Malbork and Cesena. Working with heritage differently - by Lead Expert Miguel Rivas

Edited on

23 June 2022Small and medium-sized cities finding their niches and potentials. That was the subject of one the sessions at the URBACT City Festival held in Paris in June 2022, with the contribution of the KAIRÓS network. Indeed, KAIRÓS´ value proposition is that a broader conception of heritage valorisation can make heritage work more massively as a driver for sustainable urban development; and this is largely about to take full advantage of two major changes that are impacting the heritage field over the past years.

Change of scale and change of purpose

The first major change in the field of heritage management is a change of scale. The spotlight is not so focused now on the single building and the monumental artefact, but also on the urban fabric. It has led to a number of emerging concepts, such as historical urban landscape, urban heritage and heritage city. The second and most importantly is a change of purpose, meaning that valorisation matters as much as preservation nowadays. Valorisation means giving cultural heritage a new life or enhancing it, in terms of use and function. Thus, rather than a stock of the past, heritage is now addressed as a history of transitions —living memory— therefore also valuable to make the contemporary city.

In other words, when it comes to re-examine their potential for (sustainable) growth and enhance their positioning in the European urban landscape, small and medium-sized cities should expand the way they are addressing their built heritage. It leads to make a bridge between the cultural heritage field (which usually lacks urban culture) and the field of urban management, which at its best looks at heritage as a tourism asset and sometimes as an unavoidable obstacle to making the city. In the frame of the KAIRÓS network, two cities are working in this direction, to tackle very different challenges each.

Malbork: strengthening a city perspective to heritage

Everyone in Poland and many in Europe know Malbork (40.000 inhabitants) as home to the impressive Teutonic Castle, which is UNESCO World Heritage and one of the most visited sites in the country. However, the City feels the impact on the local economy of the massive inflow of people, who mostly visit the castle for some hours and then leave the city, could be higher. On the other hand, Malbork is close to Gdansk conurbation (800.000 inhabitants), which is a magnet for the young population of the Pomerania region. In this context, the Local Government is trying to re-think cultural heritage from a wider city perspective, beyond its main monumental artefact and the tourism framework, in order to fully realize the potential of heritage as a driver for the city development. This entails opening three ambits for discussion and action.

- Urban space, which is hurt and fractured by two national roads and the railway line that cross the city. Giving an instrumental role to concepts like cultural urban landscape or urban heritage could contribute to “sewing up the city” and overcoming the different segregated spatial dynamics, by promoting new circulations for both visitors and locals. Circulations inside the city —through a renovated approach on heritage valorisation— and those of the city to the Nogat river bank and the countryside —by linking heritage and nature.

Flagship projects on heritage valorisation and adaptive reuse will be able to work as landmarks along those new circulations. Both existing projects —e.g. Malbork cultural and educational centre at the Latin School, Water Tower— and others to come —Old Town Hall, 19th century style mansions, etc. In this context, even there might be room for some of the existing projects to refine on their repurposing programme —e.g. the Latin School going beyond education and cultural animation to host an Urban Lab, with the aim to explore the many possibilities behind the idea of heritage-driven urban development and regeneration.

- Innovation and entrepreneurial trajectories. A broader understanding of heritage valorisation is a source for innovations and business opportunities, ranging from digitisation to new ways of heritage experience —VR/AR, gamification, 3D modelling, IoT, AR-based app development, crowd analytics, new urban lighting, etc. Not to mention that historic quarters usually work as the perfect setting for the local creative ecosystems, according to Jane Jacobs's famous insight saying that “new ideas need old buildings”. This could feed a clearer value proposition of Malbork as local economy, in order to target people and investment differently, including heritage-based investment attraction.

- Strategic communication. In the sense of promoting a more integrated approach to branding & marketing Malbork, in a way that the castle does not overshadow other real and potential city assets. This new integrated approach will enable targeting other audiences different to visitors. For instance, Malbork as the best choice to live within the growing Gdansk city region, at an affordable cost, in connection to heritage and nature, and easy to commute with the Tricity agglomeration.

In short, the above is about adopting a modern view of heritage management, more closely related to urban futures, in terms of social accessibility, innovation & entrepreneurship and urban planning, and duly translated in terms of branding and communications.

In this regard, it is worth bringing the case of Óbidos, a municipality of only 10.000 inhabitants located 70 Km North of Lisbon. It is the quintessential small heritage city, somehow similar to Siena in Italy. They have many visitors every year who stay for some hours, but they are not interested in being a touristic city only. Instead, the City created a value proposition around the overarching idea of “creative innovation” and started to work in that direction systematically. It included a good number of heritage adaptive reuse projects and campaigns targeting young talents and start-ups from the Lisbon agglomeration, offering them relocation packages. Today, besides its heritage, Óbidos is widely acknowledged as an innovate city in Portugal.

Cesena: this is not about historic centres only

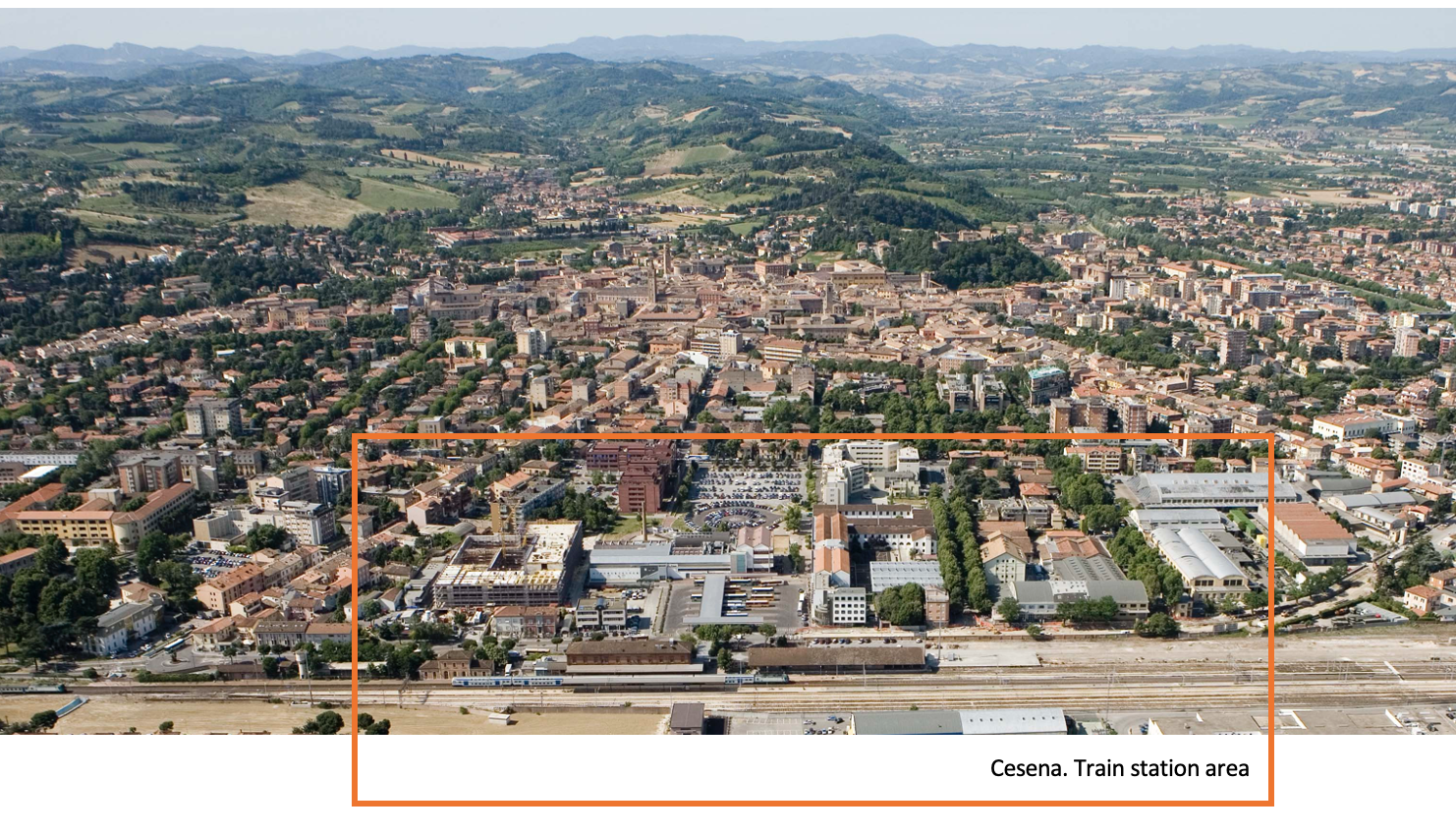

Over the past years, the Municipality of Cesena has been developing an impactful strategy on heritage-led urban regeneration and heritage valorisation primarily focused on the historic centre. At present, the main city project is nonetheless about reactivating the industrial legacy and memory of the city as foundation for the redevelopment of the now flat and characterless train station area, like many other areas surrounding train stations.

The industrial memory is that of the Arrigoni complex, a fruit and vegetable processing factory that reached its peak during the war period. The Arrigoni became popular bacause many of its workers fought fascism with strikes and sabotage actions, so many were persecuted or killed, including the owner Giorgio Sanguinetti. During the 60´s the plant was moved to the periphery, freeing up a large area which was redeveloped 20 years after. Today, a few buildings and one of the 3 big chimneys of the former factory remain.

Although the area is home to three high schools and the faculty of psychology, it is undergoing urban and social decay, with abandoned spaces and lack of quality public spaces where to stop while waiting for the train, as well as facilities dedicated to the main users of the area —mostly students— such as study rooms, internet cafes... However, the area has the potential to be transformed into a kind of 24/7 multi-functional welcoming place, where even to stay, if working properly with accessibility, safety, attractiveness and innovation. It is the main entrance gate to the city, very close to the historic centre, the new residential area of Quartiere Novello and the new campus of the University of Bologna in Cesena. Elena Giovannini, from the Municipality of Cesena, was talking about this intervention at the URBACT Festival. She highlighted three key messages:

- Working closely with the local community, and the importance of involving stakeholders and citizens in small-scale actions with an experimental aim. In the KAIRÓS framework, they have particularly involved high school and faculty students in a flash mob called “desire wall”. They have also engaged the school of architecture to conceptualise and develop some tactical urbanism actions as pilots and tests for the future. As Elena told, they in Cesena have learned from their own failures, when retrofitting the Old Market building, at the city heart, without taking into account citizens’ view and willingness, with the result that the community is barely using it.

- Multi-level funding orchestration. Due to local government´s poor financial capacity, which is a serious obstacle for sound strategies on heritage-driven urban regeneration, small and medium-sized cities should address multi-level governance in terms of fundraising. In particular, targeting national and regional funding sources related to housing, urban regeneration, cultural heritage, climate change and energy transition. In this respect, Cesena has already secured 10 M€ from the Italian Recovery and Resilience Plan, which is funded by NextGenerationEU, to build up a new bus terminal and refurbish the former site as a new public square. They have also got regional funds to retrofit part of the old Arrigoni factory building as venue for the CesenaLab incubator and the regional employment services.

- Reconciling hard and soft planning. Finally, it is worth noting that Cesena has skilfully got the point on how the action plan driven by the URBACT method complements and enhance the existing local planning framework with regard to urban regeneration. So, the former works as a type of “soft” planning, complementing and supporting the “hard” planning figures underway —e.g. general urban plan, mobility plan— and the main projects with a tractor or physical transformation capacity.

Miguel Rivas

Partner at TASO and lead expert for the KAIRÓS Network. KAIRÓS is an URBACT Action Planning Network on heritage as a driver for urban regeneration, joined by Mula (ES) Sibenik (HR) Ukmergé (LT) Cesena (IT) Heraklion (EL) Belene (BG) and Malbork (PL).

With acknowledgments to Monika Sassin, Marta Borowiec, Małgorzata Majchrzak, Radomir Matczak, Elena Giovannini, Luisa Arrigoni and Anna Uttaro.

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on