ReGeneration and the inter-generational approach

Edited on

09 March 2017Initial reflections on the implementation network challenges after first visits to the partner cities.

Urban regeneration requires a combination of spatial, social and economic change. The necessity of developing an integrated approach for urban regeneration has become an aquis of European policy making, but the challenge to maintain its principles in the implementation of concrete actions is still an open issue. The ReGeneration implementation network starts from this ambitious challenge to explore a complex theme: how to limit land consumption and promote the best use of natural and cultural resources, and how to do it activating the exchange between generations as an essential key to enhance the transmission of ideas, resources and responsibilities?

The network has declared its objectives in a clear sequence:

- Regenerating places: fostering efficient use of natural and built resources to counter land consumption, responding to the environmental dimension of sustainability

- Regenerating communities: enhancing the potential of social capital, inventiveness and motivation stemming from youths, as a key requirement of social sustainability.

- Regenerating resources: innovating project financing to achieve economic sustainability and enhance circular, commons based economies.

Such a consequential set of goals combines in the overall challenge of traducing strategies that on paper are integrated into effective action. That means, ultimately, delivering policy innovation.

The ReGeneration network has identified in the inter-generational approach an essential response to the necessity to renew policy making and territorial governance. Young generations are the bearer of fresh energies and innovation capacity, but they also are those that will ultimately inherit the effects of today’s policy. Their participation in the revitalization of urban territories is a precondition to guarantee their sustainable development. Their involvement is essential to invest on innovative financial and management strategies to produce long-term effects on the urban economy.

The network of seven partners presents very diverse profiles, strategies and objectives. They are hardly comparable in dimension, in political culture and governance patterns. Rather than a problem, this constitutes an opportunity to understand the transversal nature of the issues in discussion, confirming how despite the different contexts such issues are throughout Europe extremely relevant. The collaboration between the partners is at a very early stage, but the first two visits produced already a great deal of ideas and suggestions. I will refer here in particular to the second one to Ercolano, a town in the metropolitan area of Naples, a visit that has been very helpful to delve into the many implications of the regeneration discourse.

Ercolano, the wealth of the heritage or the burden of the past?

I take the cue of my reflection from this freshly visited city. While I write, I am still full of impressions and emotions mixing up professional and personal life, and I will allow my personal life mixing up with the case study, I hope for good. It happens by chance to me as the lead expert in charge of following this network to be incidentally born and grown up in Ercolano. My family left the when I was 17, and I barely visited the city since then, actually not anymore since more than 30 years. What follows draws on the cognitive gap between my perception as a teenager from Ercolano in 1980 and the professional urbanist and euro expat of today. My family moved essentially out of the concern to give a better future to their children. My experience as an Ercolanese is quite typical, many of those I knew at that time have left, and in my living and traveling abroad I have often met young people emigrated from Ercolano. My remembrances of the place were mainly connected with frustration, degradation of environmental conditions and a feeling of no hope for local society. During theses two days in Ercolano no one of these feelings was completely deceived, but at the same time I was stunned by the extraordinary cultural and aesthetical qualities of the city and by the potential in productive and economic terms that the city owns, although leaving it in great part unexpressed.

The view from the Vesuvio

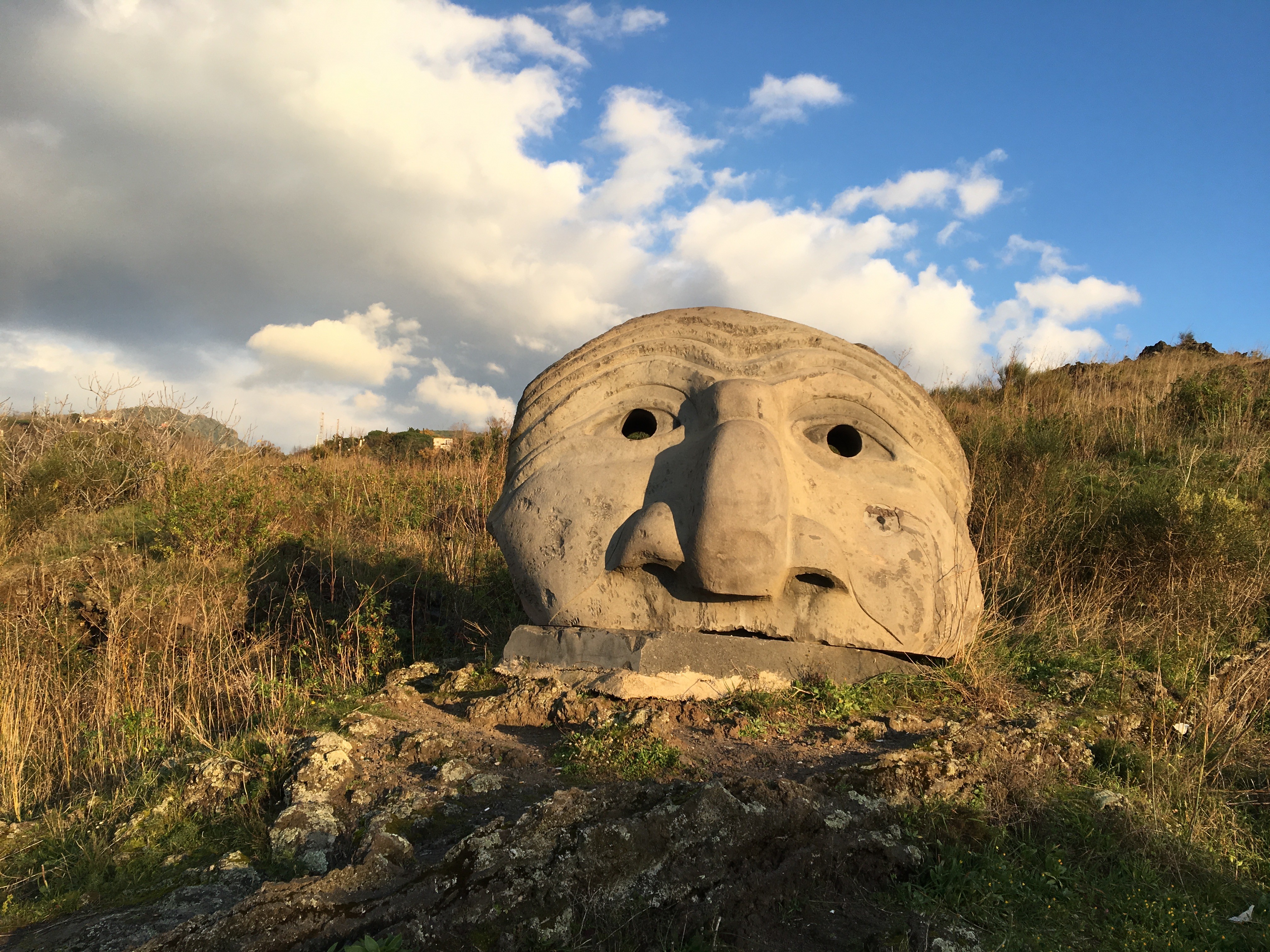

Our visit starts from the top, up the iconic volcano dominating the city, immersed in the national park that has its main access in Ercolano. The city under us is a narrow strip form the mountain to the sea. The Town Planning Councillor Giuliana De Fiore shows us with motivated pride the improvement made to the street climbing to the mountain, now punctuated by a series of sculptures in volcanic basalt commissioned to local artists. The Municipality plans to set at the beginning of the park a new parking area connected with a sustainable public transport system, including recovering an old light rail, to substitute the private mobility often congesting the path. It is one of the many projects that the new administration has devised but struggles to bring into implementation. In front of the wonderful view on the gulf of Naples, with Capri and Ischia in sight from the top, the administrator tells me that the extraordinary value of the territory represent also a burden in terms of operability. It is charged in fact by all possible type of restrictions due to environmental, geological, heritage, natural qualities of the territory. It is in the center of a territory at high-risk for seismic and volcanic activities threatening almost a million of inhabitants in the surroundings. It has a huge archeological area, a rich architectural heritage, natural parks, and a sensitive coastal line. One effect is that implementing urban developments becomes an almost impossible task amid a jungle of restrictions and agencies in charge of policing the different sectors. Consequently, the praxis of abusive development in the booming Neapolitan suburbs has been a constant in the post war until recent times, leaving all over the territory a huge amount of illegal properties in need to be regularized or disposed.

Connecting the Scavi di Ercolano…

Getting down to the city, we pass through via IV Novembre, the main transversal axis that connects the Station of the Circumvesuviana train with the site of the ancient Herculaneum, one of the most extraordinary archeological sites of the world. Covered by the ashes of the 79 AC eruption, it is on of best preserved Roman cities, a almost unique heritage site which lays in the very heart of the city. The boulevard has been recently refurbished with finely designed urban furniture and curbed threes outlining the perspective that through the archeological site goes to straight the sea.

On one side a former school as been transformed in the MAV, Virtual Archeological Museum. The transversal Corso Resina, the main road that connects Napoli to Pompei and Sorrento is in this section named “The Golden Mile” as it concentrates a number of Eighteenth century Villas of exceptional architectural value. I can still remember these as Piranesian ruins in the landscapes of my childhood. Today they are for the most restored and look gorgeous and cared. Still they are often underused or badly managed, as in the case of a luxury hotel implanted through PPP with a local entrepreneur that is badly performing economically and underrated.

… and the seaside

The final stop-over of our tour is on the seaside. After years of environmental emergency, the drainage system of the city has been recently connected to the main Neapolitan collector, and the sanitized coastline can be recovered for public leisure purposes. The seashore is unfortunately cut out by a coastal railway, connected by few low passages. The project of recovering the coast is part of a metropolitan strategy set at national level by the ministry of Culture and Tourism (MIBACT). The Grande Progetto Pompei is a strategic plan aimed at systemically connect the sparse cultural and archeological resources part of the UNESCO patrimony along the coastal line. It foresees a number of pivotal projects in Ercolano: the opening of a new Railway station, the restoration of Villa Favorita park , improvements in the Herculanum site, and the above quoted interventions to connect the Vesuvio National Park with the tourism flows of the archeological site.

It is from this strategic document that Ercolano will start its challenge within the URBACT implementation networks. There is the need to design an action plan connecting the diverse interventions in an implementation framework, but also to form new competences and to foster a culture of participation of the society at large in order to achieve a systemic change. The administration is new and dynamic but inherits the burden of decades of inefficient and often corrupted government of the territory. Just to add on this scenario, the development of a new master plan was blocked during the previous administration due to legal-procedural issues, and still today planning permissions must refer to a 1975 old and obsolete Piano Regolatore. In a similar condition to implement actions as an exception to or in absence of updated regulations requires a leadership that can be only built on consensus and civic participation. Positive signs of change are evident over the territory and are perceived by the population. Physical regeneration has started and delivered several visible outcomes in terms of facilities and infrastructure, but effective capacity to leverage positive change in the social and economic sphere has still to come. The risk is to see the investment on these regeneration projects wasted, resolving ultimately only in next burden for the public sector to counter their physical decay.

Discussing with the members of the Ercolano ULG the reasons for the chronic incapacity to escape the downward spiral of abandonment, missing self-confidence and fatalism characterizing the socio-political landscape, one recurrent argument has been the lack of continuity between generations and education of the new ones. It is an issue that takes a variety of forms, from the ageing of civil servants, whose turnover is impossible due to the Stability Pact, to the fact that Ercolano has a particularly underdeveloped situation in terms of education, missing any high education institute despite a population of more than 50.000 inhabitants. Ultimately, the extraordinary cultural wealth, mostly consumed as a commodity for short-term visitors, is hardly able to constitute a real resource for the growth of local society.

Discussing with the members of the Ercolano ULG the reasons for the chronic incapacity to escape the downward spiral of abandonment, missing self-confidence and fatalism characterizing the socio-political landscape, one recurrent argument has been the lack of continuity between generations and education of the new ones. It is an issue that takes a variety of forms, from the ageing of civil servants, whose turnover is impossible due to the Stability Pact, to the fact that Ercolano has a particularly underdeveloped situation in terms of education, missing any high education institute despite a population of more than 50.000 inhabitants. Ultimately, the extraordinary cultural wealth, mostly consumed as a commodity for short-term visitors, is hardly able to constitute a real resource for the growth of local society.

An intergenerational approach?

Such a mix of extraordinary opportunities and missing capacities provides a good field to start a reflection for the network of cities that joined ReGeneration. The very concrete aim of regenerating physical structures is inescapably connected with the necessity to regenerate past models and activate new energies. Cities offer a great potential as a place to grow together, but such geographies of exchange and innovation need to be activated in a multi-scalar effort. A similar challenge is for instance shared by the first visited partner, Bialystok, Poland, despite the two settings could not be more disparate. There, the partner is an association of Municipalities formed expressly with the goal to implement an Integrated Territorial Investment, an innovative EU funded tool to deliver integrated strategies. Environmental and heritage restrictions are far less relevant, and the general governance framework less complicated in Bialystok. Even the theme of limiting land consumption appears less crucial in a territory with a low-density urbanization surrounded by vast rural areas. But when we got to discuss the issue of mobilizing young generations to generate innovative capacity, to transform abstract invocations of participation into effective involvement and exchange of knowledge between generations and social groups, the considerations of the two partners were strikingly similar. Across the different challenge characterizing all the seven partners, the “learning city”[1] theme is emerging progressively as the connecting common thread. From schools and educational structures, playground and sport facilities, to incubators and co-working spaces, the geography intergenerational exchange is not simply a sectoral service for limited groups of users: these are the key places in which the local society can breed the seeds of sustainable development. Starting from the experience of the lead partner San Lazzaro di Savena, which is centering its implementation challenge on the Campus Kid, a multifunctional area concentrating structures for education and sport, a main focus of the network will be on how to identify and activate multifunctional areas that not simply provide specific services for education and care of specific age ranges, but can become catalyst of intergenerational exchange, social innovation and participation at large.

[1] I refer here expressely to the experience of Robinsbalje, Bremen’s Learning Neighbourhood and the previous experiences with Groeningen „Learning Windows“. http://www.aeidl.eu/en/projects/territorial-development/urban-development/urban-projects/1153-robinsbalje-bremens-learning-neighbourhood.html

Submitted by Lorenzo Tripodi on

Submitted by Lorenzo Tripodi on