URBAN MAPPING: MURCIA COLLECTIVE CARTOGRAPHY IN SANTA EULALIA PART 2

Edited on

02 October 20181. INTRODUCTION

As we mentioned in the previous article, the use of urban mapping as a methodological tool for obtaining an associated map of the Santa Eulalia neighbourhood allows the extraction of valuable data that need to be collected in a citizen participation process as extensive as this one whilst being replicable and enriching proposals of other (possible) urban interventions.

In the previous article we included the methodology we are using and the analysis of the neighbourhood we carried out together with people with disabilities, elderly citizens and children. This article on the other hand will focus on exposing the work we have done with the remaining groups, as well as a reflexion on the process and preliminary conclusions we have gathered.

You can read the previous article here: URBAN MAPPING: COLLECTIVE CARTOGRAPHY IN SANTA EULALIA PART 1

GROUP 4: Young university students

The space we have chosen for the urban mapping with university students, was the very courtyard of Murcia University. The University and the collective of university students has special relevance within the neighbourhood, a characteristic which makes it a neighbourhood with a strong identity within the city, an identity that must be respected and cared for. Meanwhile we are aware of the processes of gentrification that have affected neighbourhoods around the world, making them elitist and exclusive, in many cases combined with the "artistification" of the neighbourhood.

|

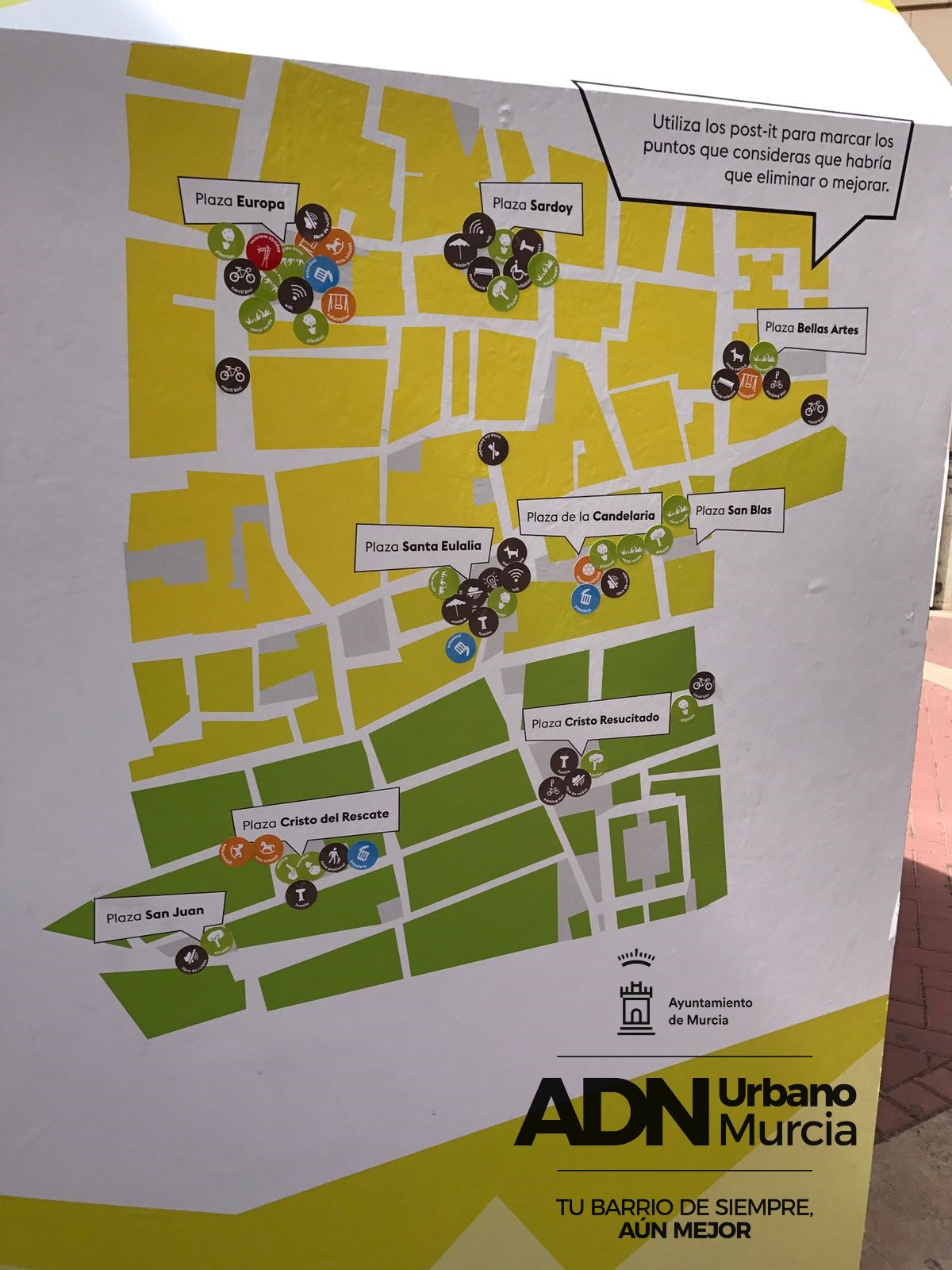

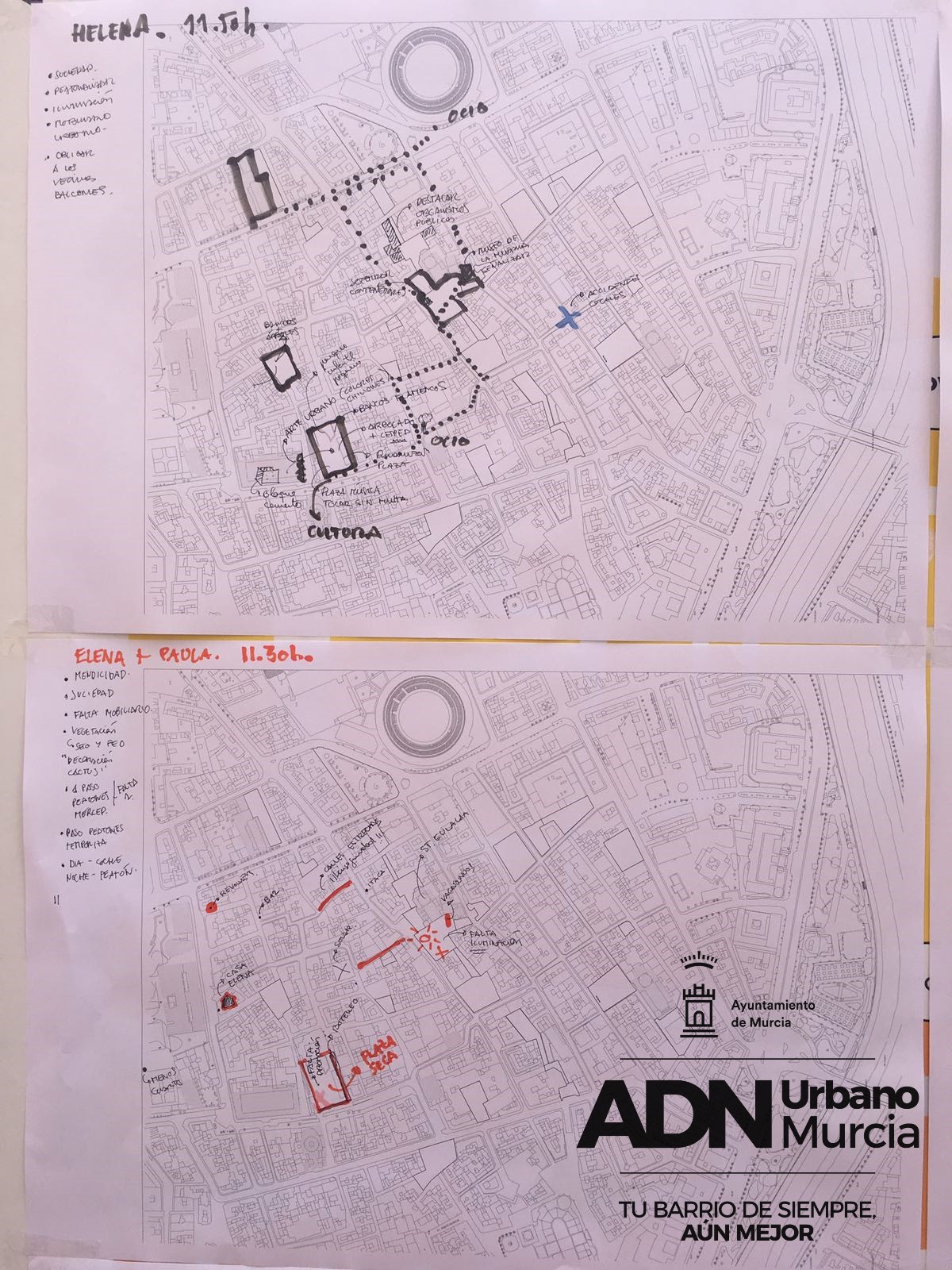

On this occasion, we proposed a different approach; A hybrid methodology between the conventional cartographic mapping of the neighbourhood in which the demands of the participants are reflected, and a system of stickers. These are small circular stickers that indicate new possible uses (green area, playing space (kids), street furniture, fountains, etc.) that participants can place on the spaces they select. It is a very direct and agile way of participating that gives us a quick and graphic overview of those spaces requested most or "black areas". If in a specific place there is an overlapping of numerous stickers, we can deduce that there is a considerable demand for improvement. This is the case of some places (squares) like “Plaza de Europa” o “Cristo del Rescate”.

At the same time as the sticking of the stickers, on a different map of the neighbourhood participants draw and write down observations, suggestions and demands that arise from the conversation/debate and which participants could not adequately reflect by using the system of stickers.

|

Finally, from the overlap of results between the two participation systems, a cartography very rich in information emerges, which allows us to detect spaces or areas with a greater demand for improvement.

GROUP 5: Owners of bars which have terraces in the squares of the neighbourhood

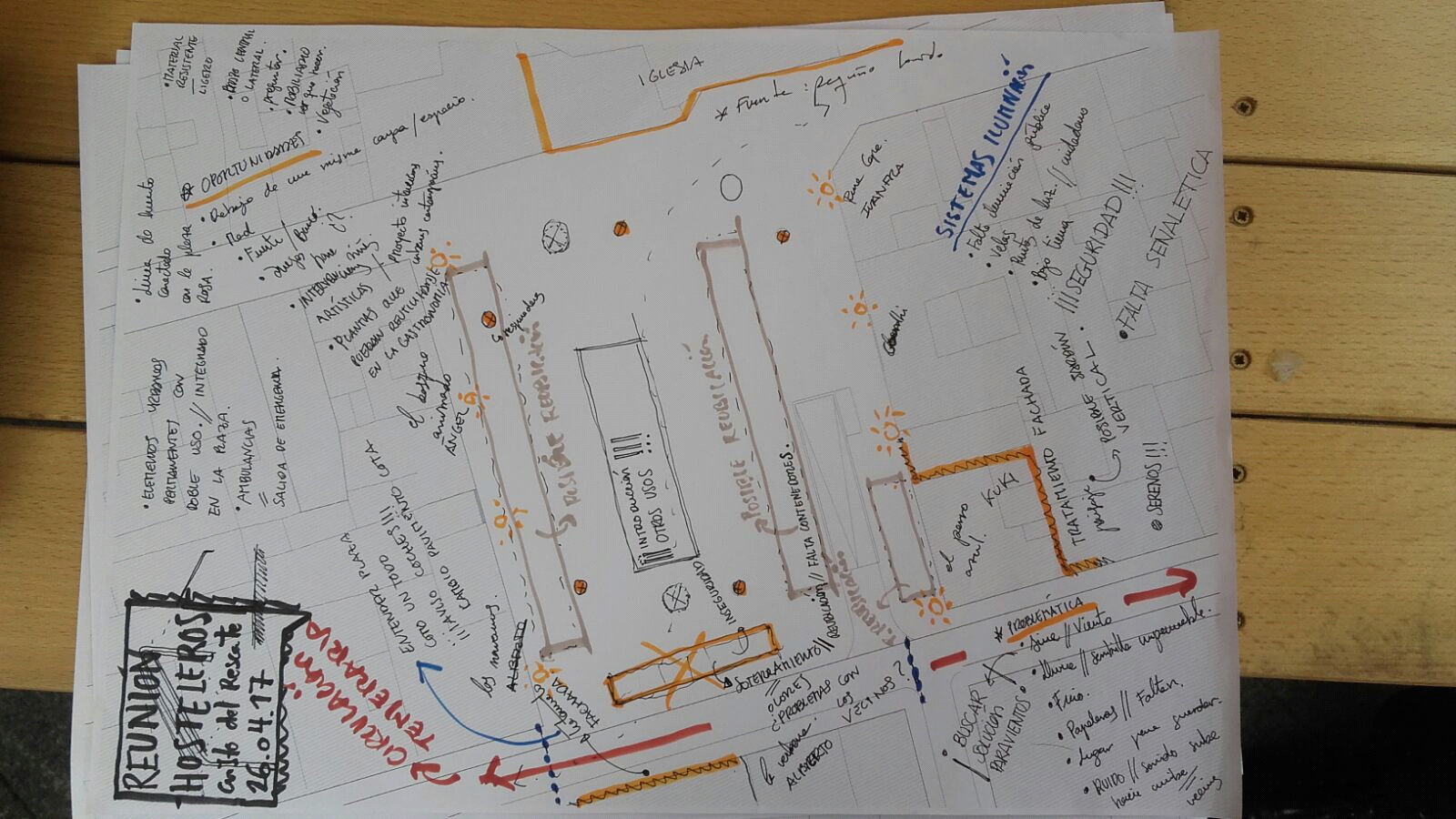

This group is quite different from the previous ones due to several factors. Both places where the mapping took place --Cristo del Rescate & Cristo Resucitado-- are spaces which have been heavily invaded by (private) terraces of the bar owners, not complying with (parts) of current regulations and legislation, turning them into places where the urban quality and the existence of a comfortable public space is reduced.

In this context, there is a need for redesigning the squares and the present elements in them, including the terraces, and with the active participation of the owners of the bars that are located there.

|

As a work methodology, we decided to hold a meeting in each square with the owners of the establishments and simultaneously addressing various topics -terraces, new uses for the square, specific needs, suggestions, etc.- recording testimonies and drawing on a map of the square, joining all the observations and proposals.

At the end we agreed upon a proposal for the design of both squares with this group, but without forgetting that the experience that is sought should be as complete as possible, and the fact we need to add the other mappings that have been made with the rest of the groups to this outcome, as the other participants have also communicated their opinions and demands for the same space. All this information will feed into the proposals put forward at the end of the process and prior to which an exhaustive analyses will be carried out by the multidisciplinary technical team that addresses the urban interventions.

|

CONCLUSIONS

In general, we can state that collective urban mapping is a very useful tool in urban design. In the first place, because maybe, as experts, we think we know the answer to every problem, through our education and experience, a concept that is quickly dismantled when observing the inhabitants of the neighbourhood during the walks, conversations and mappings that have been carried out. The residents are fully aware of their needs and propose very specific improvements. Their opinions and suggestions quickly become valuable information that makes us understand the context and use of the urban landscape, they see issues and problems, we would not be aware of if we only used a conventional urban analysis, on a map and from an office.

One of the aspects we believe to be of great relevance is the very sense and judgement of the demands expressed by the groups. These are not necessities that require an exorbitant budget or big structural interventions, all groups repeat and signal basic issues that would improve the quality of life in the day to day life of the neighbourhood: trees, level streets and squares, play spaces for children, areas to rest and shade, fountains, opening lots that let people breathe and that augment the public space available in the neighbourhood, etc. Small interventions, an urban acupuncture of sorts, of which the favourable impact on the quality of life found in the neighbourhood, would be immediate. We also note that the demands coincide in 90% with those observations detailed in the previous analysis "Physical study of the area as a whole".

RISKS INVOLVED

As we know, it is a process in which many neighbours are involved in the hope of addressing those issues they are concerned most, some of which they have been signalling for years. In this context, it is important not to guarantee or assure any solution to their demands as it could cause discontent and distrust in the other groups.

In this sense, a balance is sought that allows us to obtain information, whilst making it clear that not everything can be solved, and that it is a process that will be extended in time, but that it is important to start somewhere.

Even so, we are convinced that these processes must be documented with the seriousness and quality they deserve, without being used (only) as propaganda and media exposure, but as a possibility for the real integration of the citizens in the decision making process for their own surroundings, accompanying them and providing creative and competent experts that enrich the process and answer their questions.

We consider these processes of citizen participation for decision-making in concrete contexts, as well as a valuable tool for urban design a good way to start and gather information in a relatively short space of time.

AUTHORS

Dictinio de Castillo-Elejabeytia Gómez, Carlos Pérez Armenteros

VERBO Estudio (April 2017)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Koolhaas, Rem. “La ciudad genérica”. Ed. Gustavo Gili, S.L, Barcelona, 2006.

- Augé, Marc. “Los no lugares”. Ed. Gedisa, S.A, Barcelona 1998.

- Cano Clares, José Luis. “Plan general de Murcia de 1978”. Ed. Diego Marín, Murcia, 2005.

- Cano Clares, José Luis . ”Ciudades. El arte urbano”. Ed. Diego Marín, Murcia, 1999.

- Vinuesa Angulo, Julio. “El festín de la vivienda”. Ed. Díaz &Pons S.L, Madrid, 2013.

- Alarcón, Tomás. “Murcia Antigua en fotografías”. Tipografía Guirao, Murcia, 1985.

- Gehl, Jan. “La humanización del espacio urbano”. Ed.Reverté, S.A, Barcelona, 2006.

- Museo nacional Reina Sofía. “Playgrounds: reinventar la plaza”. Ed.Siruela, S.A, Madrid 2014.

-Jacobs, Jane. “Muerte y vida de las grandes ciudades”. Ed.Capitan Swing, Madrid 2011.

-Tonucci, Francesco. “La ciudad de los niños”. Ed. Graó, Barcelona 2015

ARTICLES

-García Pérez, Eva. “Ciudad árbol, ciudad Flexible y ciudad No Subjetiva”. Ed. Urgente, no.7, Madrid 2005.

-Barba, José Juan. “Genereic and Queer city”. Ed. Formas, no.17, Madrid, 2007.

-Barba, José Juan “La ciudad contemporánea”. Sp. Illuminosis*en el espacio público, 2013.

-Alexander, Christopher. “La ciudad no es un árbol”. Berkeley, 1965.

Submitted by fvirgilio on