Cooperative City in Quarantine: Connecting local initiatives during the COVID-19 crisis

Edited on

05 June 2020Realising the need to create international dialogue on handling the COVID-19 crisis at the local level, Eutropian launched a weekly webinar to connect activists and experts from all parts of Europe with a broader audience.

On a Sunday evening in early March, I received a few text messages. It was 8 March, and I was enjoying the final screening of the film festival I co-organise every year. Once the movie was over and I stood up, I stretched my legs and looked at my phone. A few seconds later, after I opened the messages, I realised that I could no longer ignore the threat that had been slowly spreading towards us from different parts of the world. I did not expect that screening to be my last night out and the 200-seat movie theatre to be the last indoor public space I entered for the months to come; but I understood that my work would radically change in the following period.

The messages were from a group chat that we used to plan the upcoming study visit of the ACTive NGOs network to Naples. I learned that the visit, designed for months to take us to various community-run spaces and commons initiatives across the city, had just been cancelled. The decision did not take me by surprise: several of our partners had already withdrew from the study visit in the previous days, and our space to manoeuvre in Naples looked more restricted every day. This is how, day-by-day, our life has changed, with our movements increasingly confined and most of our activities moving online.

I work in Eutropian, a Vienna-based company with employees and contributors across Europe. Working from different cities and traveling regularly to follow-up on our projects at various parts of the continent, we are used to work in distance and accustomed to using digital tools to coordinate our work. Keeping up our daily working routine was not particularly challenged by our limited mobility, although taking care of our families and the people close to us had begun to demand more and more time and energy.

But what we saw around us was frightening. In the neighbourhoods where we live and work, often defined as disadvantaged from a variety of viewpoints, many families and individuals found themselves in isolation, left behind by public services and cut off from their formal and informal safety nets. Furthermore, in the course of only a few weeks, with thousands and thousands of companies shutting down in various cities of Europe, many of our friends and acquaintances lost their jobs or saw their commissions reduced to a minimum. What took years for the 2008 economic crisis, had been now accomplished in a few weeks: entire sectors of the economy were washed away, with millions of people left to their own devices or to the mercy of government aid programmes.

We noticed quickly, however, that while many governments were struggling to find the right response to the sanitary crisis, civil society mobilised itself with surprising agility and efficiency, to bridge the gap in public services and to bring basic supply to unserved areas and disadvantaged social groups. More surprisingly than the cultural sphere always known for its social sensitivity and sense of solidarity, Budapest, for instance, has also witnessed a variety of businesses changing profile in the course of a few days. Taxi companies, rapidly losing their clients, have engaged in transporting health workers to hospitals. Airbnb apartment owners as well as hotels, in lack of bookings, have begun to offer their properties for quarantine or temporary housing for health workers. Restaurants and various event organising companies have switched immediately to home delivery and existing short chain distribution services began to flourish.

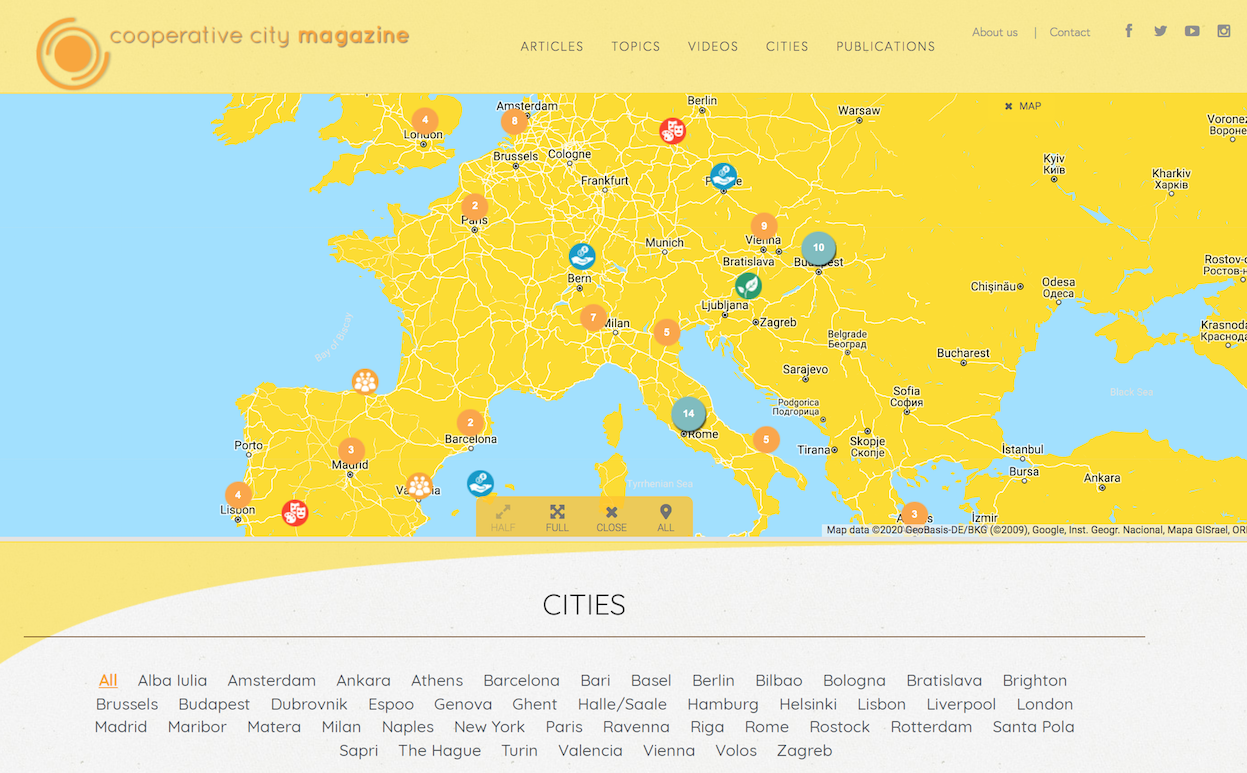

This phenomenon is by no means surprising. Years ago, recognising the crucial role played by civic initiatives in helping cities overcome the last economic crisis, we realised that while they are very important contributors to civic ecosystems, solidarity networks or social services of their cities, most of these initiatives lack the time and space to step back from their activities and tell their stories to a broader audience. We founded the Cooperative City magazine to give voice and additional visibility to such initiatives, connect them with their counterparts in other areas of Europe and help them cooperate better with municipalities and shape public policies.

The current crisis brought a new momentum for these initiatives. As Natasha Dourida from Athens-based Communitism explained us, Greece, for example, “had the advantage that the Greek society already has solidarity mechanisms and peer-to-peer connections in place from the last crisis.” Many of the projects that we previously covered in the magazine had quickly adopted to the sanitary crisis. For instance, Largo Residencias in Lisbon was quickly converted from a hotel and hostel into a quarantine facility for infected refugees. In Paris, Les Grands Voisins and other buildings in temporary use by the collective Plateau Urbain had become hubs for food distribution. The Community Land Trust Bruxelles used the moment to strengthen its solidarity network, while A Város Mindenkié in Budapest supported the Budapest Municipality in turning vacant properties into temporary homeless shelter facilities. Fairbnb entered new agreements with municipalities to help relaunch tourism on a sustainable and transparent basis and many of our partners and colleagues mobilised their networks and resources to help their cities weather the crisis.

Many areas of our life have been immediately transformed by the COVID-19 crisis and we could only speculate on how these areas would change once the lockdown is over. While we were flooded with information about the numbers of infections and the security measures taken by governments, however, it was difficult to see among the white noise of information how life was changing in cities. And when borders closed and every country chose to fight the spread of the virus within its national boundaries, it was hard to find “Europe” in all this, and the mechanisms we had developed in Europe to exchange knowledge and learn from one another seemed to vanish overnight.

On 20 March we broadcasted the first edition of Cooperative City in Quarantine, a one-hour discussion livestreamed on Facebook with the aim of connecting urban practitioners in different cities and sharing their understanding of how the cities they lived in were transforming. The first event was nothing less than euphoric. Seeing our friends and colleagues in Lisbon, Madrid, Rome, Vienna and Budapest suddenly meant that we could forget about our isolation and hear first-hand information from other cities, some of them in the very epicentres of the pandemic’s outbreak. In this exchange, we heard about the emergence of new solidarity initiatives in Rome, including networks of food distribution, a hotline to help protecting workers’ rights, readings for children organised by bookshops, a movement of makers turning sub masks into components of ventilators for hospitals, fundraising activities by large foundations to create solidarity funds for the social sector, and the government-run Digital Solidarity platform, engaging companies to offer free digital services. From Lisbon we learned about the initiative Ninguém fica para trás, a national database of services offered to people in help, and from Madrid, about the Frena la Curva platform, operating in several Spanish-speaking countries, gathering information on tools to counteract exclusion and activating a number of Distributed Citizen Laboratories that promote experimentation, collaboration and citizens’ innovation under the conditions of Coronavirus emergency.

What emerged in front of our eyes was a test mode for another kind of city. As Bahanur Nasya, our colleague in Vienna eloquently said: “We all are experiencing how adaptation might look like in the future, how we potentially can limit our consumption, working hours, use of resources etc. In this regard the current situation is a training for future challenges.”

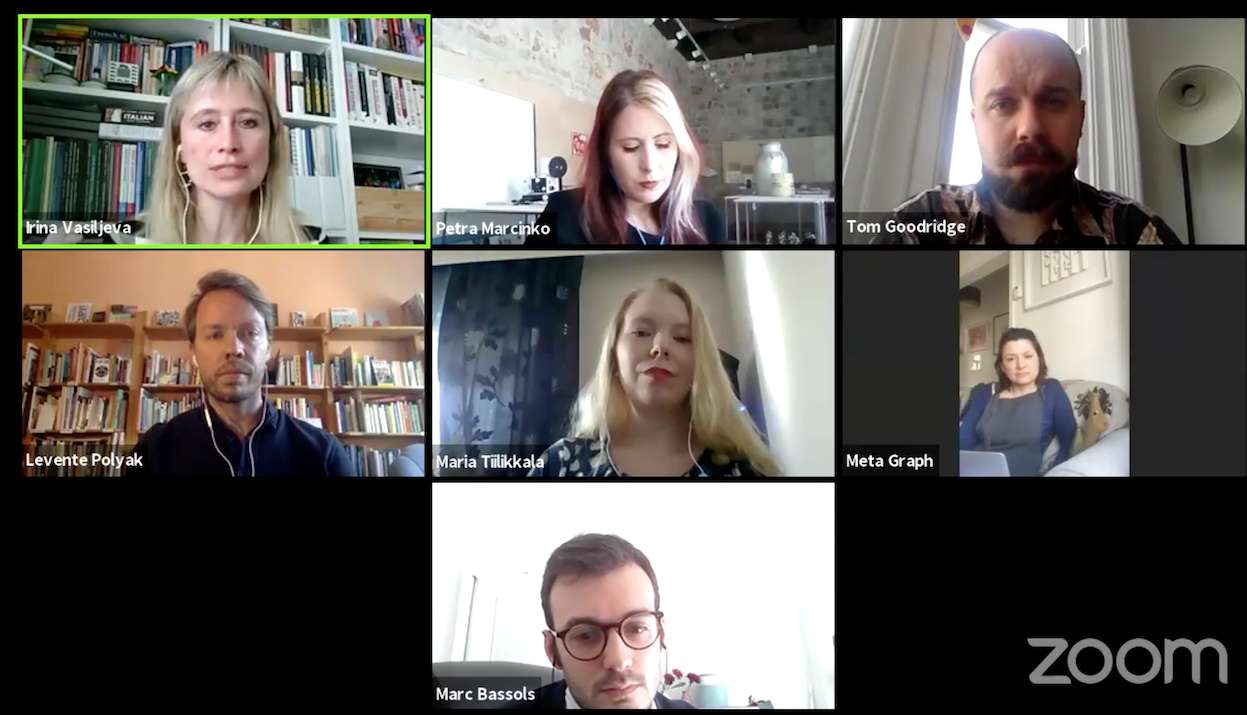

The success of the first event inspired us to engage in a series. Developing a webinar raised several challenges. We had to learn to use a platform (we chose Zoom) that allowed live streaming through social media platforms. This setup allowed us to have a closed discussion on Zoom (with no disturbances for the speakers) and an open public streaming on Facebook where the audience could comment and send questions to the speakers. We also created a workflow for each event that included a team to prepare the episodes and get in touch with the invited speakers, a host to moderate the discussion, a production manager to oversee the live streaming and another person to moderate the comments on the Facebook page and cluster the questions to be forwarded to the discussion host. Each video is later published on Cooperative City’s YouTube channel and summary articles are posted on the magazine’s website. Once this workflow was established, we could focus on the content of the events; in the following months of the lockdown we hosted a dozen events on the Cooperative City Facebook page.

In the 27 March episode on food, we learned how the crisis tested the food sovereignty of European cities and regions: while large supermarket chains failed to secure home delivery services, short chain distribution initiatives, based on direct contacts between producers and consumers experienced a boom during the lockdown. In Maribor, for instance, the municipality developed an app to enable direct purchase from local farms. In Rome, neighbourhood-scale food markets themselves had begun to organise home delivery to their clients. The arrival of the harvest season, however, all of a sudden revealed the dependence of agriculture on migrant labour.

In the 3 April episode on culture, we explored the situation of cultural workers and organisations. While cultural organisations immediately responded to the lockdown with presenting their archives, streaming their shows and moving many of their activities online, there has been little institutional support to help them weather the crisis. As many cultural workers are freelancers, they are often forgotten by both social security and official economic recovery packages, and need to rely on their own resources. Therefore, many cultural organisations have called for continuous support by their communities by organising fundraising campaigns and online events, as well as for rent freezes to reduce fixed costs for a period without revenues. Governments, municipalities, philanthropic foundations and crowdfunding platforms also launched a variety of initiatives, emergency and solidarity funds to save organisations from bankruptcy.

On 8 April, we welcomed partners of the ACTive NGOs URBACT network to share their experiences of the roles played by NGO Houses and their civic ecosystems in handling the COVID-19 crisis. Civic spaces are at the heart of local civil societies, offering venues for encounters, events and exchange; many of these activities have become impossible during this period of social distancing and lockdown. Therefore, many of these venues moved their activities online and often became protagonists in emerging solidarity networks. Community venues, understanding the needs of their communities, have quickly reacted both to the sanitary crisis and the lockdown, taking up tasks to address the mental well-being of communities in Riga, or to 3D-print facemasks in Dubrovnik. In many cases, while moving activities online was relatively smooth from the side of the organisations themselves, the digital gap created an important challenge on the side of their communities: many elderly users of Santa Pola’s community venues, for instance, or disadvantaged households in East Brighton have limited access to digital tools and internet.

On 17 April, we hosted a discussion about tourism. Tourism, among the most affected sectors of the economy, had already been seen as a major force transforming European cities before the current crisis before practically evaporating in March and April. Tourism businesses, representing up to 20% in European national economies, were among the first to close down because of the coronavirus: despite significant bailout packages by governments, many smaller businesses that have no financial reserves risk to close forever. The suspension of tourism has had positive impacts as well: on one hand, the arrival of many airbnb apartments to the long-term rental market might make housing more accessible and affordable even in former tourism hotspots. On the other hand, the shift from international travel to local tourism might benefit tourism businesses, hotels, hostels, restaurants or other service providers with stronger ties to their local communities. New concepts of tourism, such as promoted by the Fairbnb platform, can help cities transitioning towards a more sustainable form of tourism.

On 24 April, we talked about the commons. Defined as common goods, spaces, services and resources managed by communities have been particularly under pressure during the current lockdown. However, while many common spaces had to close due to safety regulations, their communities proved to be important protagonists of the solidarity movements across Europe. Some commons activities, like Nonna Roma has increased its regular food aid from 300 to over 2000 families. Others like Plateau Urbain turned their spaces into food distribution hubs. Some commons initiatives are developing spaces based on solidarity and shared responsibilities that seem better positioned to respond to the current crisis: “projects that are based on solidarity, mutual help and cooperation really make a difference and build stronger, more resilient communities,” claimed Joaquín de Santos, member of the Community Land Trust Bruxelles. As Ugo Mattei, the renown commons lawyer suggested, the commons movement has matured since the 2008 crisis and is ready to act as a driving force towards a more equal society: “In the next period when people lose their resources, commons initiatives might have an important role and thrive.”

In May, other episodes followed and we continued to address topics like labour, refugees, mobility and public spaces; issues we felt as central to understand the impact of COVID-19 on our future cities. With the proliferation of webinars, discussions and workshops across the web, the opening of the quarantine and the arrival of summer, we saw our slice of the internet’s attention reduced, but our message remained intact: to counter inward-looking policy solutions that address only national political constituents, there is more need for international cooperation now than ever. And to enable this, there is a need for platforms of knowledge exchange, such as Cooperative City and many others.

In a way, COVID-19 is a test for another future. The lockdown has forced many activities to catapult themselves in the future, by reinventing themselves in the digital realm or by getting organised around local, neighbourhood-scale networks. While the push towards digitalisation manifests itself most spectacularly in the field of education where millions of schoolkids were for the first time joining their classes online, it also accelerates the digitalisation process of many companies and non-profit organisations, including cultural venues and community spaces. In the meanwhile, as Angela Merkel also mentioned in her public address, neighbourhood solidarity networks have become crucial for maintaining key services and to take care of the most vulnerable members of communities. With all the destruction it makes across Europe and the world, COVID-19 forces us to rethink our structures of economy, consumption, mobility, tourism, social welfare and education, among many other fields.

Levente Polyak (Lead Expert of ACTive NGOs, co-founder of Eutropian and Cooperative City)

Submitted by z.biteniece on

Submitted by z.biteniece on