consistent for citizens. Even technical and planning experts find it difficult to make a difference, due to lack of means and knowledge to implement new methods. On the other hand, political decision-makers may be wary of the supposed loss of power, but mainly of the waste of time and slowness of extending decision-making to the people. Ultimately, everyone wants achievements that improve the city.

The approach to tackle such challenges, demonstrated within the UrbSecurity project in Leiria, focused on serious games.

UrbSecurity implemented a collaborative process in which multiple stakeholders worked with analogue games to discuss, identify problems and find joint solutions to improve urban security in the city of Leiria, focusing on two distinct urban areas. The focus was the historical city Centre. of Leiria and on a more recent expansion area, characterized by a high multiculturalism. For each area, the Municipality of Leiria identified several stakeholders as collaboration partners. A work plan was defined, consisting of three distinct steps for the implementation of an end game as a collaborative planning tool.

The process was created specifically for the two urban realities in question, conducted by researchers at the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of Coimbra and at the city Centre for Territory, Transport and Environment Research. The researchers acted as trainers of the municipality technicians, preparing them for the game’s facilitation process, but also as designers of the games adaptation and development. The development of the various stages of the games to be used in UrbSecurity were also built following the principles of co-creation between the researchers and the municipality technicians. Thus, the very conception of the method leveraged the spirit of empathy and collaboration among the technical team. Although the objective was to generate a game that would be a planning tool, many games were used during all stages of the process. This allowed unique participatory dynamics to be generated, as they were games that helped to build another game that resulted from the interactions and participation of stakeholders and technicians.

In the first stage, participants interacted through game dynamics that took place at various work tables, each accompanied by a technician from the municipality. Some modern storytelling and creativity-enhancing board games were used to collaboratively identify problems and solutions leading to increased safety in the urban area in question. After this, the participants were invited to vote on which would be the main problems, followed by a group work process to fill in preliminary proposal sheets for the main problems found. These proposals were then put to the vote again. One session was held for each urban area, lasting around 3 hours and with over two dozen participants in each session. The sessions identified as solutions increased police surveillance, public lighting, improved public spaces and transport, urban regeneration and social programmes.

At the second stage, already more conditioned by the effects of the pandemic, it was necessary to reduce the groups and work with a maximum of six participants per session. Four such sessions were held, two for each study area. In this second session, the participants continued to identify problems and solutions, interacting with the cartography of the various zones. Drawing games were adapted in order to generate new communication and expression dynamics among the participants.

Graphic representations were made on maps of the urban areas, generating a new tangible aspect of information collecting. It was also a strategy to foster empathy among participants. Priorities were collected in this phase, resulting from the two graphic expression games. This was followed by a voting process that determined the priorities of each working group. As in the first stage, stickers with multiple votes were distributed to the participants, which generated a hierarchy of priorities, as votes could be freely assigned. This graphically impactful, transparent and interactive way of voting helped to reinforce empathy among the participants, making it clear what each one's concerns were. Although there were some opposing priorities, no conflict was felt among the participants. The second phase was preceded by the exposure of additional technical information to the participants, to support decision-making. Data was presented and videos of the zones were shown. The pandemic context prevented however the sites from being visited in person.

The second phase was complemented with online sessions which the facilitator simulated some of the design games through online collaborative tools supported by video streaming platforms. Despite the limitations, the online process also generated debate, problem identification and some prioritization. It was a way to make up for the constraints that prevented the level of interaction that was experienced in the first session.

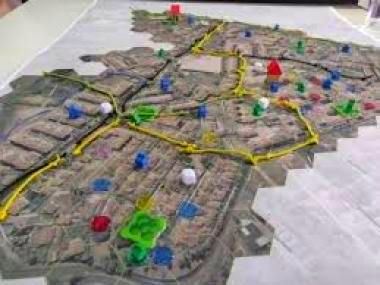

The third stage resulted from the culmination of the two previous stages. It was the data previously collected with the problems, priorities and proposals that allowed building the game that would then be the desired collaborative planning tool. The proposals were counted and a game economy was generated that launched a collaborative challenge to the participants. Modern board game mechanisms were conjugated to support the narrative, making it easier to read the increasing complexity of the proposed solutions. Participants had to take on the role of a mayor and manage, over 4 years, the budget to improve urban safety in the area concerned. To do this they would have to make individual and collective decisions. In order to implement large-scale solutions, they would have to discuss and combine their respective budgets. Each player received a small fraction of the budget per year (per game round). This represented their voting power. Implementing buildings for social projects, extensive public transport networks and large public spaces required the cooperation of several players. The available options were represented by analogue game components, cubes, discs and coloured wires with appropriate captions. The game took place on the map of each urban area, divided by a hexagonal grid that helped to frame the effect of distances and areas of influence of the proposals, such as the area of coverage of policing, video surveillance, the length of a bicycle path or where to focus on territorial marketing.

The third stage also suffered from the restrictive effects of the pandemic. Four sessions were held with six participants at a time, two for each urban area. The same strategy was adopted as in the second stage. Four proposals emerged, two per zone. It was concluded that, despite some similarities, the proposals were different, very dependent on the participants and the dynamics that were generated between them. This lead to conclude that the participation processes should be broadened to include as many participants as possible, ensuring that there is diversity and representativeness of the various social groups. It was proven that games generate solutions and are collaborative tools to express the will of the participants. It also became clear that the process how the playable approaches are created is of utmost importance, as is the method of data collection and processing. A playful environment is generated that reinforces empathy and collaboration, but without losing focus on the seriousness of the issues at stake.

The game development process resulted from the dynamics implemented in the previous stages, also fed by social games. This method was only possible because it was developed with flexibility and adaptability by the technical team. A stricter format could hardly have had the same results and been implemented quickly and at low cost. From the data collection it was found that the participants were surprised by the dynamics implemented, having admitted that they were initially suspicious because it was a process fed by games. But when they saw the results they regarded the process as a positive one, something that should be continued, and that it would be disappointing if the proposals developed were not implemented in practice.

In the future the final game should be tested with more users, and preferably with more representatives from the local population. It will also be relevant to attempt to replicate this process in other urban areas, since the model followed can be applied to any urban territory and to other issues besides urban security.

b. Michalovce (Slovakia) - Surveying citizens

In order to respond to the challenges of the town citizens and improve the quality of their lives, it is necessary to enhance the participation and communication with the residents, enabling them to express their feelings about the safety and security in public areas.

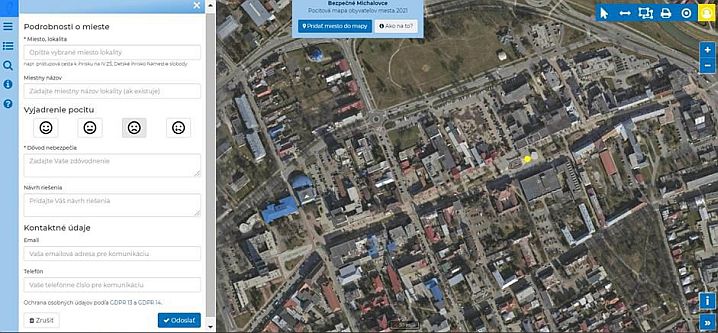

For the scope, the Opinion map was launched and created in Michalovce as a new layer of feelings within the town Geographic Information System.

The need to increase the quality and safety of the public areas is obvious in many Slovak cities, Michalovce included. Thanks to the UrbSecurity project an opportunity to enhance this condition emerged, as well as communication with the citizens in the town, who presented their comments in the Opinion map to identify the place reflecting the signs of danger and with their participatory approach to propose their own solutions.

In connection with the professional community a Manual for creating safe public areas was created, to be a conceptual material which supports the uniform approach in solving the same problems in the town, raising safety and, last but not the least, beauty of the town.

Within the territory of the town of Michalovce criminality is being monitored by the State and Municipal police in the field of violent, moral, property and economic crimes. The order and security is kept by the Municipal police on their regular patrols focusing on the areas with the most frequent lawbreaking.

Criminality in the district of Michalovce has the decreasing tendency from the long-term perspective. Since 2014 the State Police have been reporting the decrease in criminality whereas the percentage of the created up crime rate has been increasing. The reasons for such a condition were regular patrols, fining threats, higher law awareness of the citizens, CCTV surveillance 24/7 as well as crime prevention in schools.

Main challenges/problems found in the city/ region (factors of insecurity) include:

▪ the town doesn´t have fully revitalized public spaces for pedestrians, cyclists, road users,

▪ public spaces are not completely barrier-free and accessible for people with visual impairments. The town is gradually revitalizing due to the lack of finances;

▪ there is no general transport;

▪ there is no unified manual for creating public spaces;

▪ there is a segregated Roma community with an inadaptable behaviour, the existence of delinquents of anti-social activity and illegal conduct in the community. In a segregated site, inhalant abuse by adolescents occurs;

▪ the majority of the population has a predominantly negative attitude to the minority of the Roma due to the behaviour of the minority.

The Opinion map aimed at identifying unsafe areas in the town, using a map where citizens were expressing their feelings about the place they know.

The aim of using this tool was to make the residents actively participating in the project as the town authorities have poor connectivity with people and address their needs concerning security in the town.

Included activities started with citizens of Michalovce choosing a place on the map, expressing the feelings in their description of areas and suggesting the solutions to the unsafe areas.

This was accompanied by direct marketing through social networks for the communication with citizens, addressing the residents of the town through sending SMS messages and organising commercial campaigns.

The overall scope was to target the following dimensions of urban security:

▪ Prevention – after identifying the unsafe places in the town by the residents and experts within the project tool of the Opinion map and Manual for creating the safe public spaces, the planned revitalisation of such places should meet the prevention requirements;

▪ Perception – with the participatory approach in the SSA (Small Scale Action) Opinion map there has been the high intention to increase the citizens´ perception of the security;

▪ Social cohesion – as the one of the key issues of the urban development policy is to improve the well-being of the citizens from all backgrounds and social statuses regarding solidarity in the society which can be ensured by the sustainable economic growth mainly. It helps to break down the barriers among members of the society avoiding the social exclusion;

▪ Governance – The Opinion map is a great tool helping town authorities work better with communities in sense of improving community participation to co-create safe public spaces. The Urbact Local group includes the stakeholders seen as collaborators in governing processes stressing public-community governance.

The results coming out of the SSA Opinion map were introductory data for architects, experts and professionals in the safe areas to work on the revitalization of the town with the unified approach to the problem solving.

Open issues left after the deployment of the Opinion map included:

▪ an overall limited participation of residents (more comments should have been expressed);

▪ low interest of residents in the local public affairs;

▪ Covid restrictions did not allow for face-to-face meetings;

▪ insufficient interest of the stakeholders: Municipal department, Fire department, representatives of citizens;

▪ time challenge to respect the project schedule.

c. Unione della Romagna Faentina (Italy) - Regional Governance model for urban security

Urban security policies built upon integrated and participated approaches have shown how repressive responses to crime – or anti-social behaviours – represent a limited strategy that cannot be the winning strategy in the long term. Therefore, it is fundamental to start working to achieve coordination and governance in the field of urban security.

Different institutional levels (central State, Regions, local administrations) need to be able to act by implementing different forms of vertical subsidiarity, in line with their own competencies. Coordination particularly refers to horizontal subsidiarity, meaning how the local stakeholders can contribute to urban activities: urban security policies benefit from the support of several actors, e.g. association groups, voluntary groups, neighbourhood watch groups, schools, etc.

Key actions include:

▪ formalizing a table for discussion with the local stakeholders in the field of urban security;

▪ fostering the development of an integrated culture for urban security issues, by engaging the local stakeholders and community in capacity building activities. This approach allows to identify knowledge gaps in the field of urban security and, therefore, it enables the local authority to work on sharing information, by engaging the permanent Table on security;

▪ developing a specific communication strategy, leveraging the power of social media. Exchange of information and experiences on local criticisms contribute to identify priorities on the basis of real and concrete issues.

▪ implementing memoranda of understanding with the institutional levels in order to formalize collaborations and synergies between those actors that are particularly involved in the field of security. These agreements would enable joint preventive and repressive actions between the local and national police, and the local administration;

▪ investigating activities, data reading, training, and organization of events to promote legality, realized in the framework of the monitoring centre for legality.

The participation of the local stakeholders and the implementation of the activities imply however a difficulty in keeping commitment levels high. The participation is indeed fundamental in order to guarantee a first grade of engagement from the associations, that could be further widened to the rest of the local community.

A multilevel governance model should always characterized the urban security strategy, formalizing an integrated and participated approach.

The institutionalization of a permanent worktable can guarantee dialogue with the realities of the territory in the field of urban security.

Urban security is in fact not an autonomous concept: Urbact Local Groups should gather together those actors who are actively involved in the field of urban security and who can provide contributes towards more effective urban policies.

The local police is often a privileged interlocutor: nevertheless, essential is the commitment to engage through a cross-cutting approach other sectors of the administration, namely community services, public works, urban planning, institutional communication, education.

Communication, in particular, is an essential element when sharing and building security policies. Urban security policies must be in fact joined by an efficient communication plan which involves several sections of the local community.

Not only it is important to reassure citizens, but to exchange good practices that could be implemented in other urban contexts, according to the local possibilities and challenges. Besides, the language used needs to take into consideration that the general population (and professionals’ sectors as well) do not always possess a good understanding of technical issues.

Communication needs to be characterized by clear statements and key actions. The communication policy must underline the positive actions that the local administration has been implementing in the field of urban security: this strategy will increase confidence in the local authority.

In order to elaborate an efficient communication policy, it is necessary to access to those communication channels that are also used by the local stakeholders: schools, shops, industry, citizens themselves and the local police represent “channels” to disseminate information.

Key actions include:

▪ elaborating information campaigns with the support of online tools, theatre performances and flyers;

▪ organizing conferences and seminars, by engaging universities and schools;

▪ strengthening the dialogue with schools;

▪ working on specific communication channels addressed to young people;

▪ training citizens and operators (local police staff and city sectors particularly involved in the urban security issues).

Furthermore, digital illiteracy should not be underestimated: the elderly, but also other sections of the population, might have some difficulty in accessing social channels and online platforms. It appeared therefore that alternative ways to reach these people need to be explored, such as offline channels of communication.

The role of the schools is essential in reaching not only students, but also families: students can easily disseminate information once they go back home. This is particularly important when it comes to foreign families, as their children might facilitate the communication with families and parents who might have some problems in speaking the language.

Similarly, shops and trade operators can engage in dissemination activities.

d. Mechelen (Belgium) – Reducing nuisance in city parks

Every day, Mechelen’s city guards need to manually open and close 18 public parks. On top of that they perform regular visits to parks where complaints regularly come from. The city council plans to create about 10 additional parks. Often, nuisance is encountered in city parks.

Nuisance, meant as annoying, unpleasant, or obnoxious behaviour, is a topic having a wide range of possible angles: the design of a park, the type and location of its furniture, how to influence behaviour, etc.

With the collaboration of a comprehensive set of stakeholders (Police, Youth organisations, Department of youth, Department of park maintenance, Department of prevention and safety, Regional cleaning initiative and Flanders government), nudging approaches were considered (intended as attempt to alter people’s behaviour in a predictable way), other than viability tests (namely process/methods to be implemented when (re)organising a public place).

Local surveys and interviews evidenced that girls prefer to play and to chill while looking for a safe space. “Guys need to change their behaviour. Girls have the same rights, but the guys think they’re tuff” is an often-heard comment. They have complaints about safety, lack of activity, drug abuse closing hours. Girls would like parks with more integration of type of activities for different groups of age. They’d like to be involved in the process of rearranging a park.

Reducing nuisance can (partially) by achieved by rearranging an area (parks & squares, residential areas, and development projects). Along with local groups, habitants, city departments, police and other involved, the idea is to come up with a guideline, listing elements to considered and passed on to architects and implementing departments, vs elements to be avoided.

Elements to be considered include:

▪ attracting different categories of age. This enhances natural supervision;

▪ providing see-trough fences;

▪ reducing the number entrees and exits;

▪ adapting the kind of shrubs to the location like thorny one nearby window;

▪ making the location of the benches out of the sun but with an overview;

▪ providing activities for boys as well as for girls;

▪ using gamification towards the bins;

▪ providing fibre-connection for monitoring equipment;

▪ implementing active frontages (shop, pub, restaurant).

Elements to avoid include:

▪ spreading areas depending on their function;

▪ hard fences;

▪ removing weeds;

▪ removing broken elements (plays, city furniture, lightning);

▪ removing shelters;

▪ bins on hidden locations.

The whole is based on the CPTED (crime prevention through environmental design) idea, having 4 guidelines:

▪ Accessibility and control of it

▪ Natural supervision and social control

▪ Functions and managing the decline

▪ Technological support

One of the items of reducing nuisance in public parks is to give people ownership. Linked to that, comes the idea to provide them something for which visitors not only see the use but are so keen to have it that they’ll take care of it.

Combined that with the idea of gathering data we came up with the suggestion of a sustainable smart bench. Basic solar-powered smart benches allow visitors to charge their phones and tablets. USB ports and wireless charging points are provided.

Depending the options, it could be added a Wi-Fi connection and sensors allowing to return data on the charging volume (the use of the bench), air pollution, etc.

Benches were installed in 2018 and over those years there were no signs of vandalism, indicating people appreciate the idea and are taking care of it.

Pro’s

▪ fairly flexible as the benches can be moved from one place to another

▪ sustainable due to solar powering

▪ useful as the benches attract a lot of people

Con’s

▪ Pricey

▪ Becomes hot in the summer

e. Szabolcs 05 Regional Development Association of Municipalities, SZRDA (Hungary) - Rethinking lightening of public areas

SZRDA is an association of 44 municipalities in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county, in north-eastern part of Hungary representing all settlements in this area. The centre of the region is the City of Mátészalka known as “City of Light”.

Mátészalka has a population of 15,874 people with approx. 20-30% of Roma people.

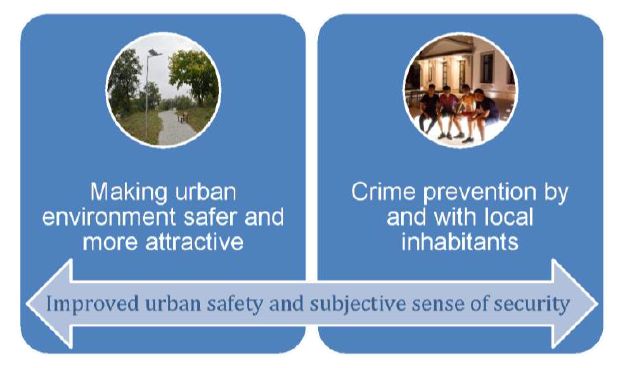

The overall goal of the Szabolcs case study has been to improve urban safety and security as well as the inhabitants’ sense of security in Mátészalka.

Focus areas included:

1) Making urban environment safer and more attractive: Urban planning is a key tool to create a liveable milieu for citizens, thus creative placemaking and urban safety go hand in hand. Urban design contributes to safer public spaces in many ways:

▪ better visibility of places ensures natural surveillance and safe routes for pedestrians;

▪ people use more frequently an attractive, aesthetic, and properly maintained place as a welcoming and inclusive community space, and, in consequence, human presence can keep criminals away;

▪ traffic signs and traffic calming measures have to be clear and unambiguous,

▪ compliance with the rules and community standards have to be regularly monitored.

2) Crime prevention by and with local inhabitants: the overall objective cannot be reached without engaging and involving the users of the city. A strong community shows empathy and understanding, which can indirectly prevent crimes or at least mitigate the incidence of them. Organizations responsible for public safety and citizens have to work together to induce favourable behavioural changes in society.

The key challenge in the city regarding urban safety and security is that some districts and public places are habitually abandoned (mainly from Saturday afternoon to Monday morning). Some of them are underused which deteriorates the cityscape, social cohesion, and local identity, too. This problem occurs primarily in or near the city centre that makes streets, squares, and parks deserted.

The main causes of this phenomenon are

▪ public spaces are not attractive,

▪ some buildings and parks are in poor condition,

▪ public lighting is not effective enough,

▪ relatively low level of subjective sense of secure,

▪ individualized social structure,

▪ relatively low level of social cohesion.

These facts justified the choice of the SSA intervention site which is the so-called Reverence Park near to the city centre.

The title of the SSA was “Improving urban safety in the Reverence Park”. It aimed to develop cost-efficient and climate-neutral public lighting: using solar LED streetlamps together with the additional soft activities. The Reverence Park was revitalized with spatial planning (in the framework of a project co-financed by the EU) such as planting, paving, placement of street furniture and creating a community space. However, the park was underused – mainly in the evenings because of the lack of the public lighting.

The optimal location of the streetlamps was marked by urban planners in September 2021. The awareness-raising event was held on the 13th of October 2021 with the participation of local students, the mayor, URBACT Local Group ULG members, and other relevant stakeholders from the city.

In addition, an easy-to-use e-learning material was elaborated that can be presented in primary schools and high schools of the city to enhance the knowledge and to foster dialogue about urban safety and security in the local community.

Rehabilitation of some districts in an integrated and well-thought manner contributes to the attractiveness and liveability of the city. Design principles were considered that increase also the subjective sense of security among users of the urban space – mainly among local citizens:

▪ ensuring visibility in public spaces,

▪ easy to clean facades,

▪ planting indigenous species in parks,

▪ safe crossings,

▪ using climate-neutral public lighting,

▪ optimal placement of comfortable street furniture.

As a consequence, Mátészalka became a more liveable small-sized city and citizens gained a stronger local identity.

Key partners were: internal and external urban developers and planner, landscape designer, local inhabitants

Another key success factor was related to awareness-raising activities for citizen engagement in urban safety and security.

The level of involvement of local inhabitants into improving urban safety and security is relatively low both in Hungary and in the city of Mátészalka. One of the most important tools is the so-called civil guard system regulated by the Act CLXV of 2011 on Civil Guards and the rules on civil guard activities.

However, it is essential to mobilize social capital among the citizens (e.g. Neighbourhood watch, intergenerational programmes, sport, cultural and other community development events, awareness raising and increasing tolerance and understanding, mentoring, presentation of success stories).

With a higher level of citizen participation, the following results and impact were achieved:

▪ Prevention of becoming of a perpetrator or a victim

▪ Minimising tension within the communities

▪ Building trust, making people feel that their voices matter

▪ Enhancing the sense of sensibility and responsibility

Key activities included:

▪ Identifying local opinion leaders

▪ Creating conditions for communities to participate in the planning and implementation

▪ Facilitating capacity-building initiatives for communities to participate meaningfully

▪ Regular communication with the local community

▪ Organising awareness-raising events among different target groups

Key partners were: police, civil guards, local NGOs, schools, social workers

f. Madrid (Spain) - Safety and security in open public spaces

The addressed security related issue was the massive gathering of young people who meet at specific points of the city for street drinking. This leads to vandalism, fights, deterioration of urban furniture, etc.

To put an end to the nuisance caused by these events and in order to maintain the normal development of peaceful coexistence, a set of integrated activities was considered, namely:

▪ monitoring social media information;

▪ coordinating the various law enforcement agencies,

▪ creating an action plan;

▪ involving citizens in prevention (alerts, warnings, incidents).

Urban dimensions addressed included:

▪ Crime Prevention

▪ Perception of safety

▪ Social cohesion

▪ Governance

Material resources and special equipment adopted, for the scope, include drones, security fences, etc.

Major challenges and risks related to the intervention were the need to reach a suitable level of coordination with municipal services and the extension in several groups with the same origin to other areas of the city.

g. Longford (Ireland) - Using street art to revitalize the city and increase perception

A high-quality town centre can install a sense of pride-of-place and identity within those that live work and use it. Derelict and vacant properties create an intimidating environment, coupled with poor lighting that deter pedestrian traffic and activity at street level.

An attractive environment will increase activity and passive security, particularly in targeted areas. Public and private initiatives and investment have the potential to transform the town core, along with innovative solutions in lighting and wayfinding to secure a secure, accessible and inclusive central area.

The scope of this action was to improve the overall physical appearance of the town centre. Increasing pride of place and an enhanced sense of identity is important to promote passive self-policing of the town centre, making it socially unacceptable to behave in an anti-social way, damaging the reputation of the town, while making others feel safer and more secure.

Well maintained public and private spaces throughout the town centre encourage movement and promote pedestrian activity.

This action was linked to several others designed for Longford within the UrbSecurity project, including urban realm, lighting and landscaping improvements and the creation of a positive perception of Longford from within.

This Action aimed to make small-scale, high-impact interventions in the streetscape to improve the appearance and perception of the town to reduce the impact of vacant and/or derelict properties. Activities included sponsored and private initiatives to paint and repair properties in high profile and blackspot locations, in tandem with improvements in public and private lighting solutions to highlight positive features to encourage activity and passive security.

The specific challenges associated with this action included:

▪ the number of derelict and vacant properties in prominent areas in the centre,

▪ the uncertain ownership of these in some cases, and

▪ the inability to provide beneficial uses for these properties over the last number of years, despite numerous incentive schemes.

Activities deployed included:

▪ encouraging the repair and painting of high profile buildings, walls and structures in the town centre;

▪ continuing the programme of incentives for shopfront improvement;

▪ engaging with local businesses, Community employment schemes, voluntary organisations and other agencies in the public and private sector to maintain public and private spaces;

▪ investigating potential projects and public and private funding sources to progress this action.

The activated support partnership resulted to be very wide, including Longford Tidy Towns, Longford County Council, Education providers, Chamber of Commerce, Business Community/Private investors, Individual Landowners, Arts Community, Community Representative Groups, Revenue Commissioners and Enterprise Ireland.

This case study was closely accompanied and supported by a co-ordinated action dealing with increased perception of the city. Longford suffers, in fact, from a poor public perception in a local and national context. High profile crime stories have created a poor town image and overshadow existing urban assets and good news stories.

Popular and highly utilised amenities should have a higher profile and form a greater part of the identity of the municipal area, as should the high level of community participation and town

spirit.

The scope of this action was to counter this negative perception with positive reporting on activities that build community spirit and outline positive events, interventions and initiatives in Longford Society and how these contribute to a sense of community and pride of place.

Raising a positive profile of Longford Municipality will reinforce relationships between communities and the various agencies that work with them to build positive outcomes and improve an overall sense of security within the town centre.

Building pride of place and an enhanced sense of identity will create self - policing of town centre anti-social behaviour hotspots, making it socially unacceptable to behave in ways that impact poorly on the reputation of the town and reinforce a sense of safety for town centre users.

The specific challenges associated with this action included:

▪ ongoing high-profile feuding activity reported at national level and on social media;

▪ ingrained poor perception of the town centre locally, nationally

Main goals addressed:

▪ a fair and balanced reflection of Longford Town on local national and social media, showcasing its strong community spirit, achievements and the wealth of assets and amenities at its disposal, that welcomes its visitors and is a source of pride to its residents and users;

▪ Longford as a tourism destination, where visitors are instantly aware of and can safely navigate to areas of interest within the town centre.

Activities focused on:

▪ developing a communication programme that promotes positive stories in all communications about Longford, informs the public on positive community relations and associated activities, timelines and tangible outcomes;

▪ regularly updating official Longford social media sites to keep positive initiatives and their impacts alive;

▪ reviewing signage policy to ensure adequate and accessible information and clear signage to Urban assets and highlights at the entrance to and within the town centre.

h. Parma (Italy) - Restoring security perception in city parks

Italy is a variegated country, in which small cities and metropolises of millions of inhabitants coexist, sometimes at a short distance from each other. Each urban agglomeration is the victim of peculiar crimes, which can change the rankings a lot.

The map of crimes in Italy tells how the crime rate in the country had a physiological decline due to the pandemic.

Despite less exposure to crime, two-thirds of Italians fear of being a crime victim remained unchanged from the previous year, less felt less safe while only a few perceived an improvement. In particular, the least confident categories are, on the one hand, those who are in a bad state of health and, on the other, women who perceive an increased fear of suffering theft, robbery and violence.

One of the pictures that will certainly be more incisive is the data on complaints, which probably does not provide a picture of which are the safest cities in Italy, but provides an average of which may be those where more crimes are committed. The map of crimes in Italy then provides the list of the twenty cities where the most crimes are reported: Parma 13th place, stands out negatively for incidence of robberies in stores even in the pandemic time.

Moreover, if once the red zone of degradation was limited to some historical areas such as the one around the station, today the alarm comes from many places, from the outskirts to the historical centre. Groups of neighbourhood watch have been created, especially in the villages surrounding the city, to identify situations at risk and create a stronger network of vigilance among citizens. It's a way to involve citizenship in participatory safety paths. So, residents control their area and report to the municipality if there are problems. The City of Parma, for its part, has decided to increase the network of video surveillance in the hot spots of the city already monitored in collaboration with the municipal police.

The regulatory framework on security has in fact attributed to mayors the task of supervising public order and safety. The mayor, as a government official, contributes to ensuring the cooperation of the local police force with the state police force, within the framework of the coordination directives issued by the Ministry of the Interior. From this framework it emerges that there are specific functions attributed both to the mayor, as an officer of the Government, and to the municipalities, with respect to which they may use video surveillance systems in public places or open to the public in order to protect urban security.

In the context of its institutional purposes, the Municipality of Parma employs the video surveillance system as a tool of primary importance for the control of the territory and for the prevention and rationalization of actions against criminal and administrative offenses as part of the measures to promote and implement the urban security system for the welfare of the local community.

The area covered by this case study, that is the Parco Ducale in Parma, reflects a situation that can be seen in some peripheral areas of the city, as mentioned above, where there are forms of crime, such as drug dealing, theft, but also episodes in which gangs of boys, after targeting minors or defenceless people in areas not passing through and poor lighting, intimidate and rob them.

The actions that were implemented focused on improving the perception of safety for those who frequent the park, so families, young people, the elderly, through a series of actions (improved lighting, video surveillance, new activities etc. ...) that helped people to regain possession of the city park.

As mentioned, the targeted area is the historical Ducal Park, a huge garden on the west side of the river. After the unification of Italy, the Municipality became the owner of the park and opened it to the citizens. The garden walls with its terrasses were demolished and new gates were opened, among which the one on Ponte Verdi, linking the garden to the town centre. A lack of maintenance and an improper use of some areas of the garden have accelerated its decay, leading to a complete restoration works.

This park is in the city centre and so many people grew up in that place. It has a very old structure, with many little corners in which people can hide, people like drug dealers, for example.

The UrbSecurity actions deployed for the Ducal Park had the goal to contribute to the growth of a more liveable place, more objectively safe and smart with the aim of offering the citizen user, families and future generations a greater perception of security.

The main actions included:

PREVENTION AND GOVERNANCE

▪ to reopen one of the gates closed some time ago to facilitate the passage of police cars

▪ to make the police bicycles officers pass through the park

▪ Carabinieri (Corps which have a dual role as a Police and Armed Force) and police officers on leave walking through the park as volunteers

PERCEPTION

SOCIAL COHESION

▪ to involve schools and associations to do sports or organize events: for example, teachers and students of the agricultural school that is attached to the park take care of the maintenance of the planters

▪ Getting people to live in and reappropriate public spaces

▪ Outdoor exhibitions, e.g. exhibitions of murals in deprived or dangerous areas of the city

The actions developed in Parma are different in nature: the first one was an “hard” intervention consisting in a physical investment to make the Park more accessible and controlled, while the second small-scale action was a “soft” and immaterial intervention, being an online survey to users of the Park to better understand habits, usages of the area and gather proposals for improvements.

In an effort to allow better connections between the park and the surrounding district areas, the city administration decided to open a new entrance, by removing a portion of the external iron gate. The new entrance is located in the eastern side of the park, towards via Piacenza.

The change was intended to give citizens close access to the park and improve their usage. Citizens were previously obliged to go around the park to reach one of the other main entrances or other part of the city.

The action included also the positioning of CCVT cameras and of anti-terrorism flower pots at the centre of the entrance aimed at limiting the access to pedestrians, riders and police vehicles only.

Meetings and onsite visits with the Local Police officers, the Superintendence for Historical and Cultural Heritage, the Prefecture, the Neighbourhood Committee of volunteer citizens and the Fire brigades were organised, in order to organise for requests of necessary authorizations, purchase of flower plots and CCTV cameras, positioning of street furniture elements and organising a public event to celebrate the new entrance.

The Ducale Park is now more accessible to the citizens, users and tourists wishing to enjoy the park, and more integrated with the rest of the city.

The new entrance helped also to increase the effectiveness of local police patrolling in the park by providing evidence to relevant enforcement agencies and reassurance to users, preventing antisocial behaviours and reducing the time and distance to get to the park whenever necessary.

As part of the ULG work, the Municipality of Parma agreed also to conduct a usership survey of the Parco Ducale with the aim to address better to community needs, resolve factors of insecurity, identify conflicts among groups of park users, and manage park assets more effectively: all keys to maximizing the security, the safety conditions and liveability of the Ducale Park.

The survey was intended also to collect proposals for improvements from citizens and users and to identify areas and places on which focus ongoing feasibility studies (the Master plan on the Park) and future improvement plans.

Main results were that walking, running, meet friends, bring the children to the playground, and move faster from one side to the other of the city resulted to be the most common reasons to use the Ducale Park.

New suggested potential uses included tourist and historical resource, cultural resource, sport and leisure resource, social cohesion resources.

i. Pella/Giannitsa (Greece) – Safe mobility

The Municipality of Pella covers an area of 668 km2 in the northern part of the Prefecture of Central Macedonia and it is the largest municipality of the wider area.

The safe mobility action involved school students, in cooperation with the municipality of Pella, with the goal to raise awareness regarding the problems that a pedestrian faces in the city.

Students from various classes depicted with the pictures they took around the city, from cases which make difficult pedestrians’ everyday life, commented on them and suggested solutions in order to raise awareness of the citizens and the local authorities.

The result of this teamwork was an interactive book (flip book), promoted and disseminated widely in the city.

The students worked on the action with the title: “Didn’t you see the road sign?” and created an interactive map of the city of Giannitsa, where they focused on points in the city that are considered to be dangerous for the safety of citizens, mainly because of the occupation of the pavements with tables and chairs, stands with products from cafes and shops or illegally parked cars.

This action also depicted some more problems such as erosion of the ground, lack of pavements, stray animals etc.

This map is continuously fed with new data.

A campaign was for the scope designed by the team of the schools in order to raise public awareness and all stakeholders relevant to safety in the city.

Overall, a group of 21 students with their teachers distributed 500 brochures on illegally parked vehicles. The brochure was designed by a student. It’s pretty witty, suitable for the situation. They were all wearing yellow vests and badges representing responsibly their school and their opinion.

They had the chance to talk to drivers and passengers and share their concern about safety in the city and everything related to parking illegally causing inconvenience or possible accidents to the pedestrians.

They noticed that in many streets there were no crossings or they were very faint and were not visible to pedestrians. The pedestrian often cannot cross the road safely.

In many places there are no sidewalks. Pedestrian are forced to walk on the road while putting their life at risk.

On the sidewalks of the city there are many obstacles such as low balconies and incorrect tree planting that make it difficult to move and are the cause of many accidents.

Even drivers often park their cars on pedestrian crossings so that pedestrians cannot cross the road safely. Cars tilt the ramps and make it difficult for people in wheelchairs or mothers with baby carriages to get around.

In many sidewalks there are usually illegal drivers who park their car occupying almost the entire sidewalk affecting the pedestrians to not move easily.

Overall lessons: the drivers realised responsibilities as drivers, students worked as a team (thinking that pedestrian in a humoristic manner do not have wings and drivers should not prevent and disturb mobility of people with certain needs).

Driver awareness campaigns should be organised so that drivers can learn to think about pedestrians.

“Safe parking make safer cities”, this is the driving pay-off.

The action was photographed and filmed by the students as well. It is also posted on the school’s and municipality’s communication media.

A few impressions of the students witnessed the high potential of this SSA:

▪ "I felt that we improved our town. I wouldn't like to become such a driver...."

▪ "I liked a lot the project we did....it had a great impact on us"

▪ "We had the chance to cooperate with each other and learn many things about safety in a city"

▪ "I was impressed by the amount of illegally parked cars"

▪ "I liked the way we dealt with all these drivers"

▪ "As a driver in the future I will try not to make the same mistakes".

5. Conclusions

Based on UrbSecurity case studies and experiences, conclusions and recommendations are derived, matching transnational learning activities with the local level work, inspiring city managers into solutions for focused urban security challenges.

A major conclusion from UrbSecurity is that it is essential and strategic to build on an enhanced and structured transnational and local Action-learning approach: this means better knowledge and skills by working with other cities, exchanging methods and tools among peers and networks, solving concrete problems by designing and testing tailored-made actions.

This enables cities to manage the policy cycle from planning actions to implementing policies, evaluating the results achieved and feeding back the lessons learnt.

Combining local participation with peer learning, a unique chance to co-create and implement new and improved local strategies regarding sustainability of the urban development arise. Through city-to-city cooperation, an effective learning process can be initiated, mutually offering inspiring changes, exchanging good practices and producing integrated plans with local stakeholders and citizens. Such a cooperation facilitates exchange and further implementation and is the foundering aspect of UrbSecurity.

Another key conclusion and recommendation is the need and opportunity to seek for Integrated Action Planning (IAP) co-production, within the so-called Urbact Methodology. The integrated urban development and participative planning are at the heart of the URBACT work and the UrbSecurity activities and findings fully witnessed the validity and potential of this approach. The principle at the basis is that in order to respond to sustainable development issues cities are facing, the social, economic and environmental aspect of a local policy must be considered as a whole, and that such a policy integration can only be done locally, relying on three core concepts: integration, participation, action-learning.

Among all UrbSecurity stakeholders emerged a shared agreement that Political Support is crucial for a successful implementation of any initiative aimed at increasing urban security. Loss of political support is quite common during implementation and IAP deployment, due to a variety of reasons.

Changes in the political representatives (for instance resulting from elections) or slow implementation paths, that can lead to loss of effective political support.

Another key barrier identified within UrbSecurity case studied and that results in a relevant recommendation, is to look for local inter-departmental city collaboration. The implementation of solutions for focused urban security challenges requires in fact collaboration across multiple departments.

The way municipalities are organised does not normally favour inter-departmental collaboration as the work is organised in silos responding to specific areas. However, as many other policies in sustainable urban development, security and safety policies need a multi-dimensional approach, thus requiring the collaboration of different departments (e.g. urban management and social affairs).

But the UrbSecurity major pay-off resulted to be ”Small is good”: the local dimension of the project inspired the designing and testing of Small-Scale Actions (SSA), understood as experimentations limited in time, scale and space, and that proved to be highly cost-effective. SSAs are ideas, solutions, proposals not yet fully tested that the city has interest to implement and test at small scale before embarking on larger scale actions fostering innovation and changes in city administrations.

Ideas for the SSAs come from the city administration in itself, some come from the exchange with other cities during transnational meetings. Being experimental by definition, they demonstrated a relevant potential to generate positive impacts. Monitoring and evaluation of their findings were essential for scaling up them at city and even international level.

Finally, Risk Assessment represents a key management and implementation approach, that should be promoted at city level. Many technological barriers are not fully known in advance. Some constraints are only identified during implementation.

This is the reason why a continuous risk assessment activity should be ensured, using a sort of “Viability Check” on every project or action that promotes any change of the public and living space.

It should take duly into account the demographics of the area and other relevant data to “test” the solution together with stakeholders, even prior to implementation, and to supervise activity deployment, impact assessment, and prepare the field for replicability and transferability, that represent the core scope of the whole UrbSecurity initiative.

Elaborated by:

Pedro Soutinho (Lead Expert)

Alberto Bonetti (Ad-hoc Expert)

Contributors:

Luis Pinela; Vitoria Mendes, Maria J. Vasconcelos (City of Leiria, LP)

Javier Castaño, Frederico Uría (City of Madrid; Municipal Police)

Aoife Moore; Lorraine O’Connor (City of Longford)

Erwin Coeman; Steven Van Haegenberg (City of Mechelen)

Anastasia Herk (City of Giannitsa)

Monica Visentin (Unione de la Romana Faentina)

Jana Machová; Martina Danková; Maria Holanova (City of Michalovce)

Ivano Dinapoli (City of Parma)

Anett Bauer; Monika Komádi (Szabolcs 05 Region; City of Mátészalka)

2022 © UrbSecurity APN

Submitted by Patricia Moital on