How places of heritage in our cities can be drivers for local economic development by ad-hoc expert Wessel Badenhorst

Edited on

08 February 2022European cities are often blessed with places or quarters of significant heritage value. Many of these places can only be maintained and sustained if new purpose and uses can be found for them. In the Kair s Project partner cities are actively examining the possibilities for repurposing heritage with a zest for creative fusion of the old and the new, the sacred and the unexplored.

During the Project’s second transnational meeting (TNM) held on the 19th and 20th of May 2021, the partner cities focused on the theme of Heritage as a driver for innovation, entrepreneurship and job creation.

By delving into case studies from five cities in Europe and listening to entrepreneurs who are embracing heritage aspects as core components of their own businesses, participants were able to seek answers to the following questions:

• What are good practices and strategic actions to help revitalise historical quarters of cities?

• How will a focus on repurposing heritage places for new economic activities benefit from collaboration between key local stakeholders?

• Is there an encouraging return for private companies to invest in heritage buildings and to cover the costs of restoration?

• If heritage places help to define the authenticity of a city, how can this value be leveraged for economic benefits?

• Who are the users and beneficiaries that can give new meaning and ‘currency’ to uses in heritage places?

Šibenik Case Study

The city of Šibenik in Croatia hosted the online meeting. Their team led by Petar Mišura presented several perspectives on how the city is dealing with the challenges and potential of its historical quarter. Participants were first treated to a virtual tour of the city’s historical quarter and specifically, they were given a flavour of the retail and elements of interest for tourists. The city has been endowed with well preserved architecture and a history which adds to its attraction as a destination.

As with most cities along the Dalmatian Coast, the historical quarter is extremely popular in summer and then ‘empties’ out of season. To deal with this challenge, the city is hosting a number of activities and events in the quiet months. An example is the Christmas market which principally targets the inhabitants as customers. In her presentation, the event organiser, Morana Periša, explained that the market showcases local crafts (There are 231 craft traders in the city) while also hosting over 100 events in a period of 28 days. Many of these activities are spread across the public spaces in the historical quarter and are aimed at children for example in creative workshops using waste materials.

There are significant constraints in the historical quarter that restrict the type and scale of businesses. These constraints are mainly related to space management and special conservation rules. Within such a context, the good practice is to build on the strengths and minimise the weaknesses of the place. In this regard, the city is renovating its world heritage monuments namely the historical fortresses (St Michael’s, Barones and St John’s), to each exhibit a new function with enhanced visitor attraction potential. Work and jobs are also being created with contracts for renovation of facades and roofs of other heritage buildings in the centre.

The Covid19 pandemic had a devastating affect on tourism in Europe and cities like Šibenik had to plan for alternative economic activities. The welcoming of digital nomads was one such an initiative. Diana Mudrinić of the Trokut Entrepreneurship Hub in the city explained that the absence of tourists because of the pandemic meant the city had an abundance of accommodation at affordable rates.

Who are digital nomads? People working digitally who can work from anywhere but who seek places suitable to their lifestyles. Trokut is marketing Šibenik as a destination for nomads who are software developers, UX/UI designers, app developers, online marketers, graphic designers, gamers, social media experts, crypto developers, financial advisors and IoT experts. The lifestyle on offer is a relaxed, safe, family friendly coastal setting with high speed digital connectivity and great international transport connections by bus, ferry and plane. Trokut supports digital nomads with a co-working space, a welcoming tech community and with acquiring visas and work permits.

Cesena Case Study

The city of Cesena in Italy is blessed with beautiful architecture reflecting its prominence in the Renaissance period and exemplified by the world heritage Malatestiana Library. It is asking the question how to get optimum value from its heritage buildings for new economic activities.

The opportunity came to re-use the Casa Bufalini, next to the Malatestiana Library when the Region of Emilia-Romagna allocated funding to establish Open Labs in the region’s cities including in Cesena.

Through its Integrated Projects Office the Cesena Municipality started a participatory process with the aim of involving local stakeholders to co-create the ideas and uses for these facilities in the context of an urban development strategy for this historical part of the city. Elena Giovannini explained how a ‘Design Sprint’ was organised where participants from stakeholders ranging from enterprise to culture to academic to community deliberated on what services could be offered in the Open Lab and how business start-ups could be supported.

The emphasis was as much on creating networks and human supports as on establishing new facilities. The redevelopment process has been completed, but the Covid19 pandemic has temporarily halted the full use of new facilities which now include co-working, event, exhibition and meeting spaces.

Pori Case Study

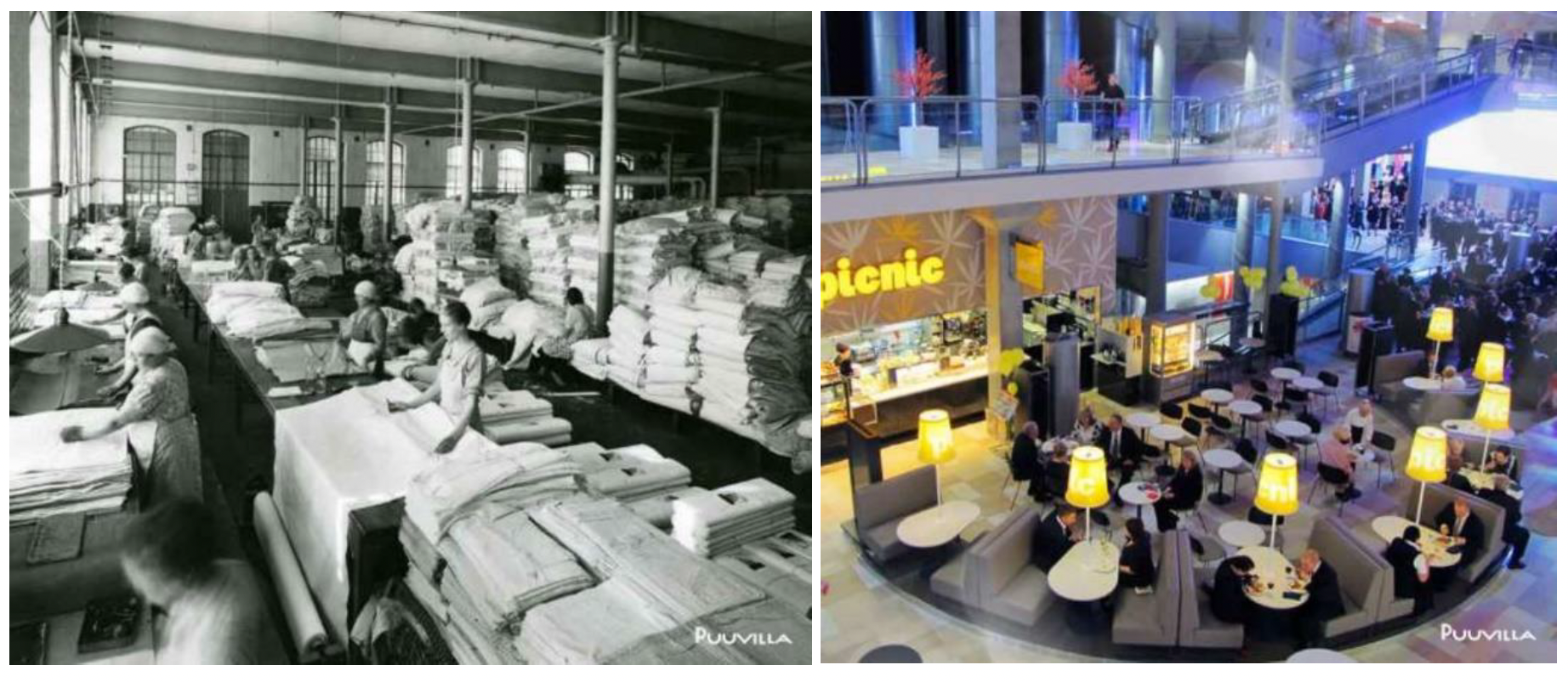

The city of Pori in Finland has a proud industrial heritage which can be witnessed in the museums of two of their famous 19th and 20th century industrialist families. The city also has managed a number of economic transformations from timber to metal works to robotics. As the eras change existing buildings need to be reconceptualised for new uses.

Mari Antikainen of the economic development company Prizztech explained the economic benefits that have been realised for the city in the fifteen years since the restoration of the old Puuvilla cotton factory which was devastated by a fire. The restoration included the development of a number of new facilities including a shopping centre, a university campus, a community youth centre and offices for start-up businesses.

A key strategy was to engage local communities in utilising the spaces. This started with the Pori Jazz organisation using the facilities when the building was just a pre-construction shell. It still continues today with many of its open spaces used for community activities.

What makes this remarkable is that it is a private sector development with an emphasis on social and environmental objectives, which is also profitable, given the popularity of the Puuvilla centre. The owners’ philosophy is to make it a green centre and today it has the largest solar roof installation in Finland. The centre is also served with high frequency shuttle buses from every part of the city, meaning every inhabitant can easily get there.

Medina del Campo Case Study

In the centre of Spain lies the city of Medina del Campo, with its rich history of the era of Queen Isabella of Castile. It is also the city of one of the famous European bankers of the sixteenth century, Simon Ruiz, who was an alderman of the city and where he left as a legacy a major hospital built from 1592 to 1619. Today this famous hospital is being revived as a centre for enterprise.

As Alberto Lorente Saiz and David Muriel Alonso noted, the life of this building is now coming back to the original economic development activities of its founder more than four hundred years ago. This was only made possible through collaboration between the local authority, government agencies, local businesses, schools and non-governmental organisations in the city.

The city has a culture of collaboration which goes back to the formation of its Medina 21 coordination structure more than twenty years ago. In all major developments in the city the citizens are involved through participation in forums to discuss ideas and to volunteer their own time and resources. In this development the building was obtained by the Museum of the Fairs Foundation in 2000 who worked with the City Council to secure EU funding for the restoration. Learning from other cities in URBACT projects (City Centre Doctor and iPlace Projects), proposals were put forward to create new facilities such as co-working and meeting spaces to attract entrepreneurs. The showcase for the new facility will be the establishment of a new business school.

Naas Case Study

Expect the unexpected. This is the motto of McAuley Place in the town of Naas in Ireland.

So often, when new facilities are planned the focus is on the future generations, when we should also include ourselves growing older and needing spaces where we can live full lives after retiring. Participants in the TNM were privileged to hear one of Ireland’s celebrated social entrepreneurs, Margharita Solon and Dick Gleeson, a fellow board member of the social enterprise McAuley Place, which provides among other things, housing to 59 older people right in the centre of Naas.

Margharita explained how deeply flawed housing for older people can be where ‘dead environments’ are created expecting inhabitants not to do anything all day. It is unhealthy not to have regular brain activity. Her approach is exactly the opposite where inhabitants will not know what the day holds as there are so much to do with a number of activities taking place simultaneously in the facility. For example on any day a wedding may take place in the chapel, while ballet classes are happening in the hall and creative art activities take place in the new community lounge. And if inhabitants want to travel internationally the airport coach stops right in front of this former convent.

What makes the enterprise sustainable is that several activities for example the tea rooms and chapel facilities provide revenue streams while the rent for inhabitants remain affordable.

In conclusion, all five case studies demonstrate that the regeneration of heritage buildings can be economically beneficial to the city if ways are found to connect entrepreneurs to the revitalisation processes. As Tiago Ferreira, Executive Director of Invest Amarante pointed out each city has to discover its own niche and advantages to be able to build trust and confidence among local stakeholders so as to be competitive. The heritage of the city is a critical aspect of this advantage and should be strategically managed accordingly.

The lead expert of the KAIRÓS Project also gave a perspective of the future where cultural heritage will ‘meet’ data and virtual realities giving new opportunities for entrepreneurs. Projects like the KAIRÓS Project are critical for local stakeholders in our cities to begin to imagine that future.

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on