Laituri - An urban laboratory to make strategies alive

Edited on

02 October 2018“Helsinki wants to become a city that creates a platform for activists to act.”

Interview with Reetta Heiskanen

5 June 2016

Laituri is an urban information centre in Helsinki established in 2008. Attached to the Helsinki Municipality’s city planning department, Laituri helps disseminating information about the city’s development plans and new projects through exhibitions and presentations. Instead of being a one-directional communication channel, Laituri also acts as an interface for feedbacks from citizens: with the help of workshops and discussions, the centre plays a key role in participation processes addressing urban transformation in the Finnish capital.

What was the reason of opening Laituri?

Laituri opened in 2008 and we benchmarked a couple of information centres in Holland, Rotterdam and Amsterdam and well as planning projects in big cities like Hamburg and other places in Germany. Laituri was established here when Helsinki’s cityscape underwent great changes. It was a transformation from the industrial era to the postmodern information age. There used to be a cargo harbour area right in the heart of town called West Harbour and there another harbour on the eastern shore of the peninsula, both of which areas were about to change function. Around 2008, when we opened, a lot of land became available for construction right next to the downtown and the historical centre of the Helsinki peninsula. These development projects were quite significant, we calculated that approximately 10% of the city would move to new areas. This is why we started working here in Laituri because we wanted to communicate with people and wanted them to participate in developing the environment, not only to tell them what is going to happen but involve them in the design and planning of their new neighbourhoods.

What is the rationale behind these transformations?

Helsinki is a maritime city, we have of 130 km of seashore and 300 islands, we are also a very green city. We have a central park that starts right in the heart of town and stretches all the way to Lapland. So these are the factors that the citizens of Helsinki love, their seashores and their green parks. Helsinki has 635,000 residents today so it is not a big metropolis but if we combine the neighbouring towns and smaller municipalities then we can talk about 1.2 million residents. And Helsinki happens to be one of the fastest growing cities in Europe, we are in the top ten. We receive approximately 9000 residents each year party due to the geography of Finland: it is a long-stretching country and because of the economic situation and high unemployment in Eastern and Northern Finland, people are suffering and especially the educated part of the population is moving South. We also have a growing number of immigrants and refugees like everyone else in Europe so nowadays we calculate that in 2050 we will have a quarter of a million more people living in Helsinki. That was the challenge of the new town plan which we had just finished working on last year.

|

How are these demographic changes reflected in the town plan?

Helsinki is an important land owner. If you look at the map of Helsinki, the city owns up to 65% of the land and when it comes to the old harbour areas, Helsinki is the only landowner. That means we have a monopoly on what is actually planned in these new areas and it also means that the city finances the work and they collect all the profits when they rent or sell the land to be developed.

In order to able to provide means of growth, we need to provide more apartments to the new residents. Helsinki signed a contract with the government of Finland that we must be able to provide up to 6000 new flats every year. And we work hand in hand with the neighbouring municipalities and the government of Finland provides financing for the public transportation. The goal in Helsinki is to expand our historical tram network that we have had for more than a hundred years, by building new bridges to connect the eastern suburbs more to the city centre and a new light rail system which will function East- and Westbound, because the rails that we have today only function North- and Southbound. Then of course we have a metro line that connects the Eastern suburbs of Helsinki and we will hopefully have a metro line this year that will connect the Southern suburbs of Espoo to the downtown. To summarise, Helsinki is changing fast and this is why the city of Helsinki has been developing digital methods in order to enable people to participate in the development.

How does citizen participation in city planning works in Helsinki?

Historically, all the plans were made by officers in the departments and they only gave a small chance to the public to participate. We changed the law in Finland in 2001; the new law said that all the neighbours and local people must have a chance to participate in planning. During the 2000s, we were working on how to make people participate. In Helsinki, whenever we have a plan initiative, we announce on our websites and information boards in the town hall, and we make announcements in the local newspapers that “now we are starting ideas on a new detailed plan and everybody can join us.” The problem is that we kept the process open for comments only for two to three weeks; now we came to realise that life is so hectic, that we cannot really expect people to participate in such a short period of time: we may need to change these procedures a little bit so that we can have longer periods for people to give their ideas. After this consultation, there is normally one or two years when the architects or planners work on the detailed plans and when the draft is prepared, it becomes official and goes through the city board and the council. Also when the politicians took their decision on it, the public has the right to complain. In the communication and the participation department we are trying to our best effort to not have many official complaints, because it has been calculated that every time we take our plans to the court, it costs about 1 million euros for the city. Then there are also delays so you can believe that the constructing business is not happy either if the construction does not start on time.

What is the focus of Laituri’s work?

In Laituri we combine methods of communication, participation as well as customer service. It is important because in most cities customer service and participation are not connected. When we talk about city planning, we still often go up to the ivory tower and look down at the city. When we talk about participation, it is not something you can study as such. So in the communications unit we have people who have degrees in communication, others in cultural and development studies; some people have their background in environment and economics, others in land use and more technical aspects. The only way to really connect with the grassroots is to look at the response that comes from people. This response does not necessarily come to communication officers; actually it goes more to those who work in customer services, because they receive not only complaints but also a lot of ideas.

How do these ideas arrive to the Municipality?

In Helsinki we have a web-based map solution where people can send their messages to the Municipality. The public work department receives up to 70,000 complaints a year. That may have to do with maintenance issues, and some of these complaints are really easy to handle as they are technical matters. But when it comes to city planning, we receive up to 4000-4500 complaints or ideas in a year from citizens and they are not always easy to answer.

|

Can you give an example?

Many people criticise the traffic solutions in Helsinki, they want to improve the parking system, change the programming of traffic lights or improve other matters that are actually not easy to solve. Because if you change something in the traffic, other parts will suffer. This is why Helsinki created a mobility strategy that focuses on pedestrians, after pedestrians come the bicycles, then public transportation, then in the fourth place private cars and after that transportation. The idea was that even though the city is kind of dense, we are trying to find a separate lane for each means of transportation so that everybody can have a smooth exchange. It means that when we receive a lot of interest from the public, we have to keep in mind our strategy that we want to promote pedestrian and bicycle traffic.

How many citizens follow and comment on the urban plans?

When we organise a participation process and open a web discussion or a forum, we receive about a hundred comments for a smaller project, and about a thousand comments for bigger projects. Of course, making the town plan for the whole city was exceptional, and we received 33,000 comments and 1400 official complaints: it has taken 10 months to process the complaints. The town planning process was like a new channel of participation. Many of the 33,000 answers had more than one points so we had up to 50,000 comments from people.

We also received good feedback about the influence of the comments: if we just collect data or information, if that does not transform into the plan, then our work is not well done. I would say that anytime we compare our work with different cities, people often feel that Helsinki succeeds quite well with the participation. We definitely do a lot more than the law requires: we were graded 8+ out of 10 by the citizens for the participation process related to the town plan. Helsinki makes hundred detailed plans a year and there are always people opposing every one of them, so we were quite happy that pretty much everybody found the atmosphere of participation fair. Even if people cannot change the work of the department, they still feel they receive fair treatment. And this of course is a big reward for us for our work in communication.

What is the role of online platforms and social media in participation?

Last year we were working on the new participation strategy. It became apparent that because of the information flow it has become overwhelming. People cannot even follow their own Facebook feed anymore due to so much info. That is why the Helsinki app is so important that people receive the information on their phone about what is happening right now. We also have a service that anybody who wants to follow town or city planning they can join our newsletters. We call it a plan guard. Anytime there is an initiative in Helsinki with a new detailed plan, they receive a message in their personal email so that they can participate. In the new participation strategy we really want to receive information from citizens about how they utilise the built environment and what their hopes are: we are creating many services that focus on the users.

Two years ago, we made a survey: when we asked people about what channels or medias of participation they prefer, 61% chose web-based participation and almost the same percentage preferred social media. We are going to make a new survey this autumn and I expect the percentages to swap, because our gut feeling is that social media is preferred now, and the websites are less interesting to the public today. We do not have a social media strategy as such. What we do is we do a multidiscipline work where we always combine social media with other methods. We have a team of 12 people and all them work with social media. Last year we created guiding principles for our planners to join the social media but it is not compulsory for them. Some planners do not want to use their name because they are afraid of the hate talk the would receive. So we have created planning department profiles and we mediate between the comments and the planners’ answers. Now that social media is growing, maybe now we need to have stronger recommendations. The younger generation is more eager to join: the city department hired a bicycle coordinator and her job is to be active on social media. We have no comprehensive strategy but step by step we are trying to find people with focus in this.

If anybody from the department notices that a discussion is rising we want our staff to come to the head of communication and ask what they should do about it or they can instantly act themselves. We do not tell them what they say or not to say, we trust our staff that they know their own business. So the ones who know it better can have a free say in every matter on social media. We try to follow it and react instantly. We try also to provide correct information, because some plans have been misunderstood or misinterpreted.

How does Helsinki experiment with new forms of participation?

We had already realised that the ways of participation and communication have actually reached a point of symbiosis. Nowadays I try to find synergy between the local people not only to have them participate within traditional methods but actually to create a system where we can co-produce and work together. I have to be honest: in Helsinki, people cannot make their own town plans yet. But we have come to a stage where they create their shadow plans. So a couple of years ago when our department was working on the town plan, some activists, local architects, researchers created their own shadow plan. And that is very interesting because then these two plans started to communicate with each other. The shadow plan was taken to the administration of town planning and we cannot know how much influence it had on the town plan but it was groundbreaking. Now when the Helsinki Municipality develops an area, there are often activist groups who create their own shadow plans and they start promoting an alternative vision. In the near future, perhaps we can expect that some official plans can be created through social media. In this process, we might have an architect who is interested in these tools, and actually co-produce something with the local community.

The activists who create shadow plans use a lot of effort, produce data and analyse the data, and create maps or detailed plans themselves. It has to be semi-professionally made to qualify as a shadow plan. Most activists groups – we call it the fourth sector – are professionals themselves. Although Helsinki is a big city I would say we have low standards of bureaucracy, everybody basically knows who the head of traffic planning is, for example, and we would take either the plan or we could invite the group of activists here to sit down with the responsible. We prefer face to face communication in these matters because then also the activists have a chance to explain further their ideas.

People in the municipality who work on participation methods say that anytime a shadow plan is created we should take it to the top planning administration and show it to the board of politicians as well. But others think it is maybe not such a good idea to make it public every time. Because sometimes the shadow plans are made too late and it is not worthwhile when we already have a draft plan to bring in an alternative plan because it is too late in the system to start working on it all over again. If we do two years of work and then somebody at the very end of the process decides to make new initiatives then it is too late. We have to encourage people to come and co-create in the ideas stage or the early stage of creation.

|

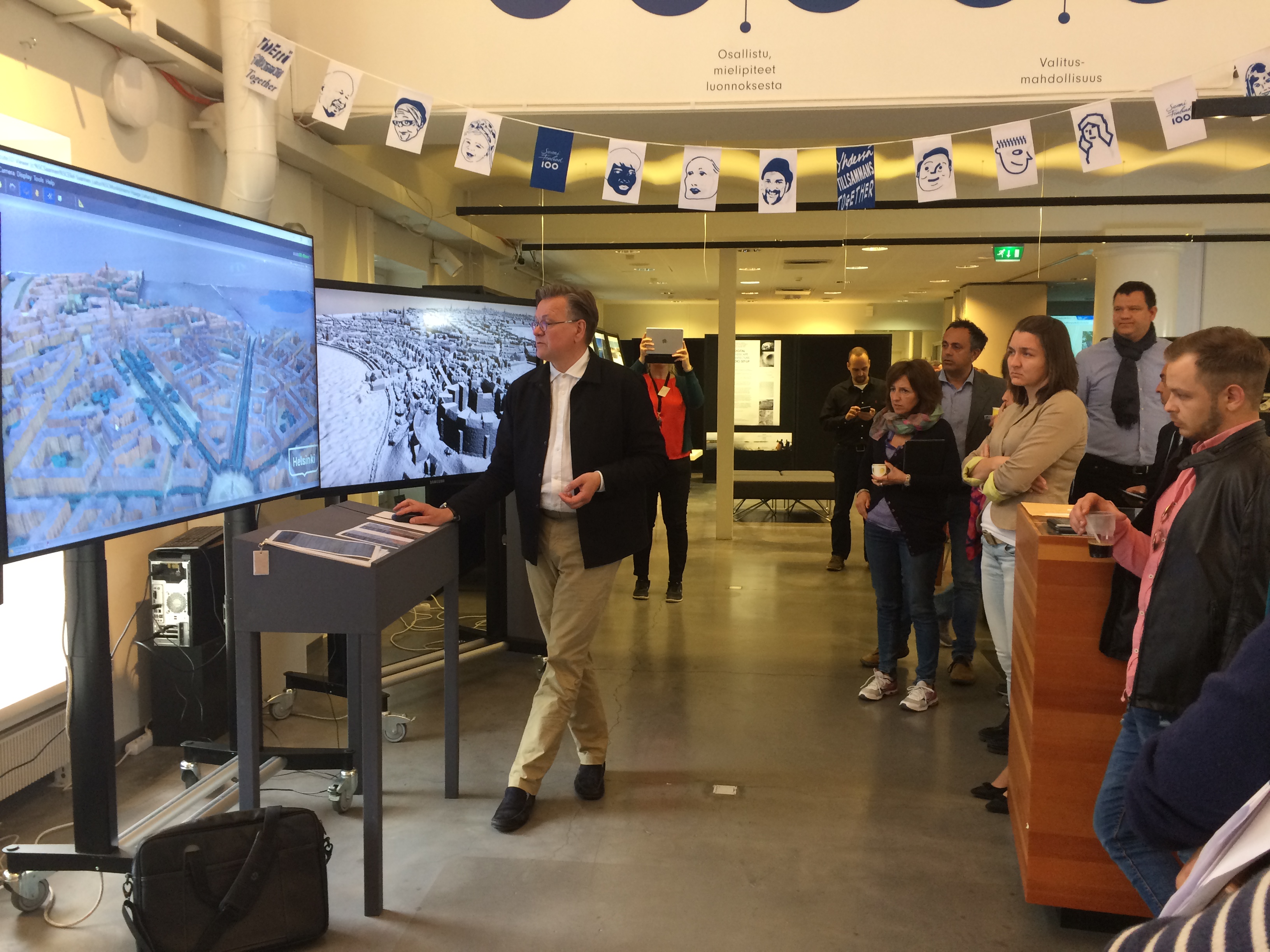

How does Laituri as a space contribute to these processes?

I wold say that this physical space has worked really well in terms of providing detailed information. When people wake up in the morning, they pick up the paper and read a story and their head is full of questions. They can ask questions on Facebook but there is not really anyone answering them. Although our planners are also active on social media it is not possible to answer each and every question. But people come here and we provide more maps and more data and often the problem is solved because they understand more of what is happening.

This place works as a mediator: every first Tuesdays of the month we came here because it is easier for us to ask the planners or the decision-makers to come and meet activists here. We act here as mediators, and we can actually bring people together quite easily. We also organise many events in this space, many workshops and lectures about certain projects. We always announce it on the activists’ webpages. Recently we talked about a central road in Helsinki transformed into bus lanes and bicycle lanes only, and as we know that there is a large group of activists promoting cycling in Helsinki, we asked the activists to come here.

Sometimes we call Laituri an urban laboratory. It is easier for people to approach us in this place, in the heart of the town than to go to a municipal office space. We are hosted by the city of Helsinki but it feels more neutral to come together here and work on the plans. We have done customer service and mystery shopping here and we noticed that it is only a quarter of the residents in Helsinki are actually actively involved in town planning: a huge majority of people do not care for it. Sometimes it means they just accept decisions, or they are happy with the plans; or sometimes it means they are happy that it is up to the politicians or they are happy with local resident groups who represent everybody. But if we work with town plans, sometimes only the active 5% of the population represents the city and this is one of the problems we also try to solve in the next years to come.

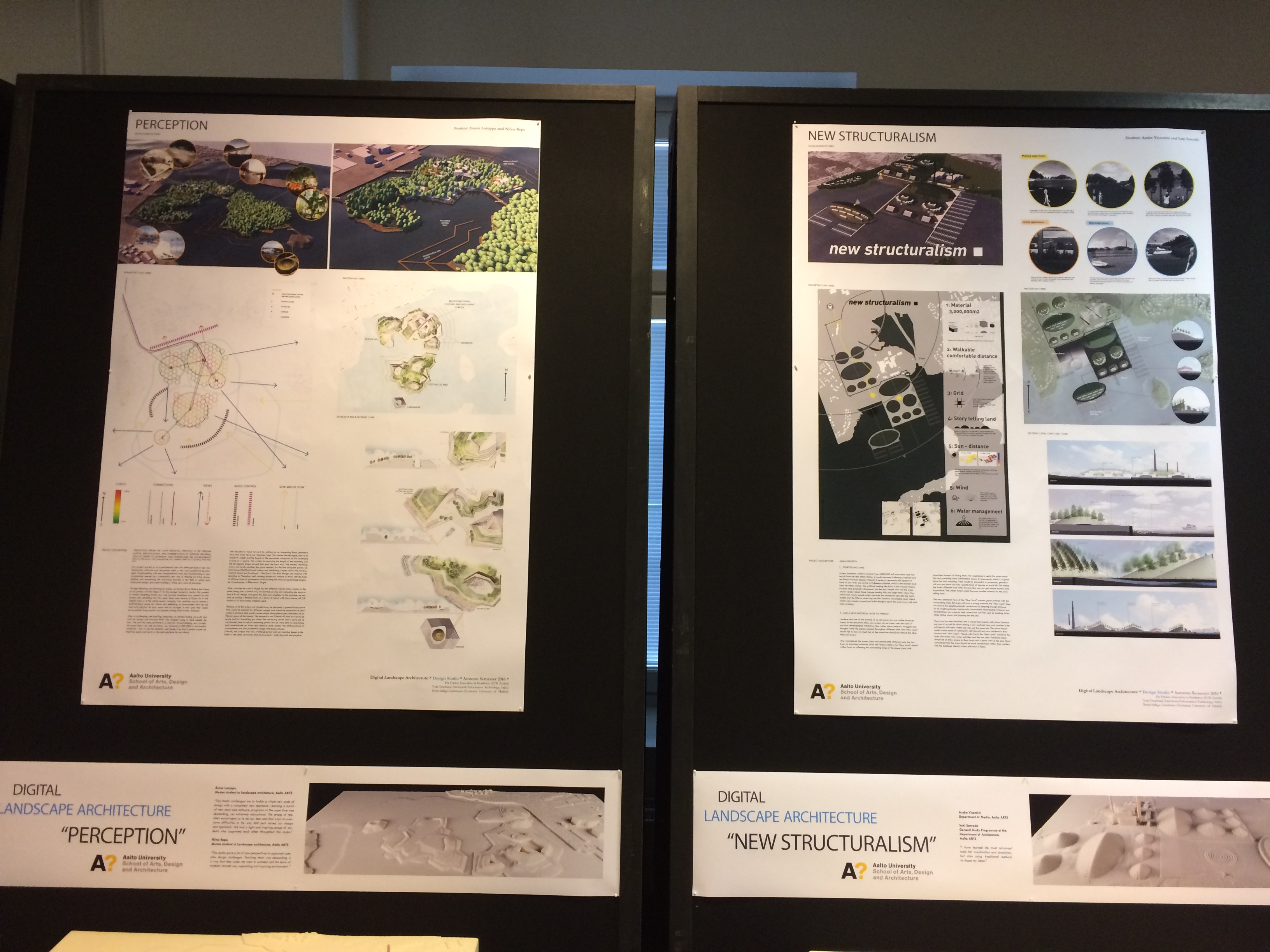

In Laituri, we make strategies alive. For instance, last year we focused on light rail, bicycle mobility and traffic in Helsinki. This year our focus is on the new part of the city boulevards. It is part of the town plan that we have to accommodate more residents in Helsinki and at the level of strategic planning, it is decided to make highways more boulevard-like: with less space for high speed car traffic and more space for light rail and residential buildings. This autumn, we have produced a large exhibition here about city boulevards. We did not make it alone ourselves but invited different interest groups to come and work on the ideas: we combine researchers from the local universities with groups of youth, local residents and businesses to create a social acceptance for the city boulevards. We noticed that in Helsinki, many people are resisting the idea, they are afraid that there will be a lot of traffic jams and that their everyday trip to work will be too long. We do not agree with that so we have to find solutions together with the public. So what we work on is more of problem solving clinic than an exhibition that presents answers.

Who is the public of Laituri?

We receive here a lot of groups, some from Finland, some from abroad. When Taipei become the Design Capital of the World after Helsinki, they asked: ‘what do you need this space for? If you are already active in the websites and forums and social media, twitter, Instagram, why do you want people to come here?’ Our feeling is that we cannot really make compromises in social media. Every time we open a discussion we receive hundreds or thousands of comments, but we cannot really create anything from them. It is so easy to point out difficulties in Facebook pages but not so easy to solve them. That is why we want to keep this space here because it is easy to invite different interest groups here and start roundtable discussions.

But people are also very active online. For example, there is a Facebook group called More City to Helsinki – it started with a couple of green politicians who wanted to have support for the new town plan but the group extended beyond any political boundaries and nowadays they have between 10,000 and 15,000 members, and the discussion is quite active. This has been a huge change in Helsinki: 10 years ago the atmosphere was basically dominated by “nimbies" who said: ’not in my backyard!’ And now there are a lot of people who are shouting, ‘build more, extend more‘. This is also quite interesting because we have to find a balance between these two groups.

Localised questions are also are on the table in Helsinki because the city has grown. The metropolitan area has more than 1 million people, we are dealing with the fact that the city council may not represent everyone. There are some city districts, for instance, that have not had a member in the council for 25 years. It is also a question of segregation. Helsinki is very equal but we reached just a point where we have to think about not just ethnic minorities, disabled people but also geographical areas that had different development paths.

And then activism is really the name of the day. Helsinki wants to become a city that creates a platform for activists to act. It is seen as a resource. The city does not need to be the one that acts, we can let the active citizens do the work for us. Also in the terms of the cultural field, Helsinki wants to be more active than it has been before. Helsinki was the Design Capital of the world in 2012 and part of the idea that design and culture can be used as a resource and a driving force came from that. Many of the seeds that we had sown then are blooming now. The idea is that in the future Helsinki can become more open and more and more engaging.

Levente Polyak

Ad hoc Expert

Submitted by fvirgilio on