Analysis of the city centre: a good place to begin to understand pathways to revitalisation (Part 1)

Edited on

13 October 2017What actions will make our city centres more vibrant places? How do we make sure that our actions are also good for our local economy while sustaining social cohesion? Can our actions also lower carbon emissions? Will city centre improvements make our cities more endearing for residents?

The City Centre Doctor Project is a partnership of 10 small cities in Europe that appreciate the opportunity provided by the URBACT III Programme to grapple with these questions. The Project applies the ‘URBACT method’ to deepen an understanding of the main issues in the city centre through engagement with local stakeholders such as business groups including local retailers; social services; older residents living in the centre; and young people who play and maybe work in the centre.

All the partner cities established multi-stakeholder groups (i.e. URBACT Local Groups or ULGs), facilitated by their municipalities, to coordinate analysis of their city centres and to organise activities to co-create revitalisation ideas. These groups will likely continue after the Project with their city centre coordination role.

The ULGs have completed the place analysis stage of the Project. In each partner city, a survey was conducted with residents to determine their preferences as ‘users’ of the city centre. Interviews were organised and administered by the ULGs with a minimum target of 150 respondents per city. All cities managed to exceed the target (See table).

The ULGs have completed the place analysis stage of the Project. In each partner city, a survey was conducted with residents to determine their preferences as ‘users’ of the city centre. Interviews were organised and administered by the ULGs with a minimum target of 150 respondents per city. All cities managed to exceed the target (See table).

All ULGs were satisfied with a diverse profile of respondents regarding age, occupation and education as well as having a gender balance. Some cities such as Heerlen and San Dona di Piave used the opportunity to compare the survey results with previous studies of their cities. Some cities such as Petrinja, Valmez and Nort-sur-Erdre used the process for their ULGs to map a defined area as the agreed functional city centre.

At the end of January 2017 each partner city produced a place analysis report, which also included the use of tools such as PPS place observation sheets, a SWOT analysis by the ULG and where possible, the feedback from other cities during transnational visits using | Start | Stop | Continue | Improve | analysis. These reports allow us to make comparisons and attempt to draw inferences from data patterns in all ten cities.

Four specific themes are investigated namely:

• Mobility and perceptions of safety in the city centre

• Perceptions of the attractiveness of retail and leisure in the city centre

• The relative strength of the city centre as a destination for work and doing business

• Observations of the uses and quality of public spaces in the city centre.

Each theme will form the topic for an article. Herewith follows the first in a series of four articles.

Mobility and perceptions of safety in the city centre

Many cities are improving their city centres by actions to change car-centric behaviour of residents and especially by changing their streets from exclusively for car-use to a range of uses and activities including by creating cycle lanes, public transport lanes (trams, buses and taxis), larger pedestrian pavement areas, less on-street parking, more planting (trees and flower boxes) and new ambient LED lighting. The aim is to make the city centre more ‘walkable’ thus creating conditions for increasing footfall and extending the hours of activity in the centre, resulting in a net expansion of the customer base for city centre businesses. Will such changes be possible for partner cities in the project?

This will not only be a question of resources and budget, but also whether stakeholders will accept changes and if residents are ‘ready’ to change their own behaviour. Issues that ULGs should consider include levels of car dependency; resistance to ‘narrowing’ of streets and removing parking spaces; safety for cyclists; and the viability of public transport options.

The survey provides insights regarding mobility and safety aspects which partner cities should focus on to change perceptions. Amarante and Naas display a relative high car dependency with 69.5% and 59.3% of respondents respectively, primarily using the car to go to the city centre (Figure 1).

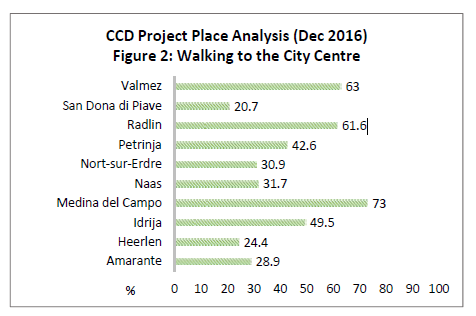

The city of Medina del Campo however is a more walkable city. In the survey 73% of residents indicated that they walk to the city centre (Figure 2) and only 18% use the car to go to the centre (Figure 1). In the cities of Nort-sur-Erdre, Naas and Amarante less than a third of residents surveyed walk to the city centre (Figure 2). The low levels of walking to the centre In Heerlen and San Dona di Piave is balanced by higher cycling levels.

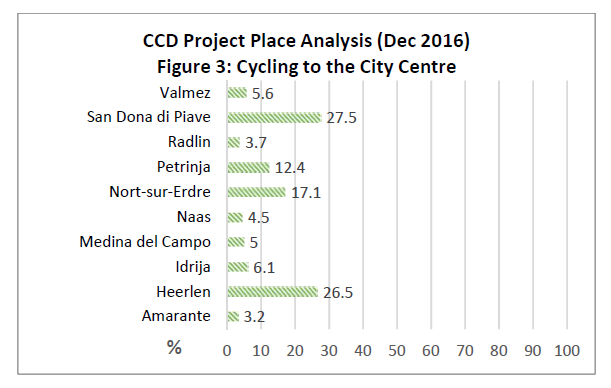

In most partner cities cycling to and in the city centre is at a very low base level. In Heerlen and San Dona di Piave cycling to the centre is an option used by at least one in every four residents (Figure 3).

In most partner cities cycling to and in the city centre is at a very low base level. In Heerlen and San Dona di Piave cycling to the centre is an option used by at least one in every four residents (Figure 3).

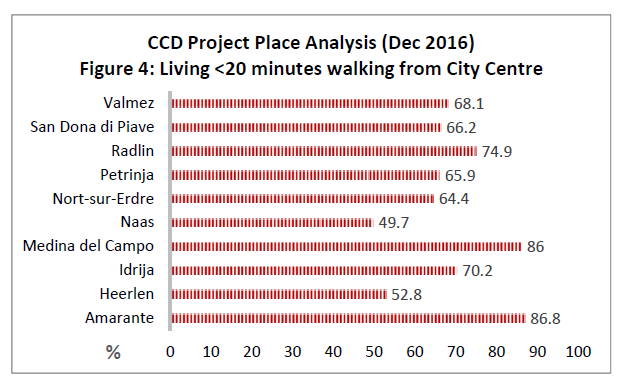

The question could be asked if the physical distances or terrain make it difficult for residents to cycle or walk to the centre. Only the cities of Amarante, Idrija and Petrinja are situated on hilly terrain with steep gradients that could deter cycling or walking to the centre. Except for Naas and Heerlen, most residents live in close proximity to the centre so that it will take them less than 20 minutes to walk to the centre (Figure 4).

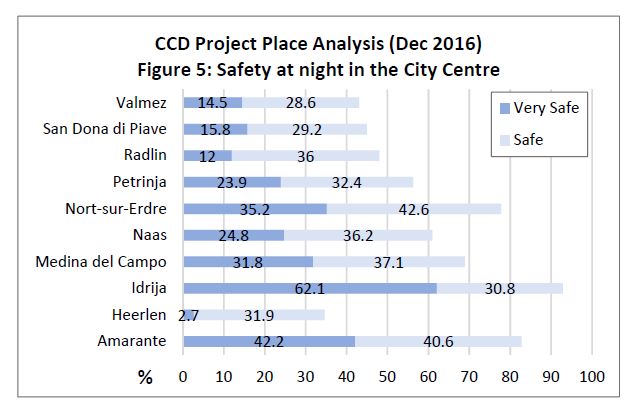

A perceived lack of safety in the city centre detracts from its appeal. The converse is also true. If a city is perceived to be safe, especially at night, then it has good potential to attract people to use the city centre.

In the cities of Valmez, San Dona di Piave, Radlin and Heerlen less than half of respondents perceived the city to be safe or very safe at night. Respondents in Idrija on the other hand gave an exceptionally high rating of their city centre as a safe place (Figure 5).

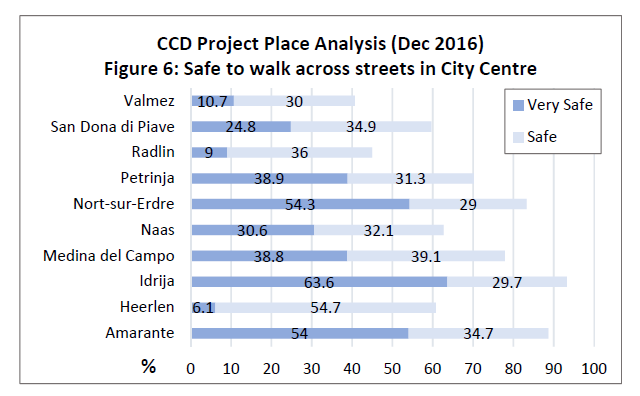

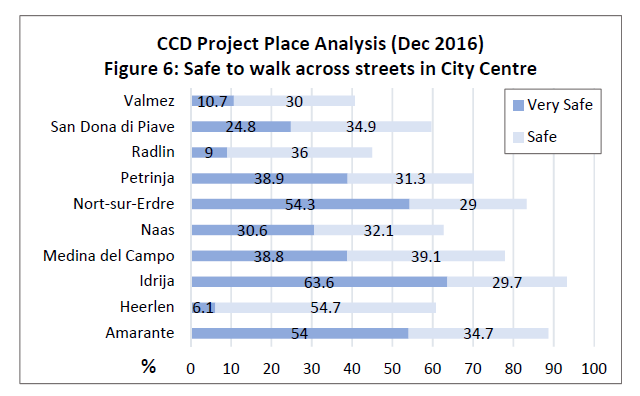

Respondents in most of the partner cities perceive it to be safe to walk across streets in the city centre. In Valmez and Radlin however less than half of the respondents rated the streets to be safe for walking (Figure 6). This relative lower rating reflects the specific traffic problems identified in these two cities namely large volumes of traffic with a high proportion of heavy vehicles regularly traversing the centre at specific times of the day and night.

Respondents in most of the partner cities perceive it to be safe to walk across streets in the city centre. In Valmez and Radlin however less than half of the respondents rated the streets to be safe for walking (Figure 6). This relative lower rating reflects the specific traffic problems identified in these two cities namely large volumes of traffic with a high proportion of heavy vehicles regularly traversing the centre at specific times of the day and night.

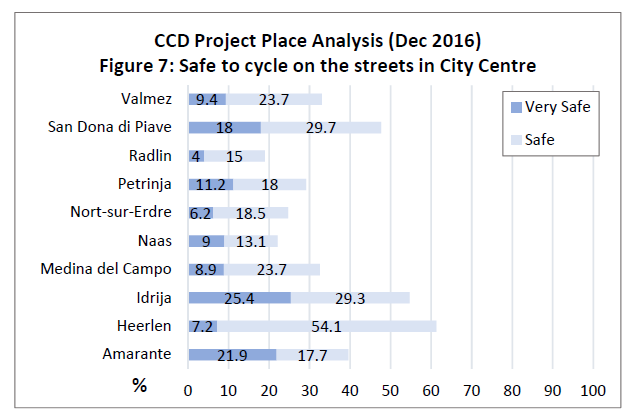

In most of the partner cities respondents perceive the city centre as not a safe place to cycle. The exceptions are the cities of Idrija and Heerlen where more than half of the respondents did rate their city centres as safe for cycling (Figure 7). The rating for safe cycling in the city centre of San Dona di Piave is also a positive affirmation for the recent initiatives of this city to create cycle lanes and limit car use in parts of the centre.

Conclusion

The survey gave the ULGs of the partner cities the opportunity to analyse issues of mobility and safety in their city centres based on the responses of a reasonably diverse sample of residents. The Project’s added value is that ULGs can also compare and benchmark against the responses in their project partner cities. The survey results also indicate which cities could be an example from which the other partner cities can learn.

Medina del Campo is clearly the partner city where residents have a ‘culture’ of walking to the city centre, while Heerlen is an example in the project where residents are also inclined to cycle to the city centre. San Dona di Piave is an example where recent actions to make the centre safer for cycling is showing positive results. Partner cities can learn from these cities how to improve mobility in their city centres. Similarly, Idrija has exceptional ratings for the safety of their city centre. The ULGs of partner cities can engage with their peers in Idrija to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that make the city centre so safe and what aspects could be designed as actions in their own city centres.

Medina del Campo is clearly the partner city where residents have a ‘culture’ of walking to the city centre, while Heerlen is an example in the project where residents are also inclined to cycle to the city centre. San Dona di Piave is an example where recent actions to make the centre safer for cycling is showing positive results. Partner cities can learn from these cities how to improve mobility in their city centres. Similarly, Idrija has exceptional ratings for the safety of their city centre. The ULGs of partner cities can engage with their peers in Idrija to gain a deeper understanding of the factors that make the city centre so safe and what aspects could be designed as actions in their own city centres.

Positive perceptions of mobility and safety in the city centre should contribute to the attractiveness of the city centre. These are aspects that each city can control and improve. In discussions about the place analysis results at the project’s transnational visit to

Amarante, several partners mentioned that the ratings on safety in the city centre were more positive than expected and that the number of residents living within 20 minutes walking distance from the centre were much higher than expected. If it is true that ‘what gets measured, gets done’, then hopefully the ULGs will use these insights to develop actions such as increased permeability, better lighting and more cycle lanes that will further improve mobility and safety in their city centres and thus contribute to revitalising their city centres.

The next theme to be examined using the survey results will be the relative attractiveness of retail and leisure in the city centres of the partner cities in the City Centre Doctor Project.

Submitted by Alberto Ferri on

Submitted by Alberto Ferri on