Financing the Urban Commons. Part II

Edited on

02 May 2021How can urban commons be financed? Civic eState investigates opportunities in EU structural funds and financial investment tools with the European Investment Bank

Following the first meeting on possible financing instruments for the urban commons, the seven cities of the Civic eState project explored additional tools for social finance in a subsequent meeting, especially from European Structural and Investment Funds. They also discussed tools to measure the social value of initiatives thanks to the experience of the partner cities of Barcelona and Amsterdam. They were joined by financing experts Desmond Gardner, Financial Instruments Advisor at the European Investment Bank (EIB) and by Jelena Emde, Investment Platform Advisor at the EIB.

A second meeting with the EIB

Gardner presents to Civic eState the work of fi-compass, a platform for advisory services on financial instruments under the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF), as well as two initiatives particularly relevant for the urban commons: the Mutual Reliance Initiative (MRI), a mechanism by which, when co-financing projects, one of the three partners takes the role of lead financier, relying on its standards and procedures as long as the minimum requirements of the other partners are met, and the case study of the Financial instruments for urban development in Portugal (IFRRU 2020, Instrumento Financeiro para a Reabilitação e Revitalização Urbanas), a financial instrument that has been established to support urban renewal across the entire Portuguese territory. Jelena Emde presents social outcome contracting (SOC) options for urban commons projects, an innovative form of procuring services based on outcomes, whose main feature is that improved social and health outcomes lead to a financial return for the involved parties and the saving of public finances.

It is important to note that the EIB resources are raised on the international money market. It is a powerful tool, but it is also why the EIB cannot take more risks with investments. It raises finance by borrowing money. The EIB needs to adopt a commercially based funding policy and be complemented by programmes like the European structural and investment funds (ESIF) to make it work.

The EIB group finances at a very large scale and lends heavily to national and regional governments to support infrastructure: a large amount is invested in the environment to try to tackle the climate challenge.

European Structural and Investment Funds Financial Instruments: what are they?

Desmond Gardner explained that part of the resources under the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) are turned into financial products (so-called 'financial instruments') such as loans, guarantees, equity and other risk-bearing mechanisms, which can then be used to support economically viable projects which promote EU policy objectives. Financial Instruments (FIs) therefore are different from grants because they need to be repaid. The EU Member States receive ESIF funding and then they appoint a national body known as the Managing Authority (MA) which oversees the use of the available resources and of FIs.

While grants still have a crucial role to play, FIs can offer significant advantages. Amongst the most important of them, there are: the revolving effect, meaning investments of structural funds through financial instruments are repaid and therefore can be invested again and again, providing more outputs for every euro that is committed in that way; and the leverage effect meaning the capacity to attract additional public and private resources, implying that actors can use relatively small amounts of structural funds to mobilize other resources, both public and private.

Moreover, financial instruments can also contribute to improved impact, because they are managed by independent fund subjects, who make the same judgements about the risk that you might expect a bank to do in terms of the viability and the success of the project.

Finally, FIs lead to what are often called ‘bankable’ projects – projects that generate revenue, cost savings, or growth in value for equity investments. The rule in the future for member states to choose the tools to use to invest their structural funds should be when a project is bankable and which financial instruments should be used, allowing grants to be used where there is no commercial market. It is important to understand how these tools can apply to urban commons projects, identify the bankable projects. and characterize them to develop possible financing models in the future.

A case study of a city-led fund: the MRA-RICE Blueprint City Fund

Desmond Gardner brought forwards the example of an independently-managed city-led financial instrument, developed in 2018 following a pilot with the cities of London, The Hague, and Milan.

In 2015, the EU Commission issued a call for proposals under the Multi-Regional Assistance programme (MRA). The MRA offers EU funding for co-operation projects involving at least two managing authorities from the different EU Member States selected through competitive calls for proposals. The assessment of the possible use of ESIF financial instruments in specific thematic areas of common interest is the objective of the MRA projects. The cities of Manchester and The Hague brought London and then Milan to apply this call.

Inside the MRA, the Revolving Instruments for Cities in Europe (RICE) project started to developing the Blueprint city fund to look at experiences and key features, aiming to toat further new financial instruments to increase private sector investment in urban development projects. Cities needed to go through this process:

City strategy → Project pipeline → Assessment of financing needs → New city fund (RICE)

First, everything being strategy-driven, they need to define a strategy and identify where financial instruments could play. Then, having an existing project pipeline that can be nurtured and grow is an important contribution that cities can make in developing this fund. Thirdly, they must recognize what the financing needs are, what projects are bankable, when is a grant or financial instrument the right tool, and what type of products is needed from that financial instrument. Finally, this leads to the creation of a platform, the basis to establish the new fund.

With the EIB’s help, the MRA-RICE Blueprint City Fund’s project promoters, the four cities, came up with five elements for effective city-led funds going forward: capacity, independent fund manager, structured design, products and investment-friendly.

A case study of pooling diverse investments: IFFRU 2020 in Portugal

Desmond Gardner also presented the example of Instrumento Financeiro para a Reabilitação e Revitalização Urbanas (IFFRU) 2020 in Portugal, a national scheme where the government managed to take a relatively small amount of structural funds and raise a large amount of public and private investments. Three banks are supporting the implementation of this scheme: Santander, BPI, Millenium, and SPGM, the national guarantee institution.

The IFFRU is an urban development fund that pooled resources from the European Regional Development Fund, EIB, Council of Europe Development Bank (CEDB), and from their own resources. After having gathered 702 million in public money, the government reached out to commercial banks, which agreed to match that funding.

The IFFRU is a robust model for urban development schemes in European cities because it successfully attracts both EIB and private sector finance. This financial scheme sets an example of how European investment structural funds can be used to support assets-based urban development such as urban commons.

Another option for financing the commons: Social outcome contracting

Following the conversation on financial instruments, Jelena Emde discussed social impact investing in cities, and specifically Social Outcome Contracting (SOC).

SOC is an innovative form of procuring social services, in which the service provider’s compensation is linked to outcomes rather than specified tasks (rather than outputs).

Often known as a payment-by-results scheme, it has many sub-categories, one of which is Social Impact Bonds (SIBs). SOCs are a partnership between a public authority, which defines desired outcomes and pays for those outcomes, and a service provider, who in turn works to get the beneficiaries to achieve those outcomes. In some cases, investors also play a role by providing the funding, and they are mostly involved in social impact bonds. Finally, in the structure of the SOC there is often an external evaluator who verifies the achievement of the outcomes.

SOCs are growing in importance because of their focus on prevention. It is widely known that investing in prevention pays off and that the State can save millions, but the available resources are already tied to dealing with emergencies. So this is why investors can step in. They can invest in building fences (for example for the prevention of diabetes, foster care, homelessness, etc.) and help governments save millions in the future. When the results are achieved, the savings can be used to pay back investors. While if they are not achieved, no repayment is necessary.

For SOCs to work, there has to be a solid business case behind both social impact and quantifiable savings for the government that can be achieved and generated. This is why we turned next to ways of measuring social value, with Amsterdam’s MAEX and Barcelona’s Community Balance.

The Koto-SIB Programme is a payment-by-results programme implemented by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment in Finland in collaboration with the EIF. It is the first social impact bond scheme dedicated to migrants and refugees in Europe, supporting the integration of migrants in Finland.

EIB Advisory support

Desmond Gardner and Jelena Emde are both working at the EIB Advisory department in which three financial instruments can be relevant to Civic eState.

- fi-compass: an advisory platform settled by the European Commission in partnership with the EIB. It is designed to strenghten the capacity of managing authorities and other stakeholders to work with ESIF financial instruments.

- European Investment Advisory Hub: a centre to support the identification and feasibility of using investment platforms and financial instruments, combining the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) with ESIF funds.

- Bilateral advisory, client funded assignments to Managing authorities and the National promotional banks and institutions (NPBIs) for bespoke financial instrument advice.

The opportunity for support from the EIB group includes the possibility to invest in those schemes through the European Investment Fund, which can contribute upfront funding to finance such programmes. The EIB also supports the development of SOC through advisory services. To support these projects and public authorities across Europe, they have launched in 2019 the Advisory Platform for Social Outcomes Contracting, funded under the European Investment Advisory Hub (which is itself part of the Investment Plan for Europe, the so-called Juncker Plan).

The MAEX: a foundation that calculates the social value of initiatives

Given the importance of quantifying the value of projects, both for FIs and for SOCs, the Civic e State network turned next to a discussion about how to measure impact. Nathalie van Loon, project coordinator of Amsterdam’s URBACT Local Group, talked about MAEX, a Dutch foundation that calculates the value to society of initiatives.

MAEX charts their impact and offers them easy access to public administrations, privates, and individuals by considering how they contribute to a vibrant society and sustainable economy. One tool used in the evaluation is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This framework forms a sound basis for impact measurement because of the SDG’s broad scope and international recognition.

The MAEX assessment makes the activities and impact of social initiatives visible and measurable and. organizations can also use a self-assessment tool to evaluate their own impact. This makes initiatives aware of their own ‘Social Handprint’, which can help target the search for the right type of funding. MAEX has assessed the impact of an urban common – Stadslandbouwproject NordOogs – a large piece of land in North of Amsterdam, which has turned into a commons project involving beekeeping and city farming.

Barcelona and the Community Balance tool

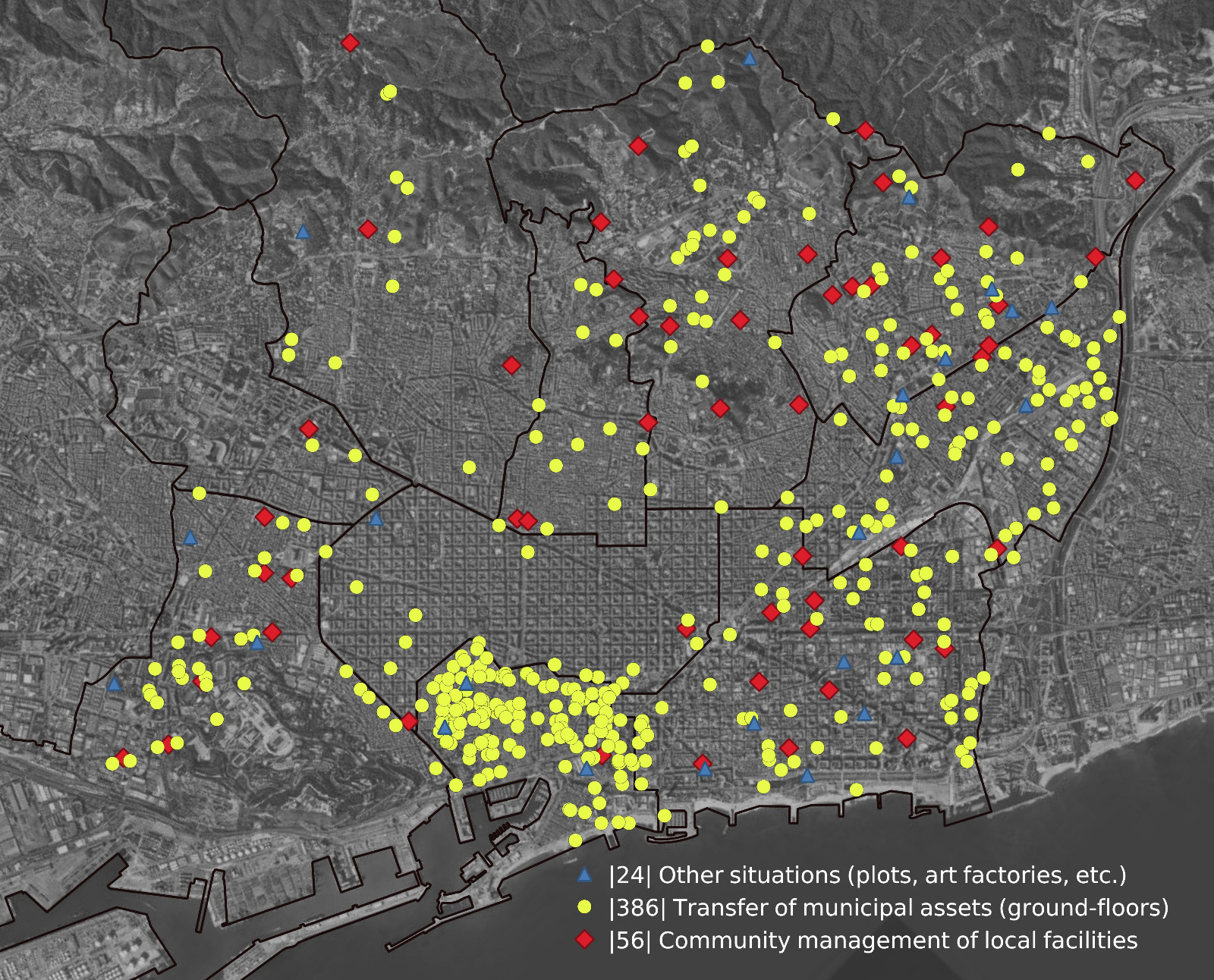

Another example of measuring the impact of social initiatives is the Community Balance tool, which Elena Martìn, Barcelona’s project coordinator for the Civic e State Network presented.

As part of the city’s Citizen Assets programme, Barcelona has developed a series of criteria or principles of what ‘community management and use’ means, as well as a self-evaluation tool for the value created called or mechanism that is called Community Balance.

The criteria for the Community Balance tool have been developed and agreed upon with communities involved in the community management experience including – the social solidarity economy network (XES), Barcelona city council, and the community spaces network (XEC) – all part of Barcelona’s URBACT Local Group. The tool assesses factors such as ties to the territory, social impact and return, democratic, transparent and participation-based internal management, environmental and economic sustainability, and the care of people and processes. The tool was piloted with ten initiatives and it will be further reviewed by the City following the pilot results.

Here you can read the first part of "Financing the commons"

Submitted by Christian Iaione on

Submitted by Christian Iaione on