Heritage-driven urban development and regeneration. The KAIRÓS journey - by Lead Expert Miguel Rivas

Edited on

26 January 2022Heritage valorisation nurturing urban development

Two major changes are impacting the heritage field over the past years. The first one is about a change of scale. Today, the spotlight is not so focused on the building and the monumental artefact, but also on the urban fabric and the idea of cultural landscape, which became doctrine in 2011 with the adoption by UNESCO of the recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape.

HUL is defined as “the urban area understood as the result of a historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes, extending beyond the notion of historic centre or ensemble to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting”. The second is a change of purpose, meaning that valorisation [and eventually adaptive reuse] matter now as much as preservation. Thus, the best preservation policy is that of reconnecting heritage to the contemporary city, in terms of use and function. Hence, more than just a stock of the past, heritage is now addressed as a history of transitions, and should be properly managed as such. Such a transitional or dynamic approach understands heritage as a living memory, and therefore valuable to build the future. This idea fits that of circularity and sustainable development.

Ultimately, both changes have led to a change of method. That is, as a result of the above, heritage is increasingly addressed at the crossroads of several fields —e.g. culture, urban planning, tourism, society and wellbeing, economic development. Consequently, an integrated approach is needed more than ever to tackle the multi-faceted nature of heritage valorisation. All these changes are converging on the idea of heritage-driven urban development and regeneration.

Upon these assumptions, seven medium-sized cities —Mula (ES), Šibenik (HR), Ukmergé (LT), Cesena (IT), Heraklion (EL), Belene (BG) and Malbork (PO)— promoted KAIRÓS in 2019, as an URBACT Action Planning Network. The ambition was to build up the aforementioned integrated approach by assembling five key dimensions —Space, Economy, Attractiveness, Social Cohesion and Governance— in order to fully realize the potential of heritage as a driver for sustainable urban development. After two years of international peer learning feeding local action planning, this KAIRÓS five-pillar model has proved to be workable to a variety of different circumstances and local needs. For instance, Cesena´s Integrated Action Plan [IAP] is called “The City Gate”. It aims to reuse the city´s industrial legacy (notably the former Arrigoni factory complex) as the spatial foundation for the re-development of the area surrounding the train station. Heraklion, the administrative capital of Crete, is facing a prototypical problem of dereliction, shrinking population and social problems in the historic quarter of Aghia Triada [picture below]. The challenge for Malbork, in Poland, is nonetheless quite different from the former ones. Malbork´s destination experience is reduced to visiting the iconic Teutonic castle [UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most visited tourist attraction in the country], which has little impact on the local economy and underestimates other cultural assets. So, a city perspective is needed in Malbork to look at cultural heritage, and the five-pillar model is providing a useful framework.

[New] Planning formats in urban regeneration

Besides this overall assessment of the KAIRÓS method, other key points can be highlighted from the work done so far. The first is to acknowledge the primary role of the Space dimension in heritage-led urban regeneration —i.e. preservation and production of urban form. Both, preservation/valorisation of built heritage and production of new urban space, can mutually reinforce, in a sort of dialectic relationship. Thus, regenerating Aghia Triada [with a badly degraded housing stock] does not entail preserving everything at all costs, not to mention removing collapsing dangerous buildings. New [contemporary] needs in terms of accessibility or public space may demand specific changes over the inherited fabric. Valorisation must be seen from the scale of the neighbourhood. We learnt this from Anne-Laure Moniot, head of architecture at Bordeaux World Heritage [the largest urban area enlisted as UNESCO World Heritage Site], who was invited to the KAIRÓS discussions. Talking about the kind of planning they are applying to central Bordeaux, she says “it is not only the conservation plan but the plan also identifies where the opportunities are (to continue making the city)”.

Space should be at the core of the urban regeneration project, and we refer to the practice of architecture, urban planning and urban design basically. The urban/architecture project is at the basis, conditioning everything, positively or negatively. It provides the physical setting to then build up the intended integrated approach. At this point, it should be noted that (still timidly) some urban planning figures and practices are emerging in the regeneration field, other than land-use planning and conventional master planning. In a way, they are reconciling hard planning [that of holding a strong regulatory power] and soft planning, and the KAIRÓS cities are now testing to what extent the URBACT figure of Integrated Action Plan has the capability to play this role somehow in a context of urban regeneration or area development.

Just like that, to stop and revert the vicious circle of degradation that is affecting the so-called historic Barrios Altos, the Spanish town of Mula (lead partner of KAIRÓS, picture below) is drafting an Integrated Action Plan made up of 15 actions organized in four strands: Housing, Public Space and Accessibility; Entrepreneurship; Rebuilding Attractiveness; and Social Cohesion. Out of them, 4 actions taken from the first strand have already been prioritized for their capacity to break the current inertia and presented to the Regional Government for financing. They amount 17 million Euros of investment.

At this point, the question of housing deserves a special attention. The work done in most KAIRÓS cities reveals that there is no effective urban regeneration without addressing affordable housing, as well as other related issues such as re-appropriation of the public space, temporary use for vacant spaces or new approaches on urban security.

Setting aside (just for a while) the undeniable relevance of getting a proper planning framework, some specific urban interventions can spark by themselves the benefits of heritage valorisation and make a turning point. In Šibenik´s old town —which is affected by depopulation, tourism-driven gentrification and lack of urban vitality during the low season— the restoration and reuse of St. Michael historic fortress has worked in that way. The fortress, which offers a dominant view over the old town and the Adriatic Sea, has been refurbished and repurposed as a breathtaking open-air stage and auditorium and exhibition centre on Šibenik´s history. Less obvious than the former but with a stronger tractor effect, it is the spatial re-configuration of Poljana square [picture below] as a big promenade at the entrance of the old town, including a three-storey underground parking, which has dramatically improved the accessibility to the historic centre.

A social-driven approach to cultural heritage valorisation

A second main finding arising from the work done so far in KAIRÓS is that promoting a better social access to cultural heritage is key to unlock the potential of heritage as a driver for sustainable urban development. Furthermore, a social-oriented approach has the effect of expanding the portfolio of heritage valorisation projects in the city, and is key to build up a relevant city perspective to cultural heritage.

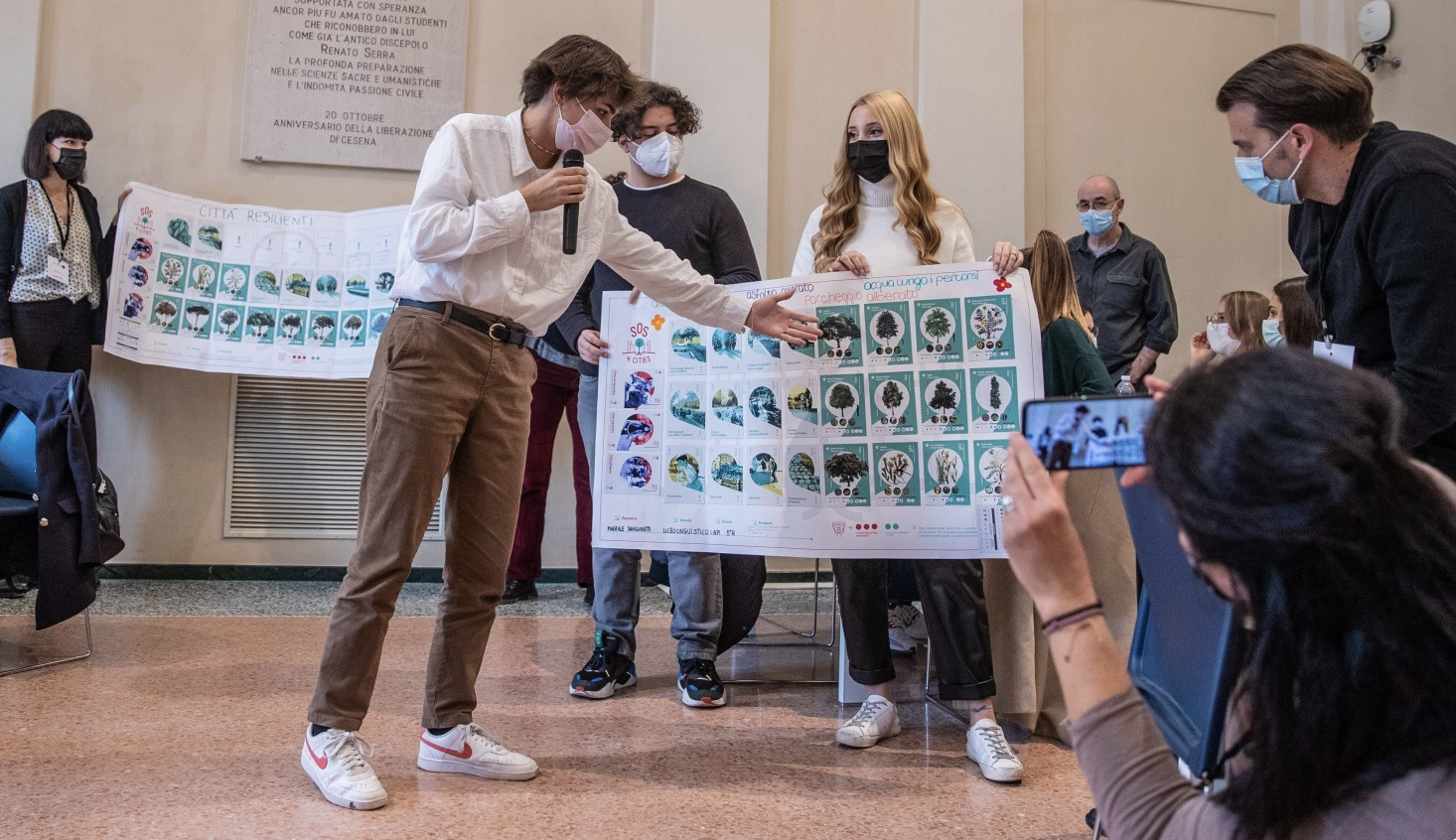

In turn, it leads to adopt a participatory approach, which makes a difference in today´s heritage-led urban development. Opening specific dialogues with specific groups of city users [e.g. youngsters, elderly people, shop owners…] can certainly boost new ideas and solutions to then consider in the set of actions. Indeed, a good number of small scale actions [SSAs] delivered by the KAIRÓS cities over the past year were focused on stimulating that user-centred dialogue. In Cesena, the SSA took the form of a living lab where high school students teamed up to explore urban solutions for the KAIRÓS target area [picture below], resulting in a significant reinforcement of the nature-based type of solutions. “Multicultural Reverberations” was the name given to Mula´s SSA. They used its drumming tradition to foster the multi-cultural dialogue, as means to face the ghettoization of the Barrios Altos, with a now prevailing low-income immigrant population.

In fact, the very Integrated Action Plan of Ukmergé [Lithuania], in the framework of KAIRÓS, is quite focused on empowering civic society for the old town´s revitalisation. The stagnation of Ukmergé´s old town over the past decades has made this place unattractive to people´s imaginary, and surprisingly this central area was not an option for many to live in. A too rigid heritage preservation regulatory framework was working as an additional hindrance. The big challenge is now to organize and develop a comprehensive strategy for the integrated urban regeneration of the area, providing a framework to the number of physical rehabilitation projects promoted by the Municipality and raising the confidence and interest of dwellers, investors, shop owners and entrepreneurs. In this attempt, it is absolutely necessary for the Municipality to build up a participatory approach that is now inexistent. On the one hand, the Municipality feels the need to have a credible civic counterpart to discuss and agree with. On the other hand, the local community needs to be re-energized, and the KAIRÓS Integrated Action Plan is being a precious opportunity to take a giant step in this direction.

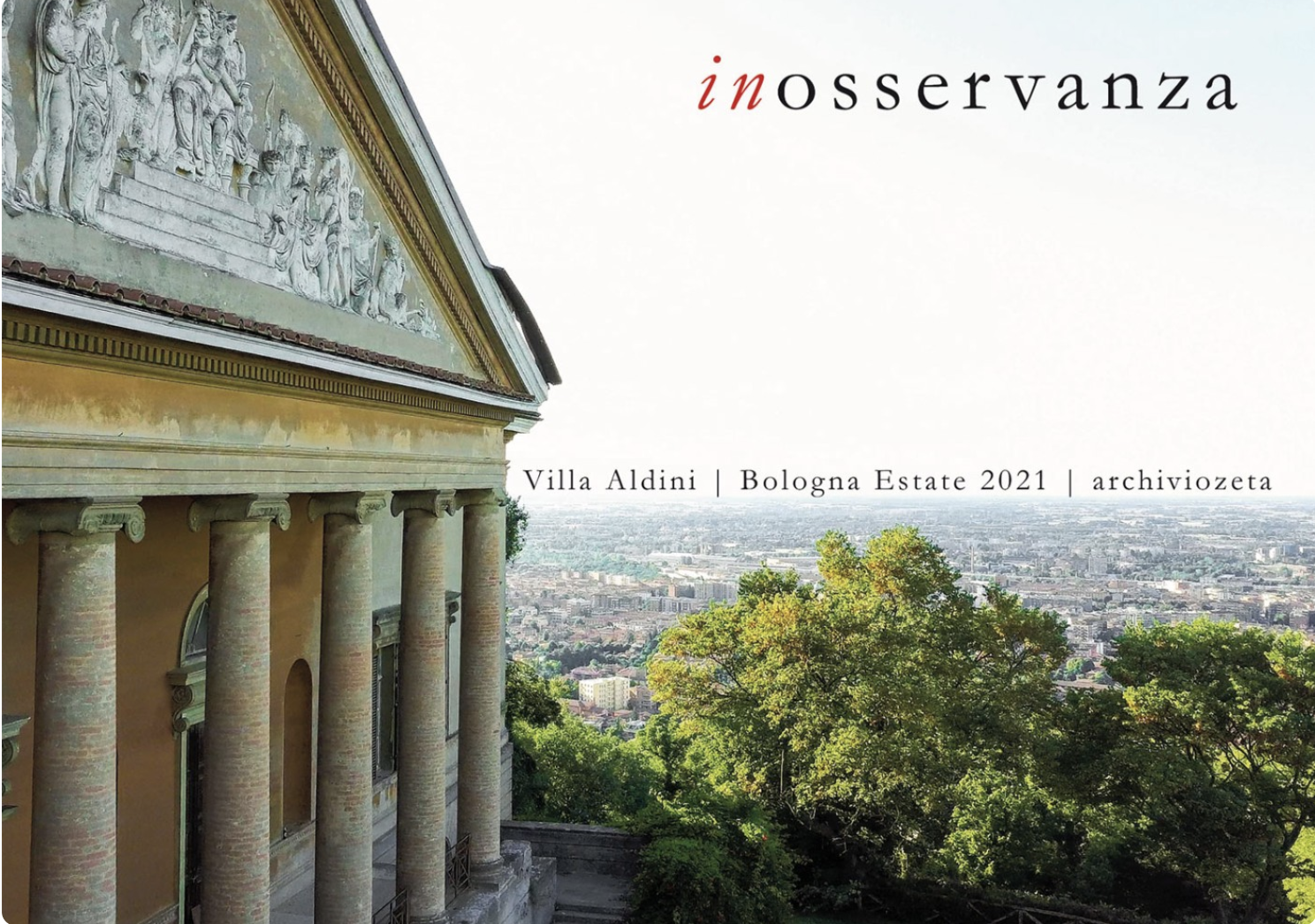

Those social and participatory perspectives are related somehow to an experimental approach, in the sense of facilitating proofs of concept when tackling the heritage valorisation projects. This was a main lesson that we got from the study visit to Bologna, organized by KAIRÓS together with the Municipality of Bologna in November of 2021. An example is Villa Aldini, an abandoned Napoleonic mansion on the city hills, which is the subject of a major regeneration and adaptive reuse project. The decision to regenerate Villa Aldini is firm and has no way back, but the Municipality of Bologna is not in a hurry. They are now in a sort of initial stage of experimentation to find out how the place and the surrounding green area can be best appropriated and used. To that aim, the mansion is being offered to temporary cultural events and residence for artists [picture below] It is like a “consultation to the market”, in order to give a more solid base to the adaptive reuse project.

In the same vein, the Municipality of Bologna was promoting some temporary interventions of “tactical urbanism” aimed at getting some historic squares free of the massive car occupation. As the test was enthusiastically welcome d by the people and the local media, those interventions were turned into permanent and scaled up to other historic districts. Including experimentation at the initial stage of the heritage valorisation project, no matter the scale, is a reason to validate the usefulness of the URBACT concept of small scale action as an ingredient of the action planning process.

Spreading the word

To share these findings and more, the KAIRÓS network has been invited to the international conference “Heritage for the Future/Science for Heritage” that will be held in Paris in March 2022, under the French presidency of the EU. The event is organized by the Foundation for Heritage Sciences and the European Commission, in partnership with the French Ministry of Culture and the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS).

There, we will spotlight the meaning and scope of the integrated approach in heritage-driven urban regeneration, as a triple endeavour: policy mix, leading to organizational adjustments to break the silos thinking and performance in the local state; stakeholder involvement, leading to a more participatory or relational style of governance; and multi-level governance, meaning better alignment and funding orchestration. As for the latter, there is no urban regeneration without a significant public investment. Indeed, fundraising will draw our main efforts from now till the end of the KAIRÓS journey.

Miguel Rivas | Lead Expert for the KAIRÓS Network

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on

Submitted by Dorothee Fischer on