'Migrant crisis': which engagement for Europe and the Urban Agenda?

Edited on

12 January 2018Laura Colini has written an article on the 'migrant crisis': which engagement for Europe and the Urban Agenda, based on a European Perspective, here our own Mark Boyle gives his response to this article, but from an Irish Perspective.

Crisis or Asset-Base: An Irish Perspective – by Prof. Mark Boyle, URBACT Contact Point Ireland

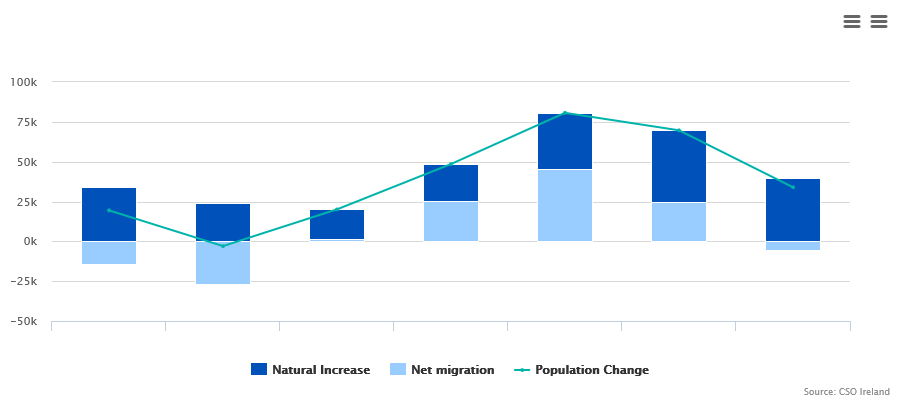

Whilst the Republic of Ireland has a long history of emigration, less well known is its history as a destination for immigrants. And yet during the period of the Celtic Tiger (1993 to 2007) the Republic of Ireland (heretofore referred to as ‘Ireland’) became a net importer of people. A significant minority of those who moved to Ireland in this period were Irish nationals (and their siblings) who were returning “home” after dwelling overseas for a number of years, in some cases decades. But many foreign nationals also came to Ireland not least from the new EU accession countries. Moreover, in the early 2000s, Ireland had historically unprecedented numbers of applications for asylum. The result: today, Ireland has a rich immigrant community and is home to migrants who hail from over 200 countries around the world. But of course the global economic crisis from 2007 has further complicated this picture. Emigration of Irish nationals from Ireland has once more returned as a significant demographic phenomenon (see Figure 1 below). Moreover, a proportion of recent immigrants, especially from the EU accession countries, have returned to their source countries or moved from Ireland to an alternative third country. Growth in migrant numbers has levelled off and net emigration has returned. At the same time, the number of applications for asylum has dropped dramatically.

Figure 1: Components of Population Change in Ireland

According to the 2016 Census, nearly 800,000 people or 17 per cent of usual residents were born outside the jurisdiction – mainly from the UK, Eastern Europe. Western Europe, and Asia. At under 10,000 Ireland’s total refugee population comprises less than 0.01% of the country’s population. Not surprisingly asylum applicants are drawn from a wider geographical base than the rest of the foreign born population, the most frequent countries of origin being China, Nigeria, Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Somalia.

Whilst it is debateable whether the notion of the ethnic neighbourhoods, enclaves, clusters and ghettoes can be applied to migrant and ethnic groups residing in Ireland, it is the case that most groupings show evidence of clustering and concentration. It is here that cities become important. Galway City has the highest proportion of residents born elsewhere (25% of all residents), followed by Fingal, Donegal, Dublin City and Monaghan (all >20% of the total population). Meanwhile some counties (especially Kilkenny, Offaly, Limerick, Waterford and North Tipperary) house comparatively low levels of migrant populations. With respect to residents born in the Rest of UK, interestingly peripheral, holiday and rural locations are preferred - counties such as Mayo, Leitrim, Donegal, North Down and Roscommon. In contrast, populations residing outside of Ireland/UK tend to record their highest rates in the main cities and urban areas (Galway City, Fingal and Dublin City (>16% foreign born). Meanwhile Polish migrants concentrate in urban centres across Ireland and display distinctive spatial patterns inside the main cities. Those with Black ethnicity show evidence of concentrating in Fingal, Galway City, South Dublin and Louth. Moreover, the Black population displays a very clear spatial distribution in Dublin City, dwelling in a number of specific peripheral locations. Asian migrants also chose to live in the principal urban locations (Dublin, Galway) and for the most part cluster into central locations in these cities.

The impact of migration has generated significant topical discussion. But alas a balanced debate on the merits and demerits of immigration has proven difficult. Appropriate discussions on the need for managed migration have at times given way to a post crash austerity fuelled politics which has, at its worst moments, pandered to racist and xenophobic attitudes and more recently to forms of Islamophobia. And so it is no surprise that many countries are trying to stop migration at its source, tightening their immigration and asylum rules, and toughening their border controls. It is necessary to cut through at times misinformed public opinion and to establish a debate on managed migration which is grounded in fact. It is clear that migrants can contribute most to host societies when they become integrated into the fabric of those societies.

Cities will incorporate migrants best when they respond to four key issues. Social integration occurs when migrants forge new social networks in the host society and secure equal access to housing, educational, health, and recreation facilities. Economic integration occurs when migrants plant new roots in the host society and secure employment. Through upward socioeconomic mobility they begin to achieve parity with the socioeconomic profile of the host population. Political integration occurs when migrants gain full citizenship rights in destination countries and participate as equal members in the political life of the nation (vote in elections, stand for elections, participate in public debate, and so on). Finally, cultural integration occurs when migrants are permitted to celebrate their own cultures, traditions, and customs whilst coming to appreciate the cultural practices of the local population and local ways of life (clothing, dance, religion, food, national belonging, etc.).

Whether cities in Ireland will develop into more or less hospitable places for immigrants to live and work remains to be seen. But it presents a crucial policy challenge for urban policy-makers.

Read Laura Colini's original article here;

http://urbact.eu/migrant-crisis-which-engagement-europe-and-urban-agenda

Submitted by Caroline Creamer on