Transfer Story: Replicating the mediator’s role from Lodz to Birmingham - what happens if we empower community representatives to become mediators?

Edited on

30 March 2021The last decade saw Birmingham fall victim of the most drastic austerity measures applied by the national Government after the financial crisis in 2008. The change of the national political leadership left Labour-led local authority exposed to the most severe budget cuts. Immediately after the economic crisis of 2008, Birmingham City Council was faced with unrealistic saving targets and several difficult decisions had to be made.

Over 50% of workforce had been made redundant and several key functions were lost. BCC’s Regeneration Team was one of the first to be disbanded and in 2010 the regeneration function stopped existing altogether. From that year onwards, regeneration projects became purely driven by housing (with minor exceptions). More, a new term was coined, ‘housing renewal’ that stripped capital investment of any social interventions.

It is worth to explain here that Birmingham is one of the youngest cities in the UK and has a growing population which means our housing needs are growing quickly. By 2032 we need to have new 80,000 houses built. So, over the recent years, the biggest political focus has been placed on inward investment and quantity took precedent over quality of projects.

The first attempt at different approach came in 2017 with the UIA funded USE-IT project that enabled a new innovative partnership to be formed with the intention to add human centred interventions to a housing Master Plan. This partnership laid the foundation for the REMIX project.

Learning from Lodz on their regeneration approaches opened a great opportunity but also constituted an immense challenge. Despite visible similarities between Lodz and Birmingham, the situation in both cities and management processes that sit behind large regeneration schemes are fundamentally different. Lodz is utilising their largest structural funds allocation yet and their problems are centred around spending the money on time and spending it well. Birmingham struggles with any money for social projects as regeneration is driven by private developers - so there is very little space for social experimentation and risk taking which are the foundations of the REMIX best practice.

What made Lodz a leader for us then? Lodz offered an example of an incredibly efficient internal reorganisation – and demonstrated how to effectively implement changes in the city management model. Observing this change happening in Lodz, gave us several ideas we could adjust and adapt to Birmingham conditions.

First, was the role of mediator in the regeneration process that Lodz developed over the course of the project. Fascinatingly, its first iteration raised more questions than answers but, with time, as we got to understand the process better, we realised that it actually was very transferable. We took the concept further; however, and placed the mediators in the community as opposed to in the city administration. The reason for this alternation was simple. Birmingham City Council workforce has been so vulnerable and transient with Planning staff changing frequently. Community, for a change, was there to stay. Some of the community representatives have lived in the area for 30 years and are the real ambassadors. This makes it much more sustainable and not vulnerable to funding cuts or management decisions. The hardest part of this modified approach is trust building at the beginning of the project. There is a lot of learning required for somebody from the community to be able confidently explain regeneration processes in the community. However, once he or she is trained they remain in the community and act as permanent ambassadors who translate often difficult challenges the City Council grapples with to the community.

What were the results at the local level after adapting the practice in Birmingham? First of all, we managed to rebuild trust in the community and stopped them from opposing every plan coming from Birmingham City Council instead opening space for collaboration and co-design.

We also introduced an additional mechanism, Community Economic Development Planning that strengthened the capacity of our mediator, Sam Ewell. It allowed him to mobilise people around him and build a momentum for change. Sam is also the ULG Coordinator, which gave him a very powerful mechanism to build a group of stakeholders around him.

Within CED Planning three important attributes are emphasised:

1. The overall focus is the economy. CED is all about re-shaping the underlying economic system in a place, rather than working on improving people’s capacity to live well within the existing environment.

2. The economy is a means to an end, not an end in itself. Rather than emphasizing economic growth as the end goal of local economic development, a CED approach is interested in economic development which generates human wellbeing within environmental limits, at a community level.

3. It’s led by the community. In CED, the power to drive the change rests within the community of residents, local businesses, local service providers including councils, community groups and voluntary sector organisations with a direct stake in the economic health of that area.

The Summerfield CEDP initially focused on bringing a local playing field located by the Edgbaston Reservoir back into community use; however, it evolved into a mechanism to bring the community and City Council together to explore the future of the whole Reservoir. Rather than residents campaigning against redevelopment plans that they felt did not meet their needs, they instead used the CEDP process to create an alternative. This ultimately led to better partnership working with the City Council and enabled the residents to essentially co-produce the regeneration plans. As a result, an alternative Community-Led Master Plan for the Reservoir was created.

The same activities resulted in several large local events and other initiatives like the creation of two cooperatives: Eat+Make+Play and Warm Earth that strengthened civic capacity locally and increased local economic resilience.

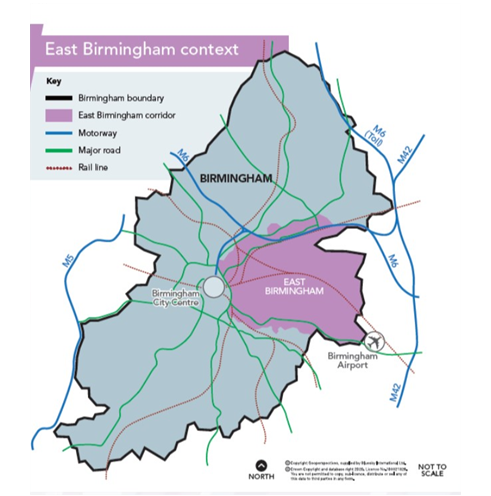

The lessons from the Reservoir, encouraged Birmingham City Council to explore community leadership. Simultaneously, BCC decided to fully embrace the principles of inclusive growth. In 2019, we started working on a new economic development strategy for East Birmingham and made sure that the it becomes the demonstrator of inclusive growth for the city and the region. I was offered a yearly contract with the Planning team in August 2020 to transfer best practice from the Edgbaston Reservoir to East Birmingham. In that same month, we started forming a delivery unit for the East Birmingham Inclusive Growth Strategy and the structure of this has been modeled on the Lodz Regeneration Team. It is a multi-disciplinary team and aims to link several BCC departments with the city-region administration (West Midlands Combined Authority) – its remit is to support the regeneration of the area and foster inclusive economic development. The main purpose is to involve communities and include them in the redesign process of their neighbourhoods to make sure that the benefits of the development are felt where they are needed the most.

The main benefits of this policy at the local level are not yet fully visible but the biggest difference is already seen in the overall approach to community engagement. The larger scheme has not changed, the use of funding has not improved; however, resident engagement has improved significantly.

Lodz team has been extremely helpful in explaining both the benefits and difficulties of their approach. The openness resulted in much deeper understanding of the foundations that need to be laid for the best practice to be introduced.

Another important aspect of the exchange were skills – both cities discussed at length the necessary recruitment and training of city employees to be able to function as a part of the new system. Birmingham’s decision to introduce the new cross-sectoral model of working in the East results in some intense work on skills audit and mapping individuals across the organisation that could join the team. Training is organic at this stage but has already resulted in greater risk taking and openness for innovation which was earlier not possible.

Both Lodz and Birmingham learned about the importance of risk taking in regeneration. One of the frequently missed learning is that innovative solutions require leaders who are not afraid to take risks. In the case of Lodz, that role is fulfilled by Ewa, who leads the team of mediators and pioneers solutions across the city.

The example of multi-generational housing from Lodz demonstrated for us that, for the residents, it doesn’t matter which city department deals with their issue as long as they are being listened to and in effect have somewhere to live. All relevant city services need to come together to create a systemic change. In Lodz, not only we have seen a model of successful mediation but also an example of successful implementation of pro-active decisions to create improved living conditions for them, like the multigenerational housing.

This doesn’t happen in Birmingham easily. Our services have been disjointed and weakened for much too long to be able to recreate the best practice fully. We could not make an identical copy of the best practice, but we have taken the essence of it and adapted what was needed for our local circumstances.

In summary, Birmingham benefited from the project in multiple ways. The project gave us an opportunity to try an innovative and risky solution of placing the role of mediator observed in Lodz in the middle of the regenerated area and to train members of the general public to fulfill that role, which was a transfer of best practice and a modification to fit the concept to the local conditions. In our approach, aiming at greater empowerment of the community, it was only right to place the ULG in the hands of the community as well. It was a difficult decision and required a great deal of trust placed in the community. This in itself has been a very powerful change and led to some event greater changes. The momentum created by the ULG continues and will easily outlive the Transfer Network funding because all the local stakeholders see the value of working together and want to carry on working together and strengthening their capacity.

In addition to that, the project put a great deal of pressure on the local authority’s Housing and Planning teams to alter their approaches and involve communities in the co-creation of the local master plan. This is seen as a wider work on culture and policy change and it is still on-going; however, REMIX created a very powerful example of implementation which will be replicated elsewhere within the city (East Birmingham).

Finally, through applying the integrated management model observed in Lodz, Birmingham City Council introduced similar solutions – setting up the Rapid Policy Unit for East Birmingham combining three local authority and creating a powerful body that would work on the regeneration of East Birmingham breaking silo working between directorates and service areas.

Submitted by n.rydlewska on