Social Impacts of Infrastructure Reconnection Initiatives: Focus on Displacement Risks - by Brian Rosa

Edited on

27 July 2022As Ad Hoc Expert for RiConnect, along with evaluating individual projects and the overall framework of the project, I have emphasized the need to tackle concerns around residential and commercial displacement that are often driven by projects aiming to reconnect spaces historically dominated by large-scale, above-ground transportation infrastructure, or in the reconfiguration of transport infrastructure more broadly. This has arisen from my previous research on the role of railway infrastructure in shaping urban spaces in the United Kingdom and United States, as well as emerging studies of “green gentrification” in North American and European cities, particularly the work of the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

We must expect that actions associated with RiConnect will have socio-economic reverberations at a variety of metropolitan scales. Undoubtedly many of these projects will offer clear benefits to a broad cross-section of society through improving metropolitan mobility, improving public health, and addressing climate change. The impacts of infrastructural reconfiguration projects can be evaluated from a variety of perspectives. In urban design, increased pedestrian permeability plays a key role in the socio-spatial impacts of infrastructural transformation. At the metropolitan scale, shifts in public transport and active mobility infrastructure have impacts on movement patterns, density and shifts in land value, access to public space, and many other interlapping themes of relevance to metropolitan planners. A less comfortable discussion is how these projects may—deliberately in inadvertently—drive displacement as part of a process of land revalorization.

Planners should take seriously concerns about green gentrification: a process in which environmental improvements increase housing prices and attract wealthier new residents—and businesses to serve them—in historically marginalized communities. It is increasingly acknowledged that low-income areas on the periphery of city centers, often sharing space with industrial activities, have historically been prioritized for large-scale infrastructure projects requiring widespread demolition, and have left physical connections severed. This dynamic was observed with railways in the 19th century and with highways in the 20th century. The negative impacts of above-ground infrastructures—poor air quality, noise, vibrations, darkness—have typically led to districts surrounding them remaining physically and socially isolated, segregated, and stigmatized. Many communities have been sidelined, and remained low-income, precisely because of the dominating presence of mobility infrastructures. In overcoming these barriers, a key concern is whether, and how, preexisting communities can benefit from these transformations. Thus, the main concern associated with green gentrification is displacement. The impacts of reconnection projects—and the way public authorities anticipate and respond to them—depend on a variety of factors related to real estate pressure, tenant protections, the amount of public housing, local governments’ abilities to shape economic and social policy, and political willingness to foreground the protection of the socially vulnerable in the face of urban change.

Understanding displacement risks is an important step in assessing the social equity issues around planning initiatives—even if those initiatives are conceived as being for the benefit of all—and to do so requires the collaboration between public bodies and community organizations to anticipate risks through the interpretation of demographic data, forecasting, and proactive public policy. This is especially important in the face of “greenwashing,” in which sustainability actions and discourses are used to push through what would otherwise be controversial projects, or to underplay potential negative social impacts associated with them.

Better accessibility, improved public space, or cleaner and more active mobility can help improve economic, social, and health conditions at the local level. However, with physical improvements to districts that have historically been neglected often comes increasing interest from investors to capitalize on newfound centrality, improved image, and new public spaces and facilities. Under such conditions, residents and businesses who have traditionally dwelled in these locations often find themselves under displacement pressure. This pressure is especially acute for residents and businesses who rent rather than own their properties. Furthermore, since the spaces along and beneath large-scale infrastructures have often sheltered the unhoused, inhabitants under displacement risk are often undercounted.

The challenge with the improvement of mobility infrastructures and the creation of public spaces is that the people who have experienced environmental degradation may be displaced, unjustly excluded from the improvement of their everyday surroundings. The displacement phenomena associated with green gentrification, “the high line effect”, and gentrification associated with transport-oriented development (TOD), have been well documented in recent years.

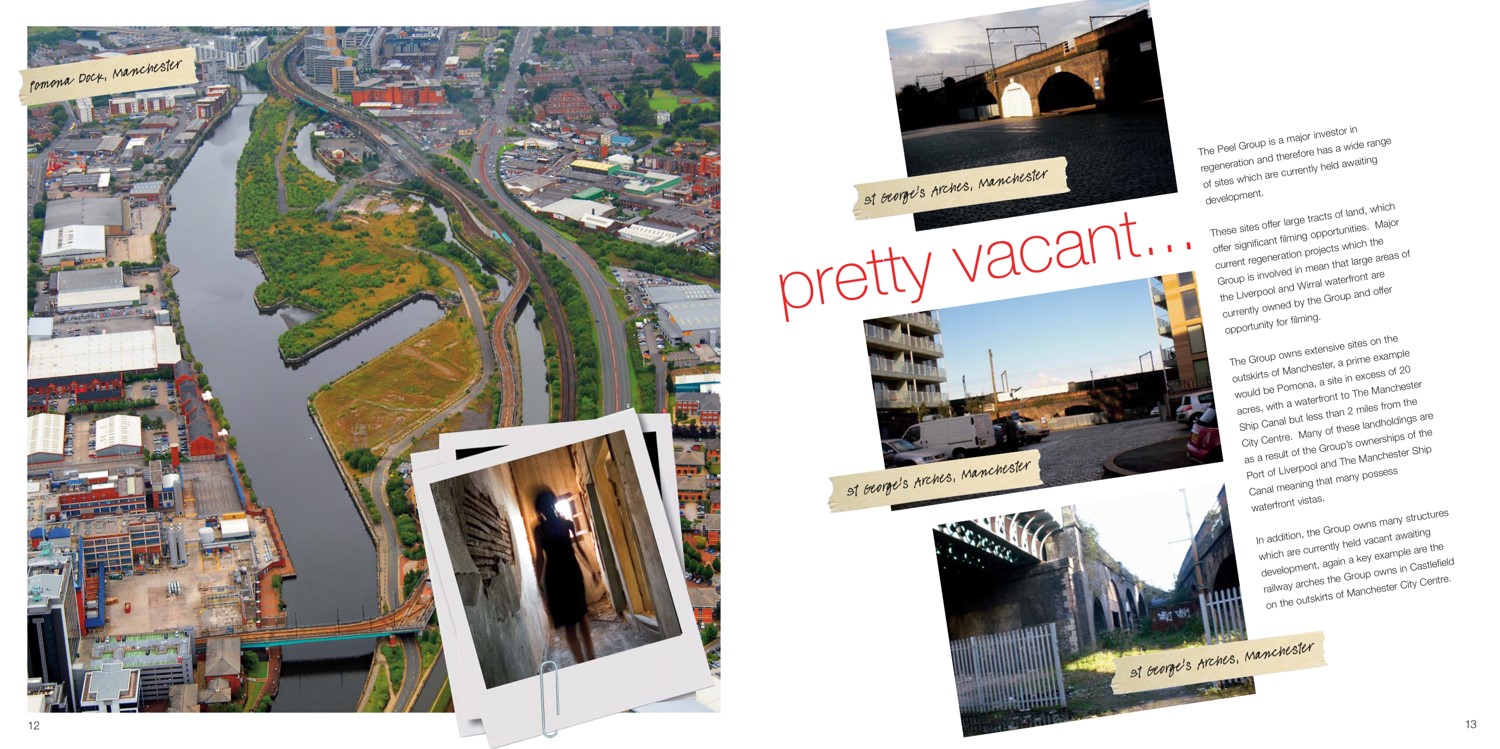

Formerly industrial areas awaiting for development, as offered in a real estate brochure. Source: The Little Book of Great Locations, Peel Holdings, 2011.

Of course, as a multi-faceted policy concern, displacement is not an issue that can be solved uniquely by planning or urban design, though we must also acknowledge the uneven social impacts of introducing new amenities and improved environments. Therefore, we must think about how concerns of displacement can be proactively addressed as part of the project of transforming mobility infrastructures from the beginning of a project’s conceptualization. How this is done, even more so than other elements of planning policy, is dependent upon local and national laws and policies.

While there is no one-size-fits-all method to evaluate displacement risk, one needs to consider whether there is an anticipated influx in real estate investment, what sort of public incentives and requirements there are for private developers operating near a new project, whether capital construction costs are available for the construction of new affordable housing, whether there are anti-displacement measures in place for pre-existing residents and businesses, and the monitoring of changes in socio-economic characteristics (household income, ethnicity/race, median rent, etc.) in an areas nearby planning interventions in relation to overall changes in a city and/or metropolitan area over time. At the level of policy, this may also take into consideration how public bodies address land value capture in their planning permissions to ensure that local communities can recover and re-invest land value increases driven by public investment (land value capture).

To take displacement risk seriously, evaluation and assessment must begin from the conceptualization of a planning initiative and then impacts should be tracked over time. For example, have new improvements and amenities had a measurable impact on surrounding property values, as compared to the city/metropolitan area as a whole? If so, what measures are in place to protect private market renters from displacement through rent rises?

The underlying assumption of anticipating and monitoring concerns about displacement is that, to the greatest degree possible, the environmental and mobility improvements provided by such spatial reconfigurations should prioritize the benefits of pre-existing occupants as well as anticipated newcomers, minimizing displacement.

Creating a Framework for Displacement Impact Assessment

Below is a table of different forms of displacement to consider how different projects may directly, or indirectly, relate to them. Not all drivers of displacement are directly related to gentrification, but most are relevant to both residential and commercial land use. Some of these categories of displacement are the result of processes and relationships that occur independently of public intervention and regulation, but most relate to public policies around social equity (or lack thereof), which themselves will vary in different geographical contexts.

Categories of Displacement

| Forced | Responsive |

Direct displacement |

|

|

Indirect/economic displacement |

|

|

Exclusionary displacement |

|

|

Table modified from Zuk et. al. (2018)

European cities can take a cue from the emergence of Displacement Risk Assessments in cities of the United States. In the face of housing crises, municipal governments have begun independently developing tools as elements of equitable housing policies, relying largely upon demographic data. In a variety of US cities, it is increasingly acknowledged that issues of historical racism also underline the targeting of particular neighborhoods for redevelopment. New York City has recently passed legislation calling for the creation of a citywide equitable development data tool, a citywide displacement risk index, and racial equity reports for major land use actions as a first step to address land use approval and environmental review processes, led by the city’s Public Advocate Office in collaboration with planning and housing departments. Typically, residential displacement risk is measured by changing private residential sale and rental markets over time in relation to the inflation-adjusted median income of an area. The ratio tests whether a typical household living there before a major transformation could afford to buy/rent in the same area upon its completion.

Of course, the data available, the ability to collect them, and measurements of different indicators (poverty, etc.) vary in different geographical contexts (country, region, etc.), meaning that there is not one catch-all approach. Neither have such assessments typically focused specifically on the impacts of infrastructural reuse and reconfiguration projects. Nevertheless,

There are a number of common considerations that can be applied to a broad variety of contexts. The idea is that, with access to appropriate data, the socio-economic impacts of a redevelopment project or planning intervention can be forecasted, allowing for policy safeguards to be put in place to minimize displacement and other adverse social impacts.

To do a robust analysis of the impacts of planning initiatives requires coordination with other agencies, as well as civil society organizations, to gather and assess social characteristics of an area impacted by a new development, and to project how the benefits and risks of this planning intervention will impact surrounding communities. This, in turn, may impact whether, and how, a project goes forward. Based on an assessment and anticipation of a project’s impact, it then requires linked-up thinking, coordinating with different public bodies and civil society organizations, to create (or enforce policies) put in place to safeguard households, businesses, and communities. These policies would establish various mechanisms to minimize the displacement of residents and businesses so they may benefit from the environmental improvements occurring in their surrounding areas.

Brian Rosa is urban geographer and photographer, and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Department of Humanities, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. He is an Ad-hoc expert at RiConnect, where he supports the research of case studies and the social impact of infrastructure projects.

Brian Rosa is urban geographer and photographer, and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Department of Humanities, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. He is an Ad-hoc expert at RiConnect, where he supports the research of case studies and the social impact of infrastructure projects.

Cover image: Rambla de Sants, promenade above covered train tracks. Source: Brian Rosa.

Submitted by Mikel Berra-Sandín on

Submitted by Mikel Berra-Sandín on