Making heritage work for sustainable urban development - by Lead Expert Miguel Rivas

Edited on

13 June 2022The way the heritage field has evolved over the past years, with new concepts like heritage valorisation, urban heritage or historic urban landscape, is giving cultural heritage, in particular built heritage, a great opportunity to work massively as a driver for sustainable urban development. To make this happen —that is, to make the idea of heritage-driven urban development and regeneration work— we need to build up and mainstream a dedicated integrated approach.

Finding out the right integrated approach

The management of heritage sites, heritage cities and historic quarters is still largely addressed from two poles mainly. Cultural policy, with an emphasis on conservation, on the one side; and urban planning, mostly biased to land-use and regulation, on the other side. Not to mention the key role assigned to these spaces in relation to the visitor economy sector. Nonetheless, there is a growing interest from cities, whatever their size, in developing a more balanced approach to maximize the role of heritage in their strategies on sustainable urban development.

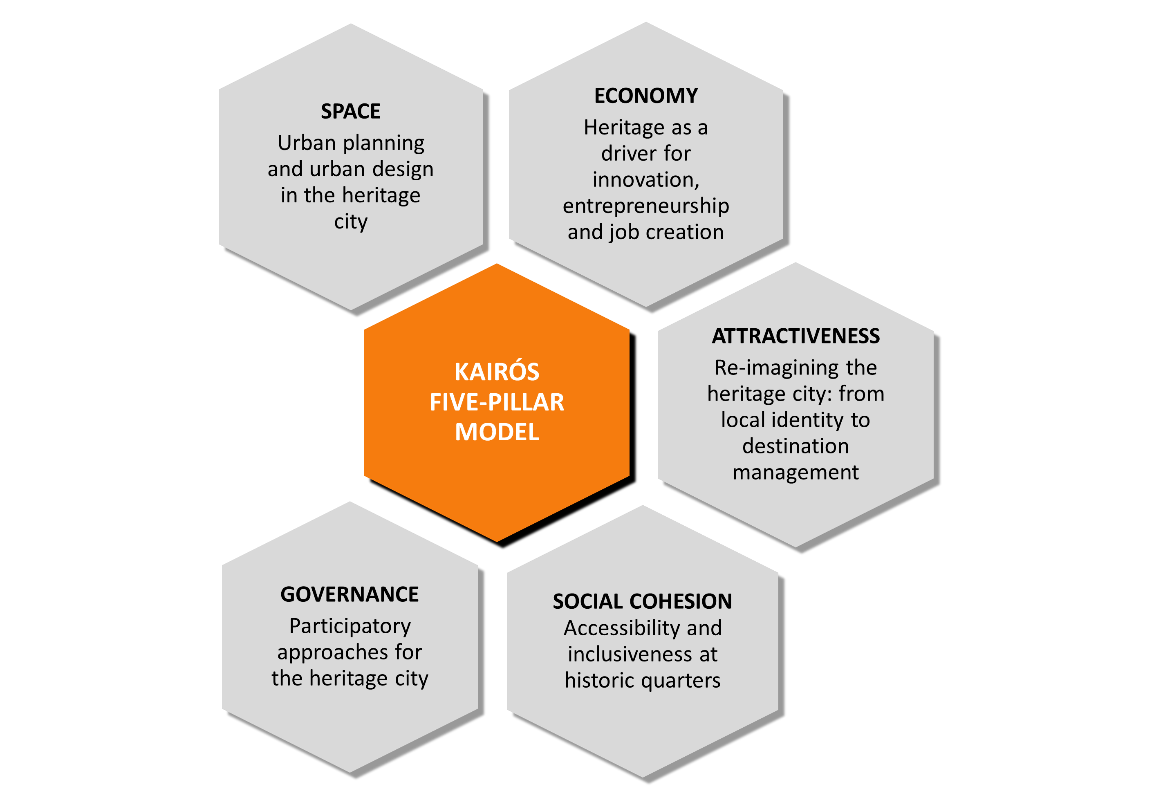

To meet this challenge, within the framework of the URBACT Programme, the cities joining the KAIRÓS network —Mula (ES), Šibenik (HR), Ukmerg (LT), Cesena (IT), Heraklion (EL), Belene (BG) and Malbork (PL)— have been testing a specific integrated approach by assembling five key dimensions, namely: Urban Space [all related to urban planning, urban design and the catalogue of carbon-neutral and smart urban solutions], Economy, Social Cohesion, Attractiveness and Governance. To make this model work properly the key question is how a broader conception of heritage valorisation can contribute to each of these pillars.

This integrated approach, which we have called the KAIRÓS five-pillar model, has proved to be workable to a variety of different local circumstances and needs. From revitalizing Šibenik's old town, a place with an outstanding beauty in the Croatian seashore, but affected by depopulation, tourism-driven gentrification and lack of urban vitality during the low season, to reverting the vicious circle of degradation of the historic Barrios Altos of Mula, in Southern Spain.

The work done so far, has given the opportunity to extract a number of insights that, perhaps, can be helpful to any city with the idea to expand the role of its built heritage as a driver to build the future. Let us highlight below some of them.

Harmonic layering or the right to make the city

To re-connect with the contemporary, the heritage city has the right to make the city, if needed. Both preservation/valorisation of built heritage and the production of new urban space may mutually reinforce —others can refer to this as harmonic layering. Thus, regenerating the historic Barrios Altos of Mula or the Holy Trinity quarter (Aghia Triada) in Heraklion, both with a badly degraded housing stock, does not entail preserving everything at any cost. Neighbourhood's new needs in terms of accessibility or public space may demand specific changes over the inherited fabric.

However, this idea is not always well received. In this regard, a vivid discussion took place ten years ago in my home city, because of the construction of the first skyscraper in Sevilla, a city with 700,000 inhabitants serving a 1.5 million metropolitan area. Despite the location was outside the buffer zone of the monumental area protected as World Heritage Site and even out of the historic urban fabric, ICOMOS made a strong opposition with the argument that the project would impact the visual perception of the monumental area. The delisting of Liverpool [Maritime Mercantile City] as World Heritage Site last year could also feed an interesting discussion in this regard.

This issue could be posed as the need for better methodological frameworks to make preservation goals more compatible with the contemporary city or, in Dennis Rodwell's words, “today’s overarching global priorities” (Rodwell, D. (2018) The Historic Urban Landscape and the Geography of Urban Heritage, The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice, 9:3-4, 180-206). In this attempt, UN-Habitat and the New Urban Agenda can show a path, rather than UNESCO only.

This is about keeping the historic city liveable

A main finding from KAIRÓS and other large-scale projects I have been participating is that promoting a better social access to cultural heritage has the effect of expanding the portfolio of heritage valorisation projects in the city, and that is key to develop a city perspective to heritage. Furthermore, this social-oriented approach leads to give housing a primary role in heritage-driven urban regeneration. In this issue, we need bolder schemes to retain the residential use in our historic quarters and face Airbnb-driven gentrification if the case.

For instance, the Portuguese city of Porto is delivering a disruptive housing policy specific for the historic centre aimed at stopping depopulation and the degradation of the housing stock in the area. The programme is called “Porto com Sentido” and runs as follows. On one side, the local public agency Porto Vivo engages homeowners with tax exemptions, paying rents close to the market value, anticipating these rents up to 2 years, and ensuring full maintenance during the whole contract period of 5 years. On the other side, Porto Vivo sublets those properties [in good conditions and excellent locations] at affordable rents, with values at least 20% below the market prices.

Besides Porto, another valuable contributor to the discussion promoted through the KAIRÓS thematic workshops has been Regensburg, in Bavaria. Monika Göttler, from the City of Regensburg World Heritage coordination team, understands that the primary goal for them is simply to make the urban heritage site a more liveable space. And, interestingly, for her liveability means “spaces where people like not only to stroll, go shopping or spending time in vacations, but also places where young families can find an apartment and make a living”. Today, in Regensburg, about 40% of new housing developments in areas within the buffer zone of the World Heritage Site must be devoted to subsidized apartments for low and middle-income families, as Monika reported.

Small-scale actions as an affordable way to do impactful things

It is about the value of experimenting. This has been a main lesson from Bologna, which is likely one of the most unprejudiced cities in giving heritage a new wider social accessibility. One of the stops of the KAIRÓS journey was a study visit to Bologna. There we learned the benefits of using Urban Living Labs as formula to craft out-of-the-box initiatives that ultimately are changing the way both the Municipality and the people address and experience cultural heritage or the historic centres and quarters. In this context, a number of tactical urbanism type of interventions were deployed in the area around via Zamboni, with the aim to get some historic squares free of the massive car occupation. The direction provided by the University of Bologna, along with the active involvement of selected local stakeholders and the funding support from the EU (Horizon Europe programme) were key for this successful experience.

In this respect, small-scale actions are an affordable way to start boosting liveability in the heritage city. For instance, coming back to Regensburg, last year they installed the so-called “deggi-deck” in the streets of the old town. It is a mobile, green summer deck containing power supply and wifi, and Ipads were available in a nearby coffee/cultural centre to be lent for free. The message is that cities and their funders and supporting administrations should acknowledge more extensively the value of these pop-up and tactical urbanism types of interventions, proofs of concepts, awareness-raising small events, challenge-based calls… to break inertias, change mindsets and test new ways of doing with regard to heritage valorisation.

Inter-generational dialogue helpful to foster liveability in the historic city

Some KAIRÓS cities, such as Šibenik or Malbork, have showed us that promoting inter-generational dialogue is not a minor but a primary tool in old town regeneration, in order to foster liveability in the historic city, which is often turning into an ageing city due to depopulation. Moreover, it is a vehicle for transferring identity values and sense of place to young people. For instance, in the Word Heritage city of Gyeongju, in the Republic of Korea, elderly women are untrusted as storytellers in kindergartens and can earn some money with it. It is a way of supporting a vulnerable group while making intangible heritage work to seed sense of place and local identity. Indeed, more authentic heritage valorisation needs to be cultivated from education and awareness. The impact of this line of work is more long-term, and that is why it is not always much appreciated.

Are you already on it?

The KAIRÓS journey entails an invitation to other cities, in particular small and medium-sized cities, to re-examine the potential of its built cultural heritage as a driver for the city development. Addressing heritage valorisation [in all its dimensions] as a policy concept is a first step, to then building up an integrated approach, duly adapted to the specific local circumstances and challenges. To ignite the process, why not start with the following questions?

Are we working with a sound and explicit integrated approach for the heritage city, whatever the target area? If so, what room for improvement?

What does the idea of heritage-driven urban development suggest to us?

Any specific approach or idea to promote affordable housing and keep the residential use in our historic quarters?

Miguel Rivas

Partner at Grupo TASO and URBACT Lead Expert for the KAIRÓS Network

The author expresses his gratitude to the Organisation of World Heritage Cities for his involvement in the discussion with OWHC cities for the preparation of the 16th OWHC World Congress.

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on