How are urban gardens managed in the three RU:RBAN Lighthouse Cities?

Edited on

26 September 2022Governance is considered by the URBACT Programme a crucial component of the Good Practice (GP) of Rome. This GP can be improved and enriched thanks to the exchange of experience with the lighthouse cities, cities that will also significantly inspire the Sustainability Plan of the GP.

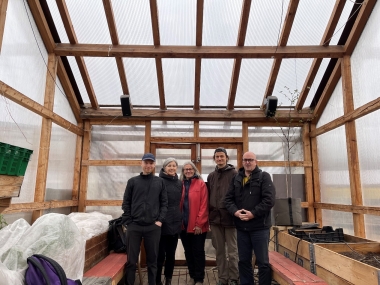

For this purpose, Lead Expert Kostas Karamarkos and Ad Hoc Experts Silvia Cioli and Fiammetta Curcio visited the three lightlhouse cities - Helsinki, Oslo and Reykjavik – between May and September earlier this year. They had the opportunity to meet with urban gardens representatives and visit selected case studies managed through models that are different than those seen during the 1st and 2nd waves of RU:RBAN. Let’s see some of the highliths of these visits!

Helsinki

Associations and communities can lease land areas from the City for small-scale urban farming. Plants are cultivated in growing containers, in growing beds, in growing bags or on small patches. Individual city residents can directly contact farming associations or establish their own community for urban farming. Locations suitable for farming are listed in the Urban farming locations in Helsinki. The requirements to lease an area are an application form to be sent via email to a dedicated email address, together with a map of area to be leased and a description of the intended purpose for the area. More information can be found at

The Case SThe Case Study of DODO

Dodo is a Finnish environmental NGO. It addresses environmental issues to the community and started its Guerrilla Gardening project in 2009 with a garden on the wasteland by the main railroad tracks in Helsinki, Pasila. The purpose of the initiative was to promote awareness on the ecological and social aspects of food. The urban garden project included not just the greenhouse, but also an apiary, cultivation beds, a summer café with a terrace and a market. Today they also organize urban gardening courses. DODO is currently cooperating with other Finnish organisations and projects around the country. This NGO has strongly influenced the landing of the urban farming trend in Finland, and today DODOs’ volunteers are working on spreading the inspiration to increasingly ecological and accessible urban gardening. More information on DODO can be found at https://dodo.org/en/cities/helsinki-en/

Oslo

Oslo is a thriving agricultural city where we can find allotments and school gardens, rooftop gardens and even innovative indoor growing projects.

The Case SThe Case Study of Losæter

Losæter was established as early as 2011, initially as an art project. The area was extremely rocky so the park was created from scratch with soil brought in for the purpose. Today the area consists of fields with traditional grains, compost, a public baking house and a horticultural therapy project. Losæter is managed by a municipality employee, considered the “gardeniser” of the park, that was not trained for this role but thanks to his experience and knowledge the area is well managed and considered as the heart of urban gardens in Oslo. The city administration supports the operational expenses of the project.

Losæter is an example of how bringing soil into urban environments can transform a derelict area into a thriving, green social meeting place where citizens can learn about ecological systems and sustainable agriculture practices through workshops, courses and festivals organized in the park. Losaeter is considered a practical learning platform.

RU:RBAN experts selected Losæter initiative because it was created thanks to the efforts of many organizations, volunteers and the city’s gardeniser.

The City of Oslo is responsible for its management, following a clear regulation that assures proper coordination of the garden’s needs between volunteers, associations and other citizens’ groups, and the preservation of Losaeter’s philosophy: the gardens are open to all, no plots are assigned to anyone. More information on Losaeter can be found at https://loseter.no/home-page/?lang=en

Reykjavik

The Sustainable Planning Policy of the city aims at maintaining Reykjavik as an internationally leading green city.

Community gardening in Iceland is mostly run by the municipalities. The phenomenon started in 1948 with school gardens for children aged between 8 and 12. In 2011 the school gardens became family gardens. Today some of these gardens are run by associations or community groups. The municipality of Reykjavik supports citizens with workshops provide advice and free education on growing herbs and vegetables Reykjavik leases out about 600 vegetable gardens. Access is given to the vegetable gardens each year in May and citizens can apply for a vegetable garden by sending an application form by the end of April.

The citizens of Reykjavik are not put off by the weather conditions as they connect the activities in urban gardens to a high quality of life. The COVID-19 pandemic also encouraged Icelanders to be more active in urban gardens projects. A very interesting urban garden in the city is located in the area of Kópavogur, an excellent example of management system by the municipality that includes the use of maps, scientific data and a supporting office for citizens engaged in the urban garden. More information on Reykjavik urban gardens can be found at https://reykjavik.is/en/vegetable-gardens

Submitted by Patricia Hernandez on

Submitted by Patricia Hernandez on