Gender equality at the heart of the city

Contact

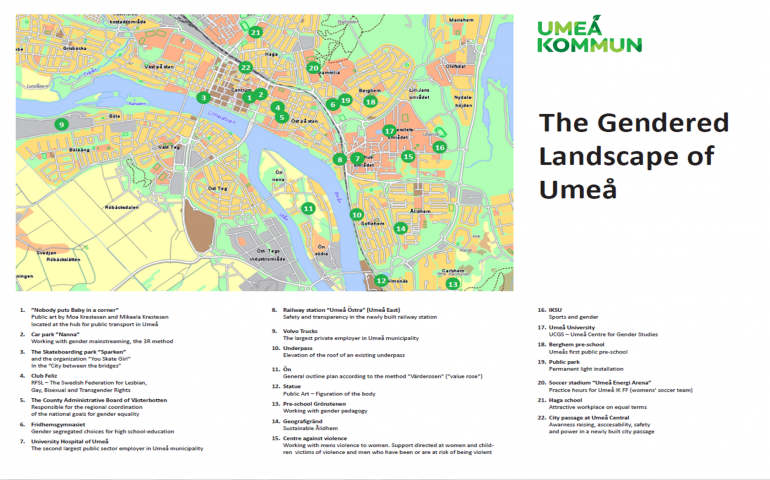

What do a bus station, a park and a tunnel say about equality and gender issues? With the objective to underline the importance of gender equality and to show actions and results of a long-term work in the city, Umeå (SE) created a "Gendered landscape". Since 2009 guided bus tours around the city show to passengers successful changes in the city, and put light on still existing gender inequalities. This practice raises important questions about the city’s development and identity issues. How do we build new tunnels, playgrounds, meeting places, recreation centres? Do we plan our public transport for those who use it or for those we wish would use it? Why are women using public transport more frequently than men?

Since 2009 the city of Umeå provides guided bus tours around the city to show “the gendered landscape of Umeå”. This is an innovative way of showing how working with gender equality takes form in a city - exemplify successful changes and work in the city, as well as illuminating remaining issues. In line with Umeå’s high ambitions on sustainability and gender equality, the gendered landscape method has been developed in Umeå, and, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first of its kind in Europe.

The method is not about traditional neighbourhood safety/security surveys, it is about taking the city itself as the starting point, highlighting gendered power structures throughout the city and how they can be understood and transformed. The method of "the gendered landscape" is being used for educating and creating awareness on the importance of a cohesive understanding of gendered power structures concerning all urban planning in the city. The method raises important questions about the city’s development and identity issues that are critical norms and, in some cases, provocative as well as challenging and dynamic. How do we build new tunnels, playgrounds, meeting places, recreation centres? Do we plan our public transport for those who use it or for those we wish would use it? Why are women using public transport more frequently than men? Who has the power to decide? What knowledge do we use when we are working on developing the city and our public spaces?

The idea of the Gendered Landscape is to highlight power structures in the city, to focus on the city in itself rather than specific groups in the city, and to have an integrated understanding of inclusion, gender equality and sustainable urban development. Different stakeholders are represented at the stops of the bus tour, as well as different levels of government (i.e. highlighting the cooperation between local, regional and national level in working with gender equality through the bus stopping, for example, at the county administrative office).

This approach leads to a better understanding that a city, to be able to be transforming, must develop new initiatives and projects with an understanding of the context of the city and an understanding of gendered power structures. The Gendered Landscape approach highlights the need to have qualified staff within the city administration involved in all urban development issues within and outside the city administration, and not exclusively focusing on representation issues, etc.

In this respect, a good cooperation between Umeå University (for example the Umeå Centre for Gender Studies) and the city of Umeå is seen as one key component.

The tour is a way of making the statistics in the “Gendered Landscape” report come alive, currently outlining 25 integrated practices in the city, and an innovative way of demonstrating the concrete effects of striving for gender equality. The work has been led by the municipality, but also by other organisations and persons. The idea of the tour is to highlight the city as one and the need for cooperation and collaboration in creating an inclusive city.

One example is the park “Freezone”, a collaboration between different parts of the municipality and groups of girls in the city. The collaboration led to a better understanding of expectations that young women deal with every day and the need for public spaces where nothing is expected of you. With this new knowledge, a park was built in the city centre.

Collaboration between the municipality, Umeå University and the Swedish for immigrants-school led to an understanding that there is a difference between being seen and feeling like an object or a subject in public spaces. How do background, age, gender and disability figure in, and how is the city planned?

This led to changes in how public forums are arranged in the city to insure that more inhabitants take part in the process. Both these examples are part of the Gendered Landscape tour which also includes places with work that has been or is being done by NGOs, public works of art and highlighting the constant interactions between public and private that are present in a city.

There are several examples of how the initiatives of the bus tour have made an impact in the planning and development of the city. The Freezone initiative has impacted the work of the Umeå Street and Parks department, changing their methods for dialogues with citizens and gender-mainstreamed the content of steering documents. Another example from the tour is the example of Gammliavallen football stadium and the city’s ambition of a more equal use of public spaces and sports arenas. In 1999, a political decision in the municipal board of leisure led to that practice hours were divided according to what division soccer teams played in, regardless of gender. As a direct result Umeå’s leading women’s soccer team, Umeå IK, got to choose their practice hours before the leading men’s team, Umeå FC. Since then, the decision has impacted the distribution of practice hours in all municipal arenas in Umeå.

A third example is from Umeå as a cultural city, where the cultural sector continually monitors gender representation in the city cultural scene. A positive trend towards more gender equality is observed over the last few years. In 2015 there were 45 % women (out of 2,000 events) represented on the main cultural stages in Umeå.

Thus far we have had around 30 international exchanges with representatives from European countries and around the world on the Gendered Landscape approach. The challenge of gendered power structures is shared across all European cities. The social and cultural context of the cities differs, of course, across EU Member States, but the Gendered Landscape approach offers flexibility to adapt to these different pre-conditions.

In an international context, we see that the potential to reuse the methodology is great, not least within a European (i.e. URBACT) context, as the methodology has proven to be easily adaptable to different local cultural and social contexts. Examples of international exchanges so far include:

• The European Capital of Culture (ECoC) network, where Umeå, as European Capital of Culture, has hosted a number of international meetings;

• CEMR;

• Union of Baltic cities Gender and Planning Commissions;

• Urban Development network 2014 Innovation pitch in Brussels.

We believe that the Gendered Landscape integrated approach has been successful in Umeå. The long-term ambition is to build on the interest generated thus far and implement further developments in Umeå and across Europe.

The ambition in applying for an URBACT Good Practice is to use this as a starting point for a European network initiative (possibly within an URBACT Transfer Network), inviting other parts of Europe to work together on further developing the approach in Umeå and elsewhere.