Essential Elements of the Baseline Study

Edited on

07 September 2016OUR COMMON GROUND – ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF THE BASELINE STUDY

1. Being close to the citizens: "It is this "people power" (Adams 2014) which is based on a real collaborative model, but where at the same time social entrepreneurs play a new role, not dominated by profit, but having the ambition to tackle poverty and inequalities, and the new role of local authorities "enabling, supporting and providing the trust that acts as a glue in collaborative settings".

2. Common concepts: collaborative meeting places, the will to listen, building common appreciation of values, new connections, sharing knowledge, creating a good context, or ecosystem, emancipation or empowerment of individuals, highly disruptive/ uncomfortable. As remind us Bosschart & Biemans (2015): "Change on a local level is already possible today. Right now. Since there is no 1 central approach, every new initiative will have the character of an experiment."

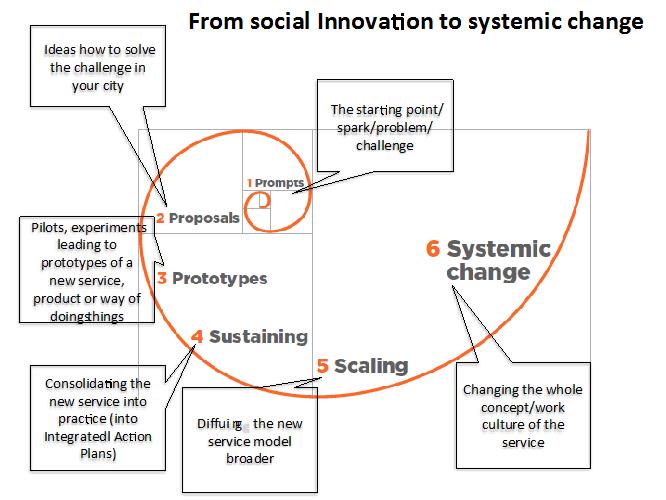

3. The Young Spiral and the role of local authorities:

The role of local and regional authorities is vital and should lead to the creation of a systemic acceptance of social innovation within the boundaries of the public good, of which the guardian must be the locally elected authority in partnership with its citizens.

A. Pugliese - Rome Impact Hub

4. How do we work towards an eco-system? Creating an eco-system for SI implies focusing on the interaction between citizens and their context. As we know planning suffers from a temporal lag (it takes time to plan), and the challenges our cities have stimulate initial responses (almost at once). Therefore an iterative approach which is non linear should be appropriate, allowing for failures on the way. We must remember that the plan is to find RESPONSES to produce good interfaces with citizens, their capabilities and their innovations!

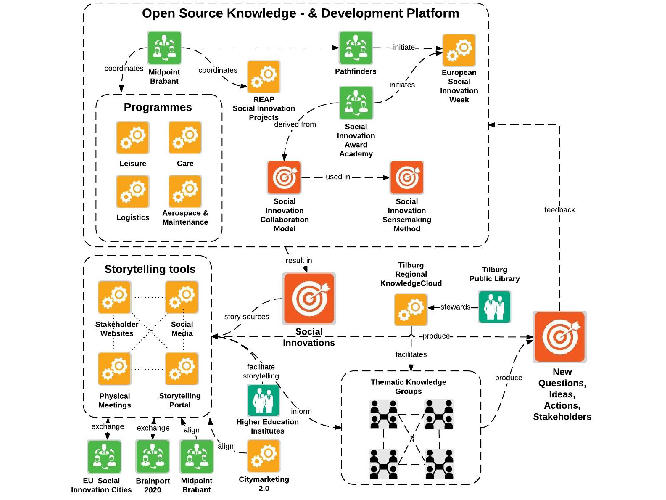

5. Territories and storytelling and…:

SI takes place on a given territory, where we have numerous actors. Organising them is the key to success, but they should in-clude groups which can reflect, libraries which can collect, stock and communicate, social enterprises which can do, events which showcase the successes, and many other functions, which strengthen local communities and allow SI to mature because citizens' freedom is so advanced that creativity and responsibility become permanent features of the landscape.

6. A LONGSTANDING INNOVATOR:

Social and solidarity economy structures have proved their capacity to innovate in many circumstances. They should remain as the nucleus of social innovations, but must work and be open to all the other partners. Their capacity to break out of the local eco-system and to strengthen their business by going to other towns, exporting abroad, or organizing a franchise system are keys to the success of SI.

7. SOCIAL AND FINANCIAL IMPACT MEASUREMENT;

NESTA (UK) gives us the following scheme, but other tools will follow and will have to be worked out by our network.

- Level 1: You can describe what you do and why it matters, logically, coherently and convincingly,

- Level 2: You capture data that shows positive change, but you cannot confirm you caused this,

- Level 3: You can demonstrate causality using a control or comparison group,

- Level 4: You have one + independent replication evaluations that confirm these conclusions,

- Level 5: You have manuals, systems and procedures to ensure consistent replication and positive impact.

8. SOCIAL INNOVATORS –> INSTITUTIONAL ENTREPRENEURS;

According to Frances Westley social innovators in an administration become institutional entrepreneurs, as they introduce innovations, manage the broader context “in such a way that the innovation has a chance to flourish, widening the circle of its impact” and „aspire to cross scales and move social innovation from one level to another”. To do this we must have the following skills: cultural and social skills (cognitive, knowledge management, sense making, convening), political skills (networking, advocacy, lobbying, coalition building) and resource mobilization skills (financial, social, intellectual, cultural, and political capital). Meaningful change has to be brought about through simple straightforward methods, on local scales, with the possibility of transfer, as the large scale efforts are more and more difficult to adapt to local needs.

In Italy the Avanzi organisation has defined the characteristics of social innovation, with a methodology that may be used in the whole country:

AVANZI: Signals of the future

Bottom up innovations to be mapped in Italy

1. Difficult to classify. The most interesting social innovations are a combination of markets, services and approaches and do not belong to a specific sector. This happens for social agriculture, educational manufacturing, hybrid spaces, collaborative services in hospitality, social streets and so on.

2. Creative destruction. The economic crisis has accelerated innovation processes and opened up business opportunities in different fields. These emerge from the retreat of welfare state, but also because opportunity costs and risks for entrepreneurship have changed, in relative terms. In the social business area, this trend is significant and visible and a new wave of entrepreneurs have entered into the social business domain.

3. Civic passion. When it comes to social business projects, the idea is often very much connected to personal experiences and problems. Social innovators have discovered that an enterprise is a framework, an infrastructure and a tool to solve significant issues and to empower civic passions. This represents a significant cultural shift, compared with decades when companies and social benefits have been considered incompatible.

4. A new type of business. These motivations are suggesting that a new form of capitalism is emerging, where profits are purely instrumental and impacts or benefits to the society are the main objectives of doing business.

5. Together. The "social" dimension of innovation is twofold: on the one side it is referred to the social benefit and the social issues the product/service (or the organisation itself) is aiming to solve. On the other side it may be referred to the collective action of doing, of experimenting, of designing and validating new ideas to tackle social issues.

6. Less is more. Various projects are reusing, with creativity, material and immaterial resources, including abandoned spaces, wasted materials and energy, but also know how, experience and so on. This trend is not only related to scarcity and the economic crisis; on the contrary, in many projects a new aesthetics and culture of upcycling is emerging and the exchange value of products and services is directly connected the ability of innovators to transform existing assets into smart responses to societal needs.

7. Coming from conflict. Various innovations emerge from conflictual situations, such as house squatting, large migration flows, boycotting of retail chains, environmental disasters, land use, and so on. Conflicts have the power to stimulate and test new ideas, to consolidate networks, to attract interests and to pave the path for side innovations. But when innovations move into the (social) business domain, other conflicts emerge, where the discussion between profit and non-profit and, more broadly, volunteering and professional nature of people's efforts may become contentious.

8. Innovating by doing and by interacting. Not a new adagio for innovation processes, but a particularly true dynamic for social innovations, where the technological and technical nature of innovation is less important than in other fields. Social innovators continuously interact with users, clients and other stakeholders as part of a way of living and acting, and not only as an explicit design discipline.

9. Identity. Social innovators are more entrepreneurs than employees. A part from the contractual arrangements that regulate working relationships (but also in a framework of volunteer contribution), they take risks, they work for a while without compensation, they pivot services and business models in order to find more effective and efficient ways to respond to user needs. These are clearly features of an entrepreneurial approach.

10. Legal forms vary from informal groups (permanently to temporarily informal) to associations, foundations, cooperatives, traditional businesses and more. The traditional legal forms for social innovators and businesses appear obsolete, together with the dichotomy between profit and non-profit.

Submitted by BoostINNO on

Submitted by BoostINNO on